In late February, Captain Marvel was inundated with low ratings on the review-aggregation site Rotten Tomatoes. The movie, which had not yet been released, saw its “want to see score” fall to 28 percent. The reviews were mostly by people criticizing the fact that Marvel’s new superhero is a woman—a “review bomb” that started when the trailer was released in September. As a result, Rotten Tomatoes banned preemptive scoring.

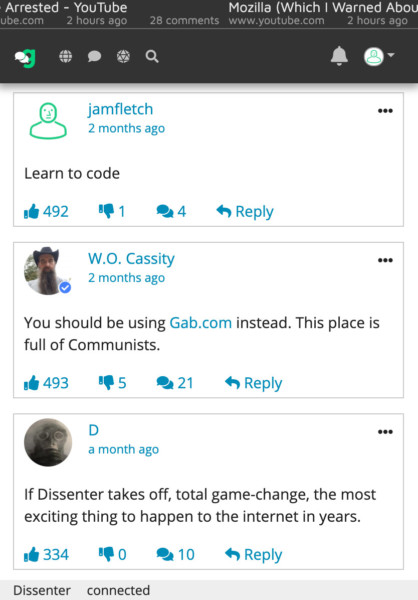

The reviewers soon migrated to another platform. Hundreds of sexist comments about Captain Marvel started to reappear, this time on a browser extension called Dissenter. The plugin, available on most web browsers, allows anyone to comment on any webpage on the internet—and to see the comments left by other Dissenter users. Without having the plugin installed, the comments are invisible.

ICYMI: The problem with Captain America’s new ‘both sides’ website

Dissenter acts as a workaround for people wishing to comment on websites, even those without a comment section. One user, Cody Jassman, describe the plugin as “like the graffiti painted in the alley on every web page. You can take a look around and see what passersby are saying.”

The plugin was launched in beta at the end of February by Andrew Torba, who co-founded Gab, a far-right social network. Gab is well known for being the platform where Robert Bowers, the suspected Pittsburgh synagogue shooter, published anti-Semitic comments before he allegedly killed 11 people and wounded many others at the Tree of Life synagogue.

Anti-Semitism, racism, and calls for violence lurk in the Dissenter comment feeds. To give a single example, on The Washington Post’s homepage, a user commented on Dissenter, “hang every employee at wapo for sedition, treason and crimes against humanity resulting in the mass murder of citizens around the world.” This comment was liked 27 times.

The plugin is already attracting a user base that mirrors Gab’s. The two are tied together sort of like Facebook and Facebook Messenger—if you have a Gab account, you can sign into Dissenter, and if you sign up for a Dissenter account, you’ll automatically be signed up for Gab, as well.

According to Torba, who CJR spoke with via email, since its beta launch, Dissenter registered 85,000 users who have made 500,000 comments on 71,000 domains. Captain Marvel’s Rotten Tomatoes page has been commented on more than 4,500 times. Twitter and Facebook have also garnered many comments from Dissenter users.

Dissenter recalls apps like Google Sidewiki (2009-2011), often cited as one of Google’s worst products. Hypothesis, an open-source note-taking add-on founded in 2011, allowed a group of climate scientists to annotate a Wall Street Journal editorial about climate change. The platform Genius, started in 2009 with a focus on hip-hop music, started a feature five years later that allows its users to annotate and interpret lyrics as well as news stories and other documents. Genius requires a website to opt in by putting a line of code in their site.

What is different, though, is that Dissenter benefits from Gab’s user base—one that says it is focused on free speech, but which often skews toward hatred.

Jessie Daniels, a Professor at CUNY’s Hunter College and an expert on internet manifestations of racism, says that Dissenter creates a workaround for efforts to curb harmful speech online, all under the notion of free speech that Gab encourages. “I predict it will only make things worse for people who use the Internet and want it to be civil, but it will be a boon for trolls, white nationalists and neo-Nazis,” she says.

Kevin Roose, a technology columnist for The New York Times, says that, while Dissenter claims to be a place for free speech, it actually has the opposite effect. “I think they stifle public discourse,” he says. “One of the reasons Gab has attracted people who get kicked off of other platforms is they allow them to harass and use hate speech against anyone.” On open or mainstream networks, he adds, hate speech has a chilling effect on other people’s free speech.

ICYMI: A survey identifies 3 new types of journalists. Which one are you?

Dissenter’s community guidelines state that the plugin “protect[s] the expression of any viewpoint that is protected by the First Amendment of the US Constitution,” thus excluding copyright infringement, illegal pornography, malicious defamation, spam, and true threats.

Legally, Dissenter has very little liability when it comes to moderating or removing content on its plugin because of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which provides that a website or publisher is not liable in civil matters for the actions of commenters who post things on things they host. Torba told CJR that Dissenter relies mainly on user reports when it comes to flagging speech that breaks the law.

“If no one who would “flag” a violation ever sees it, and the people who see it aren’t complaining, Gab could presumably take a pretty lax approach to how they police those categories,” says Tarleton Gillespie, an adjunct associate professor in the department of communication at Cornell University. The law applies even when it comes to threats of violence made by users.

Dissenter is available on some web browsers for the time being, though Torba thinks it likely that the plugin will be eventually blocked by extension stores. After CJR reached out to Mozilla, which runs the Firefox browser, it removed Dissenter from its extension store because of violations regarding its conditions of use prohibiting hate speech. A spokesperson from Mozilla tells CJR: “Mozilla does not endorse hate speech, and we do not permit our platforms to be used to promote such content.” Google also removed the plugin on the Chrome Web Store, following a request for comment by CJR. Microsoft and Apple did not immediately respond to requests.

Torba has plans to get around these blocks. “The next logical step for us is to fork either Brave or Chromium (two open-source browsers) and build our own browser that has this common extension built in and maybe it has ad-blocking built in and maybe it has tracking blocking built in,” he said in a video. In the meantime, Dissenter has launched a chat function, which will allow users to communicate with each other in real time on any website on the internet.

The Rotten Tomatoes incident is just the latest in a long string of websites—including social media sites and news outlets—that have shut down or limited commenting in an effort to stall trolling behavior. NPR removed the comment section from its website in 2016. Vice did the same not long after, followed by similar moves at The Atlantic. In February, YouTube announced it would ban comments on almost all videos featuring people under 18 to fight child abuse and online pedophilia.

After the Christchurch mosque shootings last month, there were renewed calls to crack down on hateful content online. Last week, Australia passed a law that will punish social media companies with huge fines and even jail for executives if they fail to rapidly remove “abhorrent violent material.” On Monday, the government of the United Kingdom issued a position paper that says the country would make internet companies legally responsible for unlawful content and material that is damaging to individuals or the country.

For Tori Ekstrand, an Assistant Professor at the UNC School of Media and Journalism, the Christchurch attack “raises a lot of questions about what we’re going to do to regulate these companies, and about whether it’s possible to carve out regulation that withstands constitutional tests.”

Torba, though, thinks little of the development of new laws since the attack. He says that these laws do not concern Dissenter, which has no intention to having offices outside the US. “I could care less about the authoritarian and dystopian ‘speech laws’ in foreign countries,” he says. He plans to educate foreign users on the usage of VPNs to bypass any potential blocks.

ICYMI: “Absolutely shocking”: Journalists on edge over proposed bill

Martin Goillandeau and Makana Eyre are the authors. Martin Goillandeau is a French reporter from Lille who just graduated from the Columbia Journalism School. Before coming to the US, he covered the 2017 French election as a student in Paris. Martin has also worked for several TV and radio outlets in his home country. Makana Eyre is an American reporter based in Paris, France. He is a graduate of the Columbia Journalism School, where he was a fellow at the Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism. Makana works as a freelance correspondent for the Haitian Times, covering the Haitian diaspora in Europe.