While covering a press conference held in Paris at the height of the Cold War in 1951, French journalist Gilles de la Rocque felt that something was off. He had expected hostility between the politicians in the room, which included the deputy foreign ministers of the US, Soviet Union, France, and Great Britain. But he was struck that even the Eastern and Western journalists there to cover the event didn’t say a word to one another. It was then that his grand and bizarre idea was born. La Rocque would devote the rest of his life to melting the ice between East and West by creating an annual gathering of international journalists.

On skis.

As an avid skier from Les Trois Vallees, de la Roque dreamed of uniting journalists from opposing nations by gathering them in the great outdoors to enjoy each other’s company without the pressures of deadlines, competition, and politics. There, he hoped, they would simply see each other as fellow human beings, devoid of the divisions their governments sought to exploit.

In 1955, with the Cold War at its coldest, La Rocque got 65 journalists from eight countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Italy, Luxemburg, Switzerland, West Germany and Yugoslavia) to the slopes of Méribel, France, to take part in the first conference of the Ski Club of International Journalists (SCIJ). In the ensuing 63 years, SCIJ has gathered journalists from around the world at a different ski site each winter. The annual conference, which costs attendees 300 euros for a week of skiing, onsite lodging, food, and tours, is attended by an average of 200 journalists, representing the United States, Spain, Argentina, Russia, Turkey, Israel, Morocco, nearly every country in Eastern and Western Europe, and many others. The destinations are just as diverse: in 2010, SCIJ met in Argentina; in 2012, Turkey; in 2016, Italy. (Disclosure: I attended my first SCIJ conference in Bulgaria this February.)

With US-Russia relations once again at the center of global headlines, the story of SCIJ is a reminder of the importance of solidarity among journalists. Today there are dozens of journalism conferences that bring together reporters from around the world, but SCIJ was one of the first of its kind. Even now its aim is rare: gathering journalists not for lectures and workshops, but to explore each other’s cultures and worldviews.

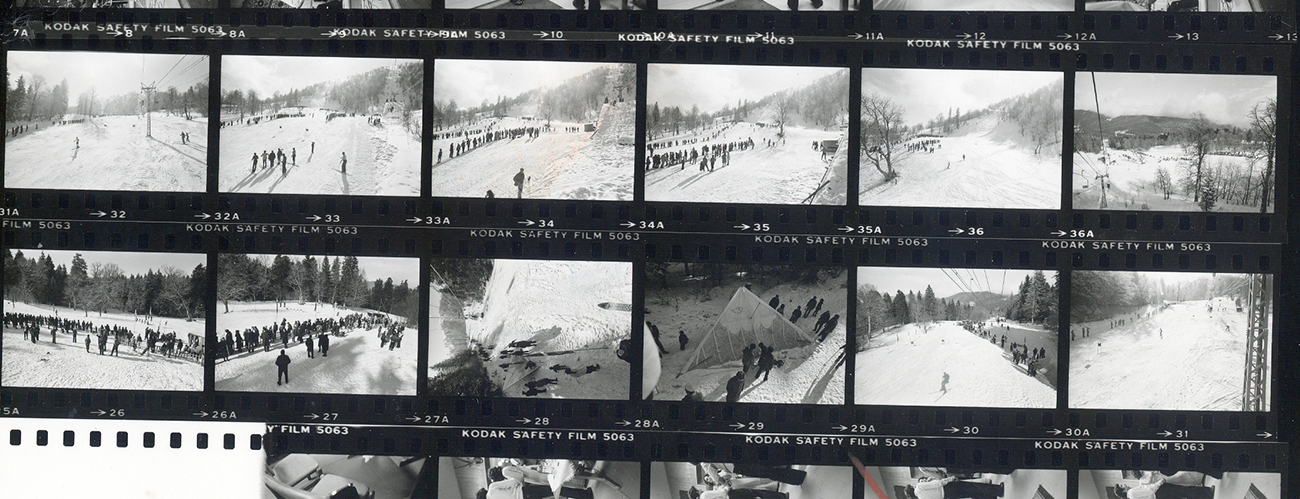

The first SCIJ conference, France, 1955. Photo courtesy SCIJ.

Gilles de la Rocque in the early days of SCIJ. Photo courtesy SCIJ.

Through all the years, just one SCIJ meeting took place in the Soviet Union. Veteran SCIJ members say this meeting was the fullest display of Gilles de la Rocque’s vision. His dream of breaking down barriers between East and West, they say, was realized here more than anywhere else.

In 1977, 22 years after the first SCIJ conference, 200 journalists from 32 countries met in Georgia. The event was closely coordinated with the KGB, says Nikolai Popov, a 79-year-old Russian journalist who joined SCIJ that year. “During Soviet times, the Russian SCIJ members were not only in touch with Kremlin officials,” he says, “the teams were headed by Kremlin officials who reported to their superiors.” In the early days of SCIJ, the Soviet reporters participated less to develop journalistic camaraderie than to gather intelligence and spread Communist ideology, says Popov, a Moscow native. After returning from SCIJ conferences overseas, he says, Soviet members “completed official reports on how successful the meeting was in terms of ideological yield—who is there ‘for us’ and who is ‘against.’”

The 1977 conference marked a shift among the Soviet membership. The meeting proved to be a great success, but it was almost a disaster. In a move indicative of international relations at the time, Soviet authorities banned Israeli journalists from the event. (The Soviet Union had backed Arab states in their wars with Israel.) In an early demonstration of the power of international journalistic solidarity, Soviet members of SCIJ rallied in support of their Israeli colleagues and managed to persuade the Kremlin to let the Israelis in.

Another hiccup came at the event itself, when one attendee nearly landed in a Soviet prison. British journalist Harry Stone arrived from London without his Soviet visa, which he had misplaced on his way to Leningrad. “In the USSR,” Popov says, arriving without a visa “was easily seen as an attempt at espionage or sabotage.” Left in the border zone without documents, Stone feared he would be taken to the Gulag. When Soviet officers brought him to a barracks-like hotel, he was absolutely sure of it. Eight hours later, after a full night of negotiations with authorities, Soviet members of SCIJ managed to secure Stone’s release and get him a new visa.

The conference was also full of memorable Communist-era details. For example, on their way to the slopes in Georgia, journalists were brought to Lenin’s mausoleum in Moscow. “Never, ever, before or later,” says Popov, “had foreign journalists in such numbers lined up to see the mummy of a man who eliminated the freedom of the press in his country.” The Georgian ski “resort” of Bakuriani, where the trip was based, had just one bathroom—an outhouse that clung to a cliff. The ski lifts were built in 1934, and dripped grease on skiers’ heads, leading some to use umbrellas on their way up the mountain.

Alexander Pumpyanskiy, the 77-year-old president of the Russian SCIJ team, is among the few remaining club members to have met La Rocque, who died in 2001. Pumpyanskiy’s 1978 interview with the SCIJ founder was published in The New Times, the Russian magazine where Pumpyanskiy served as editor in chief for 15 years. Pumpyanskiy now writes for the Novaya Gazeta, the country’s main opposition paper. Asked why he believed that skiing, of all things, could unite Eastern and Western journalists, La Rocque told Pumpyanskiy, “The mountains bring people together. In the mountains, a person remains alone with the sun, the sky, the clouds, and the wind blows away all sorts of nonsense.” Yet, La Rocque told Pumpyanskiy, he never dreamed his idea would be taken seriously. “It’s some kind of Boy Scout idea,” La Rocque recalled thinking. “It’s unlikely that serious people will like it.”

In Pumpyanskiy’s view, La Rocque’s pipe dream actually worked. “SCIJ provided a great freedom,” the Russian journalist tells me. “It freed the consciousness of my colleagues, of myself, and of very many people.”

These rare encounters with the other side were illuminating to Western journalists as well. “That was the first time I met people from behind the Iron Curtain, and it wasn’t because I hadn’t traveled,” says British journalist Michael Prowse of his first SCIJ conference in 1988. Prowse, who recently retired after 30 years at The Telegraph and The Times of London, had traveled extensively throughout Europe. Yet he had never spoken to anyone from the East. “It was a real eye-opener to hear firsthand from journalists, to find out what was really going on in their countries, and learn how much we were reading in Western journalism was true, and what was propaganda.”

In an age when journalists separated by international borders and warring governments can instantly connect online, it’s a wonder that SCIJ survives. The reason it does, says Prowse, SCIJ’s secretary general, is that nothing even close to it exists. “There are no models,” he says. “I went to open a bank account for SCIJ, and they had all these questions like, ‘What do you mean your members are from 40 different countries?’ You’ve got professional groups for journalists with special interests, but they don’t tend to be international. So there’s this understanding among members that this is a precious organization, and I think that’s why it’s survived all these years. People appreciate it.”

Given the recent revival of US–Russia tensions, holding a ski conference to bridge the divide between East and West may now seem passé, but members of SCIJ believe it still resonates. Peter Daalder, a Dutch journalist who joined SCIJ in 1987, says that today the club offers a rare inside understanding of political developments across the globe—for example, the right-wing nativist movements taking hold of his and other Western European nations. “To understand what’s going on,” he says, “you have to talk to people who are digging into these subjects every day.” Daalder says his connections with SCIJ members in foreign countries have frequently helped him access on-the-ground-sources for otherwise impenetrable stories.

For American journalists who feel persecuted in America’s political climate, particularly by President Trump’s verbal attacks against the media, the group provides some useful perspective.

“We have it a lot better,” says Risa Wyatt, a freelance journalist who heads SCIJ’s US team. Turkish members risk being jailed by their government if they publish negative stories, and Eastern European members have seen their colleagues murdered over their investigative work. But, she says, while speaking to journalists in countries with repressive media environments helps put the American situation in perspective, it also serves as a form of caution. “We have to make sure that we don’t end up under the constraints that these other journalist have to work under. We have to be vigilant that our freedoms are not attacked.”

Yardena Schwartz is a freelance journalist and Emmy-nominated producer based in Tel Aviv. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Time, Foreign Policy, Haaretz, The Jerusalem Post, CBS News, NBC News, and MSNBC. Previously, Yardena was a producer at NBC News in New York.