CAIRO—In the last decade, gender rights advocates have, to notable success, made the argument that welcoming women into workforces and economic markets is simply logical policy.

“In the 1970s and 1980s,” wrote Adam Segal in his book Advantage, “underrepresentation was considered primarily a social or moral issue—a question of affirmative action. Today, it is also seen as a competitiveness issue. Only by tapping into emerging demographics” will countries be able to maximize their output.

“Until the last few years,” according to Maddy Dychtwald and Christine Larson in their book Influence: How Women’s Soaring Economic Power Will Transform Our World for the Better, “the massive entry of women into the paid workforce seemed important mostly because it was a victory for social justice. Only recently has another more significant implication of women’s success become clear: The health of the global economy now demands that women realize their full potential as economic participants.”

The argument that including women makes organizations more economically vibrant hasn’t, however, been tapped to make the case for greater gender parity in journalism throughout the world. Gender diversity in newsrooms has been an area of concern in some countries for several decades, but the argument that gender parity strengthens a news outlet’s economic competitiveness is infrequently advanced.

A new report (pdf) of stunning depth released by The International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF) provides compelling evidence of the underrepresentation of women in journalism throughout the world. It assesses gender disparity at 522 media companies in 59 countries, finding that men occupy two-thirds of all full time positions. Eighty-two percent of full time employees at South Korean news organizations are men, as are just under 70 percent in Argentina and nearly 60 percent in Spain.

The 400-page report, though, mainly uses the moral approach to argue that greater female representation in journalism is important, rather than pointing out that news organizations that hire women are in a better position to compete. Wagging fingers at discrimination is less effective than making the case that equality increases earning power. “Moving people requires a price,” Eduardo Porter wrote in The Price of Everything.

The IWMF report does repeatedly make the case that female economic empowerment is important to overall development, but the economic benefits of employing more female newsmakers—both to news outlets and the news consuming public—aren’t emphasized in the report.

Gender equality within U.S. news organizations has rightly been a focus for decades, and many books and juried journal articles have been devoted to the topic. And since the 1970s, female students have outnumbered males in journalism programs at U.S. universities. Again, though, only recently have American news outlets begun to think more about gender as an economic force. Website sections like the St. Petersburg Times’s GoMomma, the Raleigh News & Observer’s TriangleMom2Mom, and The Arizona Republic’s MomsLikeMe, for example, have been rolled out only in the last few years.

Women are controlling greater portions of global wealth and independently making purchasing decisions. There’s no reason to believe that they won’t also increasingly determine core news organizations in countries throughout the world. Female literacy rates continue to approach male levels in developing markets, empowering millions of women to consume news through means other than TV and radio.

Women don’t represent a niche market, argue Dychtwald and Larson: “Women are the market.”

Only news organizations with the right mix of male and female newsmakers are likely to provide audiences the most complete economic picture, and such a picture will lead female (as well as male) spenders and investors to make better financial decisions.

Journalists guard the public purse, and women look out for other women. And money spared from corruption and waste is generally put to better use by women than men. This is true in both developed countries as well as emerging markets. “Women are more likely to enroll in defined contribution retirement plans and make larger contributions than men,” Dychtwald and Larson wrote. “And they’re more likely to buy and hold investments, rather than churn them.”

In developing countries, too, money that finds its way to women’s hands is better utilized. “[T]he [world’s] poorest families spend about 20 percent of incomes — 10 times as much as on education — on a combination of alcohol, tobacco, prostitution, sugary drinks and candy, and extravagant festivals,” Nicholas Kristof wrote in 2010. “And evidence is very strong, across a range of cultures, that this is largely because the purse strings are controlled by men. When women control the purse strings, money seems more likely to be spent on educating kids and starting businesses.”

In some cases, gender disparity in media is a matter of differing interests in politics and history, of course, not necessarily discrimination. Eighty-seven percent of writers that elect to contribute to Wikipedia are men, according to a January installment of NPR’s On the Media. That personal interests alone explain men outnumbering women 4-to-1 at South Korean news organizations, however, doesn’t seem to hold up.

A number of important economic markets stand out in the IWMF report on gender imbalance in journalism.

In Japan, the disparity is astonishing. While Japanese women have a near-100 percent literacy rate, almost 85 percent of full time journalism employees in Japan are men. The highest levels of news management practically exclude women outright, as Japanese men occupy 98.6 percent of jobs. Japan’s economy is weak, and the country has little room for major industries shutting out women’s talents.

India doesn’t fare any better. While more women in India hold top management positions in journalism than in Japan, they hold just 12 percent of all full time media jobs. India is a country with a history of official corruption and is a nation fighting its way out of poverty. But to do so, it will need more gender parity among its watchdogs.

Not all countries in the IWMF study, though, are underutilizing female journalists. Women in South Africa, for example, hold a slim majority of all full time journalism jobs. The country may have recently gained glory for hosting an all-male World Cup, but women in South Africa hold around 75 percent of senior-level management slots in the news business.

While gender parity may not be as economically consequential for Men’s Health and GQ magazines as it is for GlobalPost and The Times of India, journalism is generally no different from other businesses that are bolstered by fully utilizing female skills and ideas. “[T]here is ample hard evidence to show that tapping women’s talents, in every sphere, will make the world more equitable and more prosperous,” Dychtwald and Larson wrote.

Shut out half the sky and you don’t have as much commerce in the sunshine.

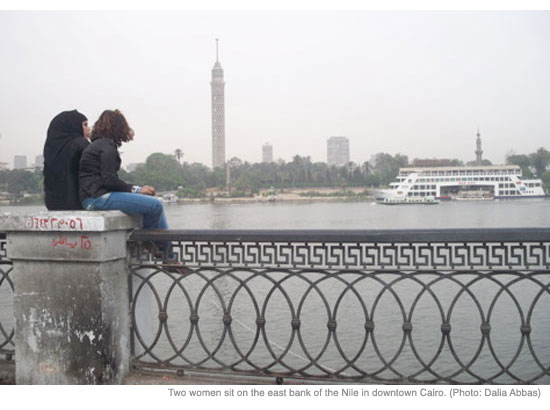

Justin D. Martin and Dalia Abbas collaborated on this article. Martin is a columnist for CJR and a journalism professor at The American University in Cairo. Abbas studies political science and history at the same university.