Scott Clement didn’t believe it. In the midst of the government shutdown last year, the Washington Post polling analyst learned news that Senator Ted Cruz, the Texas Republican spearheading the GOP’s push to defund Obamacare, cited a self-commissioned poll to argue that the fight in Congress actually boosted his party’s position.

That wasn’t quite what Clement and The Post’s polling team found after conducting three surveys before and during the 16-day government shutdown. Their findings: Americans overwhelmingly disapproved of the way the GOP was handling the situation, more so as it continued. A spate of polls by other media outlets found similar results.

“The purpose of the poll is to bring high-quality data to really fractious political debates,” Clement said, adding that The Post has conducted 25 polls so far this year. “When we get those results back we want to blare them through a loudspeaker. Part of why we cite our own polls so much is that we know the qualities of these the best.”

News organizations didn’t give much weight to Cruz’s poll, not only because of its source, but also because the balance of data pointed to a different conclusion. But when reporters cover polls by their own news organization, they often rely on a single survey. If the results are surprising, trend-hungry journalists served up just a few points of data are eager to cover the twist, even if it leaves audiences without the full picture. And that decision is all the more consequential as media outlets cover the last stretch of campaigning before the elections in early November.

“The outlier is always the story,” said Mark Blumenthal, senior polling editor at the Huffington Post and founding editor of Pollster.com. “If there are 10 polls, and all but one of them show similar results, that last one will be the story. It’s a big headline. We give it far more attention, rather than the opposite.”

They do this even though it doesn’t make statistical sense. Nine polls with boring but similar results typically provide a more reliable takeaway than one with surprising data. But media outlets surely have a marketing incentive to cover their own polls with the voice of God, giving them more weight in coverage than competing surveys or polling averages. With the rise of polling virtuosos like Nate Silver and aggregators like Real Clear Politics, though, journalists have no excuse to overlook the trend lines in favor of headlines.

“In general, more polling is better,” said Robert Y. Shapiro, a political science professor at Columbia University. “The more results you have, the more you get to see the common tendencies.”

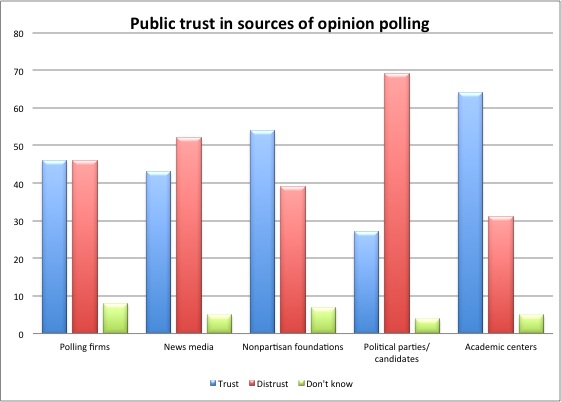

Poll of polls Source: Kantar US Insights

Poll of polls Source: Kantar US Insights

Nowhere is the inherent friction more evident than at metropolitan news organizations. Whereas national or niche outlets employ specialists who can consult on poll coverage or even conduct it themselves, their local counterparts don’t often have that luxury.

Decades ago, in-house polling arms were common, and “the accepted practice was to treat your poll as if it was the only measure, because it was your brand,” Blumenthal said. The subsequent rise of commercial polling firms, coupled with the news industry’s financial woes, rendered those operations expendable. Local media outlets today contract just a few polls each election season — if that — though they often still cover them as the only numbers that matter.

In mid-September, a Chicago Tribune poll found Democratic Gov. Pat Quinn held an 11-point edge over GOP challenger Bruce Rauner. Reporter Rick Pearson broke down the survey in a 1,600-word story that led the front page of the paper’s Sept. 14 print edition. Rauner had led in each of the five previous polls since his March primary victory, and the Real Clear Politics polling average pegs Quinn’s advantage at a mere 1.5 percentage points — practically nothing. Yet neither of those facts, let alone the results from previous polls, was mentioned in the piece. Pearson did not respond to a request for comment, and Political Editor Eric Krol declined to be interviewed for this piece.

Some news outlets indeed acknowledge that their polls might be outliers compared to the overall trend. Still, they could do more to temper their presentation of such numbers. In Kentucky, home to a closely watched Senate race between Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell and Democratic challenger Alison Lundergan Grimes, a poll this week co-sponsored by The Courier-Journal, Lexington Herald-Leader, WHAS-TV, and WKYT-TV made for loud headlines. “Grimes surges ahead of McConnell in poll,” The Courier-Journal’s blared. “Grimes rebounds, takes two-point lead over McConnell” the Herald-Leader’s chimed in. WKYT’s Web story described a “surge of popularity,” while WHAS reported, “The pendulum that had been swinging toward Republican Mitch McConnell in Kentucky’s U.S. Senate race has reversed direction.” Not one, however, said that FiveThirtyEight.com and The New York Times’ Upshot give McConnell 77 percent and 86 percent chances of winning, respectively.

Some news outlets indeed acknowledge that their polls might be outliers compared to the overall trend. Still, they could do more to temper their presentation of such numbers. In Kentucky, home to a closely watched Senate race between Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell and Democratic challenger Alison Lundergan Grimes, a poll this week co-sponsored by The Courier-Journal, Lexington Herald-Leader, WHAS-TV, and WKYT-TV made for loud headlines. “Grimes surges ahead of McConnell in poll,” The Courier-Journal’s blared. “Grimes rebounds, takes two-point lead over McConnell” the Herald-Leader’s chimed in. WKYT’s Web story described a “surge of popularity,” while WHAS reported, “The pendulum that had been swinging toward Republican Mitch McConnell in Kentucky’s U.S. Senate race has reversed direction.” Not one, however, said that FiveThirtyEight.com and The New York Times’ Upshot give McConnell 77 percent and 86 percent chances of winning, respectively.

Susan Pinkus spent more than a decade at the helm of the Los Angeles Times’ in-house polling department, which fell victim to budget cuts after the 2008 presidential election. She worked with reporters to hone surveys corresponding with major news events, held polling workshops, and even edited stories before they went to print. The most common pitfall of journalists covering polls, she said, was to make something out of nothing.

“Polling is not a predictor of the future — it’s just what we’re polling at that particular moment in time,” Pinkus said by phone. She added later, “Reporters and readers want to know who’s ahead and who’s winning. But that’s not how it works, especially in close polls.”

David Uberti is a writer in New York. He was previously a media reporter for Gizmodo Media Group and a staff writer for CJR. Follow him on Twitter @DavidUberti.