North Korean dictator Kim Jong-il has died. A couple of days, perhaps, after the Dear Leader passed, the state news agency informed the people, citing Kim’s “overwork” on behalf of North Koreans and related “mental and physical strain.”

Strain at least some of which can be attributed to the work required to maintain the country’s standing, for some ten years running, at last or second-to-last on Reporters Without Borders’s World Press Freedom Index.

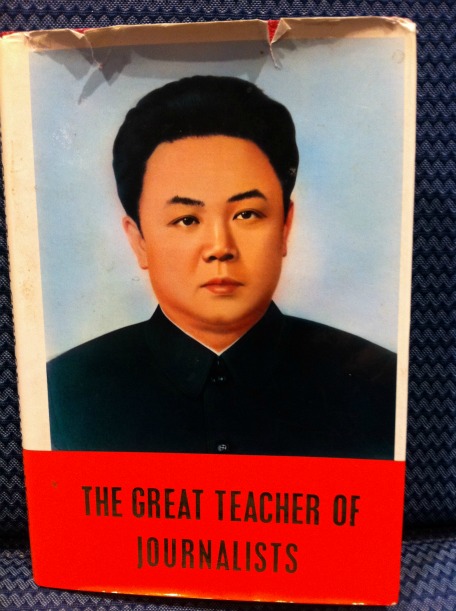

That work—the tireless editing, troubleshooting and caretaking of his country’s media workers— is painstakingly documented in a 170-page book, The Great Teacher of Journalists, published in Pyongyang in 1983 (eleven years before Kim succeeded his father) in English by the DPRK’s Foreign Languages Publishing House. (Get your copy at Amazon for $24.50). Imagine the strain of “plac[ing] the pressman at the zenith of happiness and glory”—it’s in the book!—of “constantly giving them meticulous guidance in spite of the heavy pressure of the task of leading the revolution and construction.”

Indeed, the book confirms, “the annals of the care with which the dear leader Comrade Kim Jong Il has guided and looked after the men of the press are replete with moving stories,” like that time he sent wedding gifts to a newspaper editor, unexpectedly showed up at the marriage party, and refused a cushion to sit on. Or, when, “having read the first galley proof [of a newspaper piece], the dear leader clearly showed how to correct the article,” by re-focusing the piece “on the noble personality of the great leader.” Or, that one time he “corrected” something in a reporter’s notebook. Or how, (and, this is a chapter title), “A Reporter [Was] Saved Miraculously from the Jaws of Death”—by Kim Jong-il.

Can you say the same for your editor? (Mine merely handed me a copy of this book and told me to “write something” about it right away. No “meticulous guidance” on the proper tone for a piece about a red-covered book of propaganda produced to bolster a Dear Leader’s inevitable inheritance of power from a Great Leader, which later came to pass, along with widespread famine and the detonation of two nuclear devices — with the news hook being said Leader’s death, possibly of a heart attack. Light tone, then?)

Well, what might we learn from the Dear Editor? And, was he really so very different from yours or mine?

Selected Journalism Counsel from Kim Jong-il

No one reads long

Thanks to the Dear Leader’s stewardship, “writings in the Party paper have also been put on the right track,” in that “in the past they were long with a poor content, but now they’re short and contain rich material.”

(And yet, this is from the same Editor who, readers are later told, once changed a newspaper headline from “Love is Like the Sunshine” to “Noble Love that Made a Longstanding Intellectual’s Life Brilliant,” sub-hed, “An account of the Great Leader Training Comrade Kang Young Change into Revolutionized Intellectual, a Leadership Official of the Country.”)

On puff pieces

“Giving prominence to these typical men is an effective method of imbuing people with loyalty to the Party and the leader,” Kim Jong-il explained.

On dressing the part

Kim Jong-il questioned why “telecasters in Korean attire appear in the programmes for coal miners,” advising that telecasters “should wear Korean dresses in the news hour, but they had better put on simple dresses and act like agitators when encouraging people to increased production.” In short, they should be “dressing themselves to suit the programmes and circumstances.” (Remember this, Matt Lauer, next time you reach for the Wayfarers while reporting on a college student’s murder trial appeal).

On not boring viewers

His instruction “brought about a new change in the standpoint, posture, ideological viewpoint and way of thinking of the announcers who speak to the public through microphones” (which, we have a few of those folks stateside, too). Specifically: “Inanimate, inert and dull speech would be unable to rouse people vigorously to the revolutionary struggle and the work of constriction… Announcers’ voice itself must give an impulse to rush forward.” (Lean forward?)

On reading up

“Journalists must read books more than anyone else and make study their regular habit.” (So far, so good). “In particular, you must profoundly study the leader’s works and thus acquaint yourselves thoroughly with their content. Only then will you be able to successfully carry out information activities in accordance with the leader’s thoughts and intentions.”

On shoe leather

“Comrade journalist, you must see things on the spot before you write your articles. Otherwise you may talk big,” advised the Dear Leader astutely, in one chapter. This anecdote, perhaps the most relatable in the book, continues:

At the moment the journalist blushed. Across his mind flashed the bygones when he used to write his articles in his office only after his conversation with the officials…He gave no thought to taking the trouble of traveling more than sixteen kilometres across the flooded river to visit this rugged place [and count for himself the pepper bushes which the government was touting as part of a successful planting of oil-bearing trees].

Turns out, there weren’t very many pepper bushes growing there at all. “The dear leader told the man that he better not report about the pepper bushes at the moment but introduce them later when more oil-bearing trees would have been planted.” So, go see things “on the spot” but if what is there is not as lush it was billed, you’ll know it is not the right time to introduce your report.

For news photographers

“In fixing the place of the camera, the cameraman’s first consideration should be how to take the leader’s best picture.” Also: “Press the shutter when you are sure of success.”

For TV news producers

“Unlike the cinema, the TV has a small screen. Therefore, you should close up the object, and should not make it small. In particular, this is all the more so when you show men. Only then will one take interest in looking into the TV screen.”

For print reporters

“An article should not be monotonous and stiff but woven with concrete facts so that the readers could read it with interest.”

And: “You seem to go into detail when collecting the materials. That’s a good thing. But you should not leave the great leader when you cover functions held in his presence. Only then will you be able to impressively cover his on-the-spot guidance, and also write good articles.”

In one anecdote, Kim Jong-il offers a new, more constructive mindset with which to regard one’s barely recognizable story, blighted and blemished by an editor’s heavy hand (emphasis mine):

The dear leader Comrade Kim Jong Il, in spite of the pressure of the Party and state affairs, went over and over again a political essay written by journalists of the Party paper, until it became perfect.

The writers were deeply moved by the great efforts he had made and the meticulous care he had taken of the political essay, when they saw his benevolent pen marks as they received the first proof he had checked.

Turning over page by page with gratitude, the writers could see at a glance that he had read and revised the essay several times. It was because the paper bore distinctive ball-pen marks of different colours, red, black, and blue, which he had left while revising and underlining whenever necessary.

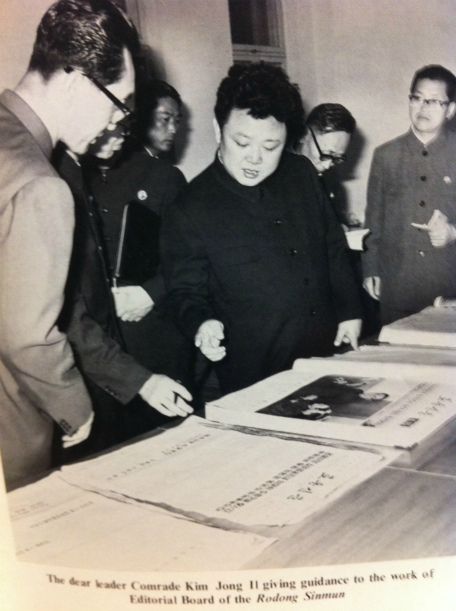

If, for you, seeing is believing, at the front of The Great Teacher of Journalists, there are four black-and-white images of Kim Jong-il performing the exhausting, benevolent work of the Dear Editor. And, in all of the images, he is looking at things.