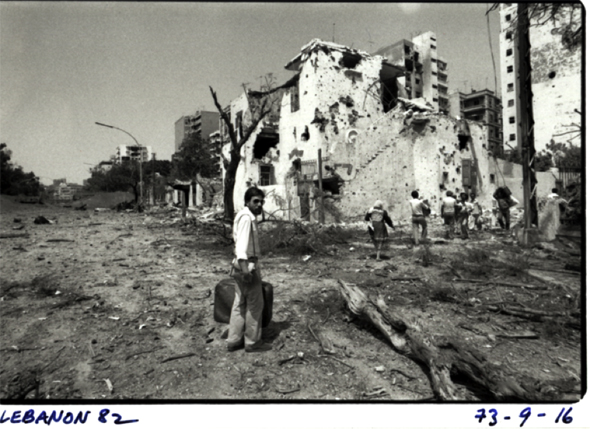

Borderland The author entering West Beirut, 1982 (David Turnley)

This story is being co-published by CJR and by The Big Roundtable, a new digital home for narrative journalism.

Bright, bright light. So bright it blinds me. The man with the rifle, who is about to kill me, has me standing up against the wall. I can’t stop fixating on the light. I can’t do anything. Can’t bend. Can’t run. Can’t do anything.

So this is how it ends? Strange. I am young. Shouldn’t I have more time?

It’s not the burning yellow sunlight, but an intense white light that distracts me most as I wait here on this miserable, stinking, war-pocked street of bombed-out buildings in bombed-out West Beirut.

I’m the afternoon show for a crowd of people waiting to see somebody beside themselves get blown away.

I wait here just up the hill from a pile of rotting food and garbage, standing next to a partially collapsed, bullet-riddled wall. Waiting my turn.

My suitcase is at my side, where I dropped it in the dirt. I am facing a short, plump, balding gunman in need of a shave. He is pointing a high-powered rifle at my chest.

I guess I’ll die soon. Bullets. I’ll tumble backwards. Maybe forwards. Who knows. I’ve never done this before. When it’s over, I imagine that they will leave me here with the rest of the blood-splashed vestiges of war that fill this part of Beirut.

It is another gate to hell here: the last checkpoint on the way in or out of besieged, maddened, and desperate West Beirut. I am a reporter. It is August 1982.

The day I arrived, a middle-aged Lebanese man told me of seeing a man run out into the street after an Israeli bombing attack hit his house and killed a member of his family. The man slit the throat of the first person who passed by–an Arab, it turned out, just like the enraged man, an Arab trapped in the vise of war. “He was crazy from the war,” the Lebanese man said. “War is crazy. Be careful.”

I try to seem calm. But I feel a shiver, and the scene in front of me is fading out quickly because I am fixating on the white light coming from nowhere and everywhere.

It floods out the callous jerk in the camouflage military jacket facing me. The more I focus on it, the more buttons and wheels shut down in my head.

Click. Reason.

Click. Strategy.

Click.

As the wheels turn off, I feel like I am in a swoon. I am not sweating. I seem to be breathing regularly. A few nights ago, when the fighting in the street got really violent here, I had trouble catching my breath in the basement of the low-budget hotel where I and a few other journalists were waiting it out. But I am not struggling to breathe now, and I am not shaking either. I’m glad for that.

I had faced a situation like this before, at a Syrian border checkpoint not long ago. My body shook so much then, despite my desperate efforts to stop it. The soldiers insisted we were Israelis, or that we were working with the Israelis, because our passports didn’t show how we had entered Jordan on the way to Syria. We had, in fact, come from Israel. But foolishly we–myself and two colleagues–had no idea that the lack of an entry stamp to Jordan would make us suspect.

Naïve journalists. First-timers to war.

On that day, I remember looking outside and seeing a bus whose markings showed it was bound for Istanbul. I fantasized about leaping through the window, rushing to the bus and yelling in Turkish for them to save me. My Turkish was so good then, from my days as a US Peace Corps volunteer there, that the escape plan came almost naturally to me. Ultimately, hours later, the Syrians walked us to the border and drew the narrow, wooden gate down behind us. In the total darkness, they ordered us to walk back to Jordan.

Hours after that all-night confrontation with Syrian soldiers, I could not shake the feeling of being and acting so vulnerable. I was horribly ashamed of my fear, and worse, realizing that I had been out of control.

But for all the hours I cowered before the bluffing bullies, for all the time we stood there in that small room with only a single window, our faces lit by a naked light bulb while young soldiers shook their guns in our faces–for all that, the Syrians never said they wished to kill us, not like the gunman now says he wants to do to me.

I am tired and hungry. I barely talk to anyone. …I am living in my shadow.

While I have time, I am silently saying goodbye to my wife, Suzanne, and my young son, Noah, and my daughter, Leyla. They are standing off somewhat in the distance and smiling back at me. It seems almost as if they are posed for a warm, cheery photograph that will be framed for a living-room table: heads tilted slightly, all of them neatly dressed. And yet they can’t hear me as I speak to them. They are back in Detroit where it’s safe.

Goodbye. So long. Please take care. Love you always. Love you a lot. Help Mom. See ya. Love you all.

But then I can barely make them out, because the white light is drowning them and everything else out–the gunman, his militia pals, the taxi driver I came here with, and the bystanders waiting just behind the gunman. They have gathered in the rubble and dirt and sunlight to witness the next episode in the endless, bloody, brutal war. I’m the next show. Time to watch an American die.

I am waiting. I say nothing. No begging. No shaking. I prefer this sedate segue, into what, I do not know. The light is brighter than ever. The more I concentrate on it, the more I feel myself drawing inward, away from the soldier and the spectators. I expect the bullets will hit my chest, probably high up near the shirt pocket. He is only a few feet away.

Out of nowhere, I hear my cab driver, who had been sitting in the front seat of the car when the gunman yanked me out. He is yelling something in Arabic.

“Don’t say anything,” he hollers to me in English.

I hear them talking in Arabic. I have no idea what they are saying. My minimal Arabic is no help, and I can’t really see them, because I can’t seem to focus my vision. I can’t even tell how long this has been going on. Seconds, minutes, hours. I’ve lost my ability to think squarely.

I have slipped into a new time zone: suspended time, dying time, captive time, goodbye time.

Several hundred yards away is the museum crossing, the no-man’s zone where I had been headed. This was the plan: From here, where the taxi would drop me off, I was going to run as fast as I could through the thick, loose sand, hoping the snipers on both sides were too busy trying to kill each other to kill me. Then I would enter Christian East Beirut, where I would go through another string of militia checkpoints. But these would be manned by various Christian factions that were working with the invading Israeli soldiers–people not interested in killing me. After invading in June 1982, the Israelis, along with their Lebanese Christian allies, had surrounded the Palestinians in West Beirut, intent on driving the Palestine Liberation Organization from Lebanon.

Driving across West Beirut to the checkpoint had been risky. To keep the Israelis from entering Muslim West Beirut, the Palestinians have filled the streets with mines, though my driver says he knows where they are. What worries him, he tells me as we start out, is an air attack by the Israelis. It happens almost every afternoon and can drag on for hours. And driving on one of the empty streets during a bombing in West Beirut is suicidal. That is why, he says, he wants $100 for a ride of just a few minutes. No problem, I say. This is a lot of money to me but I have no choice. I had approached him by chance amid a long line of taxi drivers several hours ago, asking for a ride to the crossing. He is a tall, thin, balding man in a loose-fitting white shirt and baggy black pants.

“I would like to take you,” he said. “But my vehicle is broken. I need a part for my car. And now with the Israelis around the city I cannot fix it. You cannot find anything here. If you wait for me, maybe four, five hours, I will have the part.”

I reply without thinking. “I will come back,” I say. I tell him this is my first time in war and that I can take this time to think. That starts a conversation.

He thanks me and tells me he needs the money. “I am Christian, you know, and these are not bad people, these Muslim people,” he says. “I live well with them. My wife, she is in a hospital in East Beirut and I cannot go to her. She was hurt in the fighting.”

I tell him I will visit her in the hospital for him. “I will do that for you when I go there,” I say. He smiles and looks away. I don’t think he expects me back.

It was a warm, pretty day: powder blue skies over the rotten smell of garbage and spent ammunition. I was hungry. I felt vaporized. I had barely any money to spare and was living like a scavenger, eating scraps of bread and water and juice mostly. Food in besieged Beirut is too expensive for my budget. My newspaper, the Detroit Free Press, gave me only so much. They told me to come home when it ran out. I don’t want to leave. So I stay on, living in a cheap hotel room.

When I return to the driver several hours later, he is surprised and happy to see me. I tell him I try to keep my word. I don’t ask his name. Too much in my head. I think I will do that later.

In my shirt pocket, as we approach the last checkpoint in West Beirut, is my US passport. We pass every militia checkpoint except the last one, and the passport is what gets me stopped here, on the edge of hell, at the post held by one of the most hardline of the fighters. It is controlled by the Mourabitoun, a group of Lebanese Sunni Muslim militants, mostly leftists inspired by Egypt’s Gamel Nasser. Their name translates as the “marauders,” and they take their inspiration from the fierce defenders at the time of early Islam.

As soon as the cab pulls up to the checkpoint, the militiaman gets up from his chair–a thin, metal beach chair–then saunters over to us, leans into the back window, and asks for my passport.

“A-meri-can,” he howls when he sees the cover.

“You give bomb to Israelis. Israelis kill brother. They use A-meri-can bomb. I kill you.”

I think he said, “yesterday,” that his brother was killed yesterday. I’m suddenly having a hard time thinking.

Then he jerks me out of the car and points up a hill a little way and tells me to stand there and wait to die. Up the small slope towards the wall I march, and here is where I wait, ready. I haven’t said a word. I am wearing a white, short-sleeve shirt–the only clean shirt I have left. I somehow kept it clean. Suzanne would appreciate this, considering my messy ways. I guess I will feel the bullets and then stumble a little and then look down at the rapidly spreading red blotch on my shirt and then, and then … I can see the shirt and all. What a mess. I hate it also that I have thin arms that stick out of the short sleeves.

Just as I am crawling deeper into my whitewashed swoon, my well-lit out-of-body flight, the gunman yells up to me. I have to focus, to listen, to see clearly. Then he tells me to come down towards him.

What?

Moving feet. I stumble forward, unsure what this means. This cannot be good. I don’t know what is happening. My feet are shuffling forward slowly but not the rest of me. I am surprised by this. I hope I don’t shake. I’m not going to cry or beg. I’m not going to wet myself either.

Maybe it is better this way, closer. Faster. Less pain. Bam. Gone. This way you won’t miss, you dumb bastard. Idiot. Asshole.

But he points to the cab driver standing beside him.

“He say, ‘You good man.’ I not kill you. I help you. It is bad.”

Bad? Huh? Oh, my head isn’t working. No. This is wrong. What could get worse?

He points to a place around the bend, through the checkpoint on the way to where the Christian militia is waiting. It is the no-man’s zone in between the Christians and the Israelis on the outside and the Palestinians and their allies inside West Beirut. It is a target range for bored snipers on slow-going sunny afternoons, like this one. Both sides practice their shooting.

“I give you fighter.”

What? This is crazy. You do what?

Then the taxi driver cradles me and shoves me and my bag into the back seat of his small, black sedan. One of the gunman’s colleagues, a young, thin man wearing the same kind of greenish camouflage jacket and carrying a hefty rifle, loops his arm through the window of the car near me. His foot is perched on the outside, and he hangs on. In the other hand he is holding his rifle. This is crazy.

Off we go on a trip lasting seconds. We arrive on the edge of the no-man’s zone. I quickly embrace the driver. I give him the $100. He tells me to hurry and to be careful. I do not know what to say in response to my savior. I am speechless. I forget to ask his name, his wife’s name, the hospital where she is, or why he saved me. I forget to thank him for giving me back my life. I forget what living is like. I am slowly coming back into real time, and it is not easy.

I turn towards another bend in the road, leaving him behind with only a wave. The dirty yellow sand is thick and, as I run, I stumble and fear I will trip before I reach the Christian militia checkpoint.

From there I travel by cab in a haze, making my way to a hotel in Ashrafieh, East Beirut, and promptly up to a room.

There are no windows. “Why aren’t there any windows,” I complain over a telephone to someone at the reception desk.

“Monsieur, there was big car bomb this morning. Many windows were destroyed.”

Hmm.

I am tired and hungry. I barely talk to anyone. I see them–they are mostly foreign journalists–but I don’t connect with them. I am living in my shadow. I do not seem to connect with anything.

At night, I collapse into a coma-like sleep. But a few hours later I bolt upwards and stare straight ahead, and then towards the warm night air pouring through the glassless window. I am in a chilled sweat. I pull the thin white sheets up. Everything seems out of order. I’m exhausted. Shaking. Something has changed me.

One man was about to take my life just because I am an American, a stick figure in the mighty force that he hates. Another man who didn’t know me stood up for me and worked to protect me. And then the miserable, rotten, bastard who would murder me without thinking agreed to help me live. The driver didn’t have to put his life on the line for me. It was an incredible risk and an act of generosity on behalf of a stranger.

Why?

Sweating, shivering, I feel painfully alone and cold in the sea-like darkness.

It is more than 30 years later now as I sit, staring out at a frigid night in Chicago. Yet I am still swimming in that warm Beirut madness and the light that lifted me up. For a long time, I never talked about it. Once I explained to a Palestinian journalist in Gaza what had happened, and he replied that if he were me, he would have never come back to the Arab world. I smiled and let our conversation drift away. It was too difficult to explain why I did the opposite.

I no longer look like that man on the street in Beirut, a stick whose shadow barely falls on the wall behind him. Rather than turning my back on it, I have returned to the Arab world many times. I have lived and worked as a journalist there and been touched deeply. Counting Beirut, I’ve been in five wars and two long, bloody battles between the Israelis and Palestinians. I have called Cairo and Jerusalem home. My Arabic is pretty good now, the product of years of classes and tutors and working on my own, without translators. I plunged into an Arabic class soon after returning to Detroit from Beirut, back in 1982.

Remembering that day in Beirut, I worked to be invisible in the Arab world, though that’s never been truly possible. Once, however, living in Baghdad as a reporter for the Chicago Tribune during the Second Gulf War, a guard at a government building stopped me as I entered a doorway marked for foreigners.

“Brother,” he said in Arabic, “that is not for you.”

“But I am a foreigner,” I replied. Still, Brother.

I gave up a long newspaper career one day in 2008. I had my Don Quixote moment and needed to do good.

Earlier, on a leave from the Tribune in 2006, I had trained journalists in Egypt on a five-month fellowship for the International Center for Journalists. I had been searching for a way to make a difference, and had stumbled onto bloggers raising dissenting voices against the Mubarak regime. Their keen hunger to learn, and their absolute daring, deeply moved me. I got involved.

I learned from them, as well as from other bloggers around the world, and with the help of an imaginative Egyptian human rights lawyer, we created the first guide for citizen journalists in the Arab world. Good journalism was only a part of it. Staying alive was a key message. On the roadway to the Mubarak regime’s collapse, many of these same bloggers were the ones holding up the signs, pointing out the abuse, frustration, and fury that eventually overflowed in Tahrir Square. They were vulnerable.

And so, after leaving the Tribune, I did what seemed natural. I trained Arab journalists, preaching hope for their future as I taught. Hope turned out not to be a lie, but a dream deferred.

A genie has emerged, composed of the internet, of truth-seeking online outlets, of some truly independent newspapers, and of homemade videos; a genie that allows Arabs to talk to each other about their lives and worries, about politics and religion, about all sorts of issues once considered dangerously taboo. I don’t think Arab leaders will ever be able to fully stuff that genie back into its shattered lantern, though some Arab leaders and groups are trying now in Egypt and other places.

Unlike the first days of the Arab Spring, it is clear by now how many challenges face Arab countries that were kept in the dark for ages, held under the thumb of powerful rulers and military leaders for generations.

Will the kingdoms vanish, the dictatorships collapse? Will religious furies abate? They linger on. Seeds of change have been planted, though, and the results will vary. What will rise up in Tunisia, for example, will probably differ from what will come to fruition in Algeria, say, or Libya, or, one day, in Syria. That’s a result of the histories and legacies of each country. For the first time in decades and maybe centuries, the Arab world is a collection of planets spinning in different cycles, and that creates possibilities.

In all of the wars, big and little, all ugly, that I have witnessed, I didn’t flinch, didn’t run, didn’t think twice when someone with a rifle in his hand said he would kill me, or when a bullet hit the man standing near me in a Palestinian demonstration in the West Bank. If I hadn’t died before, I didn’t think I would a second time. I never explained this to anyone. I just wasn’t afraid. Others saw that, and sometimes they wanted to be with me, because I was so calm. I always promised them I would be there for them and we would get out alive. And we did.

But I just said that without thinking. I was caught in the survivor’s cocoon. Caught feeling as if my life was charmed and protected forever. Caught for years in the delusion that I couldn’t or wouldn’t be frightened again. Time, bloodshed, and witnessing the shattered nerves of colleagues–these things eventually cured me.

Still, there’s that afternoon in Beirut.

And so sometimes when the bright light from Beirut returns, crowding out the darkness and cold beyond my window, I know what I did not and could not realize then: that I had been captured by the light.

Stephen Franklin is a former reporter for the Chicago Tribune, the Detroit Free Press, The Philadelphia Bulletin, the Miami Herald, and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. A Pulitzer Prize finalist, he has trained journalists in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Nepal, and Pakistan. He is currently the ethnic and community media director for the Community Media Workshop in Chicago, a nonprofit organization that helps Chicago’s diverse communities and nonprofit organizations tell their stories. He is working on a book about his longtime bond with the Middle East, Captured by the Light.