As jury selection in the alleged Boston Marathon bomber’s trial entered its final stages last week, defense attorneys filed a third motion to move the proceedings to a new location. Lawyers for Dzhokhar Tsarnaev argued that various factors, including “unrelenting” media coverage, had helped create bias among potential jurors in Boston.

The defense’s argument echoes one it made in August, though Judge George O’Toole Jr. wrote responded following month that the team “failed to show that [media coverage] has so inflamed and pervasively prejudiced the pool that a fair and impartial jury cannot be empaneled in this District.” Last week, however, Tsarnaev’s attorneys renewed the claim, citing a questionnaire of 1,373 potential jurors that found 94 percent had been exposed to “moderate” or “a lot” of media coverage.

“[N]ear-daily pretrial publicity in this case — including hundreds of articles in The Boston Globe and Boston Herald that have already been submitted, as well as a tidal wave of online and other media — has cemented a narrative of guilt in the public consciousness that cannot help but be reflected in any pool of prospective jurors in this district,” the defense wrote in a memo supporting its motion. Indeed, 68 percent of potential jurors already believe Tsarnaev is guilty.

A torrent of pretrial publicity helped secure a rare change of venue for the likes of Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh. But shifts in the media environment over the past 20 years have raised questions over whether excessive coverage is now the rule, rather than the exception. Some legal scholars argue that changing locations to limit any effects of press reports has been rendered useless by non-stop cable news and omnipresent digital media. If coverage of the alleged Boston bomber is any indication, the practice by judges — and more often the argument by defense attorneys — is archaic in high-profile cases.

“Change of venue, in response to prejudicial coverage in a particular area, may no longer be effective in the age of the Internet, when newspapers keep archives of back issues obtainable online,” British law professor Gavin Phillipson wrote in a paper presented at Duke Law School in 2007. “Nor will it assist when the prejudicial publicity was carried by national newspapers or television stations.” Or digital media outlets with audiences spread nationwide, for that matter.

The marathon bombings and ensuing manhunt consumed national media starting April 15, 2013. CNN’s viewership almost doubled that week, averaging nearly 1 million viewers throughout the day. Fox, meanwhile, led all primetime programming — not just news — by averaging 2.87 million viewers. When the pursuit of Tsarnaev reached its dramatic conclusion on April 19, special coverage on NBC, ABC, and CBS combined for 25 million viewers. It was the most-tweeted sports-related event of 2013, according to Twitter.

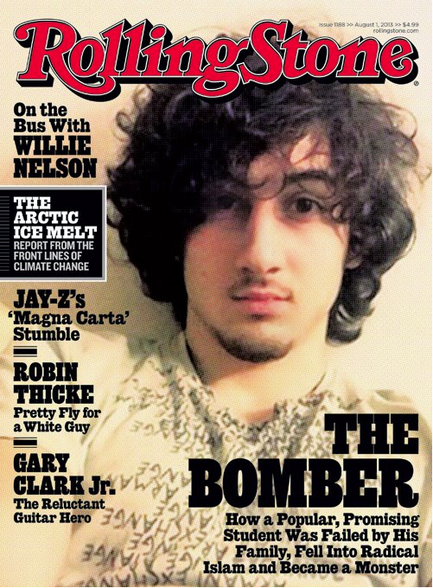

The atrocity and its aftermath made the covers of The New Yorker, Sports Illustrated, and Time. A Pew Research Center poll taken the following week found that 63 percent of Americans had followed the news “very closely,” a rate equal to that of the Iraq War and greater than that of the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections. After Rolling Stone plastered Tsarnaev’s face on its cover that July, the magazine’s newsstand sales doubled.

The atrocity and its aftermath made the covers of The New Yorker, Sports Illustrated, and Time. A Pew Research Center poll taken the following week found that 63 percent of Americans had followed the news “very closely,” a rate equal to that of the Iraq War and greater than that of the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections. After Rolling Stone plastered Tsarnaev’s face on its cover that July, the magazine’s newsstand sales doubled.

“You can take for granted that coverage is going to be hostile to any defendant in the first place,” said William Loges, an associate professor of new media communications at Oregon State University. “But when you combine all the available remedies in a normal trial, let alone a change of venue, chances are the effects of media coverage can be minimized.”

Those tools include the voir dire process of questioning potential jurors and judges’ instructions once they’re picked, among others. Loges added that a combination of jurors’ proximity to a crime and their personal stake in its fallout comprise a much stronger case for a change in venue. Tsarnaev’s lawyers argued both in their memo last week, noting that 69 percent of potential jurors have some sort of personal connection to the crime and its aftermath. The defense team included the media angle to emphasize its point.

Legal scholars for years have analyzed how a changing media landscape may affect defendants’ right to an impartial jury, which is guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment of the Constitution. The “media environment in which Americans now live is profoundly different from the environment that prevailed 200 years ago,” Christina Studebaker and Steven Penrod of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln wrote in 1997. “As media coverage becomes more extensive and accessible, it is likely to become more difficult to find jurors who have not been exposed to relevant pretrial publicity.”

The advent of 24-hour news channels coincided with audiences’ growing appetite for coverage of high-profile legal cases — the O.J. Simpson murder trial, for example — nationalizing such stories of crime and punishment. The trend has only accelerated with the rise of online and social media.

The debate over pretrial publicity reached the Supreme Court in 2010, when former Enron executive Jeffrey Skilling contended his conviction on fraud charges in Houston came in an unfair trial tainted partly by negative media coverage. Then-Solicitor General Elena Kagan argued in a brief that if pretrial publicity precluded selection of an impartial jury, “then no venue will be acceptable, and no trial will be possible, in the most nationally significant cases. That cannot be the law.” The court ruled against Skilling’s media argument, with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg writing in the majority opinion, “Prominence does not necessarily produce prejudice, and juror impartiality, we have reiterated, does not require ignorance” (emphasis hers).

Several trials have attained such media prominence in recent years — those of Scott Peterson, Casey Anthony, and George Zimmerman, to name a few. And moving their locations would have similarly done little to limit any potential effects of media coverage on jurors. In response to this apparent quandary, a number of scholars including Susan Duncan, dean of the University of Louisville’s law school, have called for imposing a British-style model that limits reporting on judicial proceedings.

That would be a seismic philosophical change to the American system, recalibrating the balance between the First and Sixth Amendments. Boges, who also co-authored a book on pretrial publicity, said that the current structure includes more than enough safeguards.

“Even with the expanded nature of media and overall media saturation,” Loges said, “if we don’t believe that a high-profile jury can’t come to a fair verdict in a big city like Denver or Boston, we might as well give up on the jury system.”

David Uberti is a writer in New York. He was previously a media reporter for Gizmodo Media Group and a staff writer for CJR. Follow him on Twitter @DavidUberti.