That local journalism is facing tough times is now an accepted fact. There are plenty of stories of local newspapers closing and journalists losing their jobs. But what’s been lacking in the discussion, beyond the anecdotes, is hard data.

So we at the DeWitt Wallace Center’s News Measures Research Project have been trying to: first, document the extent to which communities have access to robust local journalism; and second, determine whether certain types of communities are more at risk than others. We wanted to do this in a way that didn’t just look at the presence or absence of news outlets in individual communities, but rather examined the quantity and quality of journalism being produced.

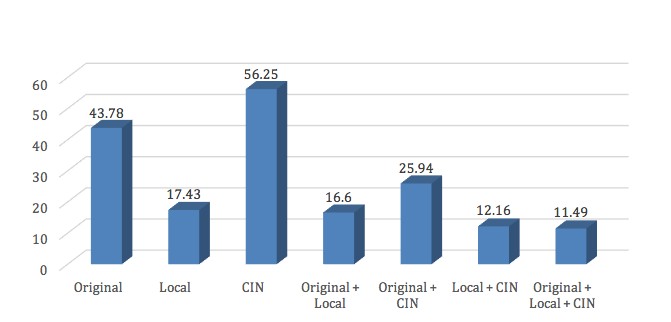

Our findings, we believe, provide a useful snapshot of the state of local journalism today, and how local news outlets are responding to the economic challenges they face. We found, for instance, that of the 100 randomly chosen communities across the US that we analyzed, a full 20 of them received no local news stories in the seven days that we analyzed. Twelve communities received no original stories during this time period; and eight received no stories addressing a critical information need. On average, in terms of the news stories produced for the communities in our sample, 44 percent of the stories were original; only 17 percent were local; and 56 percent addressed what we call a critical information need—they provided hard news or information in the public interest, as opposed to soft news like celebrity gossip. Read the full study here.

While it is difficult to interpret these numbers without having data over a long period of time, it does seem reasonable to say that, at minimum, there is a real shortage of reporting about local communities. It is perhaps also concerning that the majority of reporting that local media outlets provide is not produced by them; and that barely half of their reporting addresses a critical information need. When we apply all three criteria to the stories we gathered, we find that, on average, only about 11 percent of the stories are local, original, and address a critical information need.

RELATED: When local papers close, costs rise for local governments

To do this work, we partnered with the Internet Archive, the organization that digitally archives as much of the web as possible. However, even the Internet Archive can’t store the entire history of the web, and local news sites tend to fall through the cracks. So, the Internet Archive created a custom archive for our project, examining the URLs for every television station, radio station, newspaper, magazine, and online news site from 100 randomly sampled US municipalities. Those home pages were then archived, along with every page linked from those home pages, for seven randomly selected days. This gave us the ability to count and content analyze every news story on those home pages, in order to get a sense of the quantity and quality of the local news being produced in each community.

To keep things simple (since we had about 16,000 stories to analyze), we focused on three characteristics of each news story. The first was whether the story was original. That is, was it produced by the local media outlet, or was it a story produced by another news organization, and just being linked to (or republished) by the local outlet? One of the challenges confronting local news outlets these days involves covering the costs of original reporting, so we thought originality provided a useful indicator of the robustness of local journalism. The second characteristic was whether the story was local. For local news outlets to serve their communities effectively, they need to provide them with news and information about their community; but the reality is stories with a broader focus can often generate larger audiences; so we thought whether a story was local provided another important indicator of the robustness of local journalism. Finally, we looked at whether each story addressed what we call a critical information need. Critical information needs refer to categories of news stories that are important to creating a well-informed citizenry, like education, the economy, and civic/political life. Here, we were attempting to get at the extent to which local news outlets are providing substantive reporting, rather than, say, the latest activities of the Kardashians. In today’s media environment, the economic incentives to focus on less substantive topics can be quite strong.

The mean proportion of total stories by story type (n=100; CIN stands for “critical information need”).

Finally, we looked at whether certain community characteristics might be related to the robustness of local journalism. Controlling for population size, we found that communities that are further from a large media market see more stories overall, and more stories addressing a critical information need. This suggests that, to some extent, large-market journalism can flow into surrounding communities and undermine local journalism. We also found that communities with larger Hispanic/Latino populations receive less original and local journalism. This could be a reflection of the greater interest in international news amongst immigrant communities; but also could suggest that Hispanic/Latino communities are not being as well served by their local news media.

Finally, we found that the number of universities in a community is positively related to the total number of stories, number of original stories, and number of stories addressing a critical information need, largely because of the number of local media outlets that they tend to operate. We hope that all of these findings will be useful to the growing number of organizations and funders dedicated to sustaining and revitalizing local journalism.

This research was supported by the Democracy Fund.

ICYMI: A tale of two companies: NYT profits while Tronc considers sale

Philip M. Napoli Philip M. Napoli is the James R. Shepley Professor of Public Policy at the Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke University. He is the author of Social Media and the Public Interest: Media Regulation in the Disinformation Age.