In today’s New York Times, Binyamin Appelbaum notes what is thus far one of the most salient facts of the 2012 campaign:

WASHINGTON — No American president since Franklin Delano Roosevelt has won a second term in office when the unemployment rate on Election Day topped 7.2 percent.

Seventeen months before the next election, it is increasingly clear that President Obama must defy that trend to keep his job.

Roughly 9 percent of Americans who want to go to work cannot find an employer. Companies are firing fewer people, but hiring remains anemic. And the vast majority of economic forecasters, including the president’s own advisers, predict only modest progress by November 2012.

To nitpick for a moment, the bulk of the research on voting shows that, historically, it is growth in real disposable income, not the unemployment rate, that is a key factor in both presidential (pdf) and midterm elections. But since many of the jobs that are being created, including those that make up the “manufacturing renaissance,” are in the not-so-exciting low-wage sector, that fact may not be much comfort to the current incumbent. And in any case, Applebaum’s emphasis on the economic roots of political outcomes is welcome.

As is his point that in spite of the persistently depressing economic news, nobody in power seems able or willing to actually do anything about it. Appelbaum runs through the much-reported partisan stalemate on Capitol Hill, and the White House’s subsequent abandonment of another big “stimulus” effort, before shifting his attention:

The Federal Reserve, the nation’s central bank, has the means and the mandate to reduce unemployment by pumping money into the economy…

Now, however, the leaders of the central bank say they are reluctant to do more. The Fed’s chairman, Ben S. Bernanke, said in April that more money might not increase growth, but there was a growing risk that it would accelerate inflation.

Congress charged the Fed in 1978 with minimizing unemployment and inflation. Those goals, however, are often in conflict, and the Fed has made clear that inflation is its priority. Fed officials argue in part that maintaining slow, steady inflation forms a basis for enduring economic expansion.

Eric S. Rosengren, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, said in a recent interview that the Fed had reached the limits of responsible policy.

This is important, and under-discussed, stuff. While the Fed’s actions to support the big banks at the height of the financial crisis have come in for (deserved) scrutiny, its responsibility for restoring the economy to health has been relatively undercovered. It’s good to see a story noting that monetary policy is a big deal–and that the Fed’s decision not to do more reflects a conscious choice, rather than a fact of nature–make it onto the front page.

Meanwhile, in The Wall Street Journal, Jon Hilsenrath offers more details about the Fed’s thinking:

Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke signaled in April that the hurdle to more “quantitative easing,” as it is known, is very high and Fed officials have done nothing to indicate that Mr. Bernanke’s guidance has changed as economic data has worsened in recent weeks….

In comments last week, St. Louis Fed president James Bullard said the Fed was entering a period in which Fed policy will be on pause—meaning it won’t be trying to push interest rates either higher or lower. Charles Evans, president of the Chicago Fed and a strong advocate of past programs, said earlier last month that what the Fed had done already was “sufficient.”

In comments Wednesday, Cleveland Fed president Sandra Pianalto said the Fed’s current stance was appropriate and added the recovery was likely to continue, even though growth “may be frustratingly slow at times.”

Again, this is important stuff. And since Bullard, Evans, and Pianalto-—like Rosengren–are generally part of the dovish contingent at the Fed, these remarks strongly suggest the central bank won’t be trying to boost the economy again anytime soon.

One point that doesn’t quite come through in either of the stories is just how focused on low inflation the Fed has become. Hilsenrath notes that the prices of so-called TIPS bonds indicate investors expect inflation of 2.8 percent in five years, and in April consumer prices were up 3.1 percent from a year earlier. Both are above the Fed’s unofficial but widely acknowledged goal of 2 percent inflation.

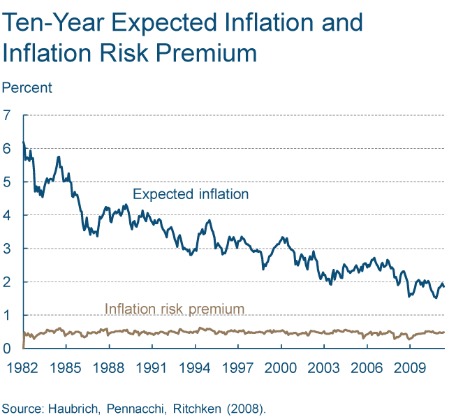

But according to another measure of inflation expectations, produced by the Cleveland branch of the Fed itself, the “latest estimate of 10-year expected inflation is 1.86 percent”–that is, below the goal.

And from the same source, here is a graph showing ten-year inflation expectations (the blue line) going back to 1982. There’s a long-run trend, and it’s not upward:

There are good questions, which Fed officials have noted, about how effective further easing would be. At the same time, there are good questions about why, with a pressing jobs crisis and signs of problematic inflation scarce at best, the central bank isn’t trying everything it can to boost the economy. As the political press devotes more and more of its time to the budget battles on the Hill and the campaign to come, we need some reporters who will ask them.

Greg Marx is an associate editor at CJR. Follow him on Twitter @gregamarx.