It was one of the weirdest weeks Albany has ever experienced—and for New York’s scandal ridden, incestuous capital, that’s saying something. It was early February 2010, and a New York Times investigative team was focusing on Governor David Paterson—just what the resulting story would say no one knew, not even the reporters at work on it.

But in a city where gossip and rumors swirl, the governor’s press staffers soon found themselves denying lurid stories about the governor’s sex life, often to reporters who had no reporting substantiating the tales.

One of those reporters was Michael Gormley, the Associated Press’s capitol editor. Elements of his work are recorded in e-mails the state released in response to a Freedom of Information Law request made by CJR. According to one accounting in the release by Gormley—crafted, he wrote, to “win back” the trust of the governor’s communications director—the AP’s pitched debates over how to fairly cover the maelstrom set off internal “panic” and put Gormley’s job on the line.

The Associated Press’s wire has unrivaled reach, and a sterling reputation for ethics. If the wire wrote up the rumors permeating Albany, even in a denuded form, their jump to the media’s mainstream would be complete, available for publication around the world, and sure to be followed on by every news outlet in the state—and many across the country.

While the governor’s press secretaries rotely batted away inquiries with variations on “all rumors are false,” rumors of an impending, incredibly damaging, New York Times piece quickened into written words on Friday, February 5, with blog posts and a tweet.

While the state’s newspapers stayed quiet on the mess through the weekend, on Super Bowl Sunday, the Associated Press broke its silence.

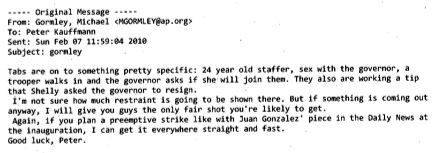

Just before noon that day, Gormley wrote to Peter Kauffmann, the governor’s communications director, seeking to turn the very things the governor’s press staff had to fear about the AP into an asset, and relating two rumors (one rather lurid) that he’d heard:

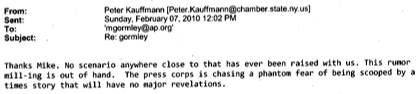

Kauffmann wrote back denying that they’d been asked about anything like that:

That evening at 7:17, less than an hour after the game’s kick off, Gormley emailed Peter Kauffmann to tell them that he expected the AP would run a story that night saying that he had learned the governor had been discussing his “future in the job” with legislators. The e-mail mentioned “unspecified personal issues” that the New York City tabloids might write on.

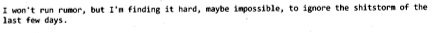

Gormley wrapped up his e-mail with a line suggesting the AP felt it had no option:

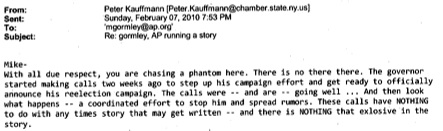

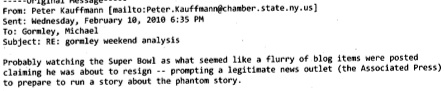

Kauffmann fired back, trying to persuade Gormley that he was “chasing a phantom”:

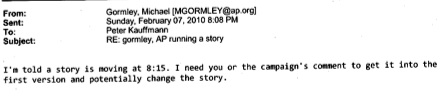

But the AP would not be deterred from getting something out. Gormley emailed Kauffmann to let him know that his opportunity to comment for the AP’s story was rapidly closing.

The wire ran a thirteen-paragraph story, with an opening sentence stating that “questions swirl around the state capitol about unproven accusations involving … personal conduct.” Kauffmann’s pushback from the 7:53pm email made it into the story verbatim, except that it was attributed to Richie Fife, then Paterson’s 2010 campaign manager. (Fife, beyond offering that it was a “brilliant quote,” declined to comment on how Kauffmann’s words came to be attributed to him.)

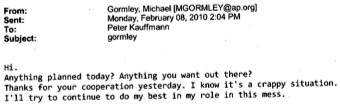

Gormley had told Kauffmann that he was scheduled to fly to Washington on Sunday or Monday to attend a conference, but in the midst of the weekend’s chaos he scuttled the trip. He e-mailed Kauffmann at 2pm:

An hour later, Kauffmann emailed Gormley to ask if he was in Albany and could come and conduct a face-to-face interview with the governor in about a half hour. Kauffmann promised his staff would find a “discrete way” for the meeting to take place.

Gormley wrote up the interview, where the governor denounced a New York Post Page Six item from January 30, claiming state troopers had caught him “snuggling” a woman who was not his wife as a fabrication, and complained that the unpublished Times story had “spawned a bunch of speculations that are so way out that it’s shocking.”

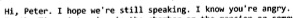

Kauffmann’s reaction to Gormley’s work over this two day period isn’t recorded in detail by the emails, and he declined a request to comment. But the morning of Tuesday, February 9, the day after Gormley’s sit down with the governor, the reporter emailed Kauffmann to ask for some information about the interview the New York Times had scheduled with governor that day. The e-mail opened with a line that suggested Kauffmann was not too happy:

The state’s e-mail release records no response to Gormley’s entreaty.

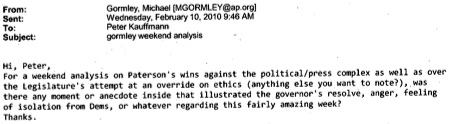

He e-mailed Kauffmann again on Wednesday, seeking a bit of color or anecdote for a piece he had in the works:

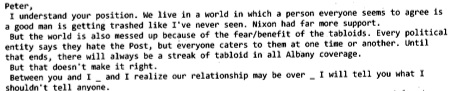

Kauffmann’s response, which in contrast to most of Gormley’s promptly returned e-mails, came after an eight hour delay, probably wasn’t what Gormley had been hoping for.

Gormley then wrote and sent an e-mail to Kauffmann that not only did he later claim he never meant to send, but one that he would eventually write “took far more poetic license than was reality in describing the internal discussions.”

But just which portions were “poetic license” is unclear. It is unlikely that every point in Gormley’s original e-mail is fiction. Sent on Thursday, February 11, it provides a timeline and other details that match up with Gormley and Kauffmann’s e-mail traffic from Super Bowl Sunday. It is an emotional telling of struggles with editors over how to appropriately cover the story, where Gormley portrays himself as pushing back against editors who wanted more a more salacious dispatch than he felt the situation and reportable facts merited, and who wanted to run a story without what Gormley considered adequate comment from the governor’s camp.

Michael Gormley did not respond to requests for comment on the e-mails, and Paul Colford, an AP spokesperson, declined to make Gormley or the relevant editors available to discuss the matter. Instead he e-mailed a brief statement describing Gormley as “hard-nosed reporter who was trying to be fair and accurate in his coverage of the governor” and declining to “discuss the internal give and take among staffers in pursuing stories.”

The original Gormley e-mail opened with some unloading on the state of affairs in Albany, and then moved to a promise to dish him some dirt about what happened at the AP on Super Bowl Sunday:

Gormley then claimed that on Super Bowl Sunday he was facing heavy pressure from “a top editor” to run a story “that simply said, based on a rumor from a reporter who heard it from a tabloid reporter, that the governor was going to resign” and that the “same sourcing told” the editor that State Assembly Speaker Shelley Silver had asked Paterson to step down. The Silver rumor, and the assertion that the “tabs” are on it, is cited in Gormley e-mail’s around noon to Kauffmann.

Gormley wrote that the was able to share reporting with this editor that showed the Silver and resignation rumors weren’t true, but that that only had “slowed his assumption down.”

In Gormley’s original e-mail, he also wrote that things came to a head when editors pressured him to move a story at 8:15 that night that did not contain what he judged to be adequate comment from the governor’s camp. Gormley wrote that only two minutes before the article was set to run he told the editors that without Kauffmann’s comment on the record he was withdrawing his byline, effectively killing the piece. This 8:15 deadline, and a desperate attempt to get comment by it, is also reflected in the released Super Bowl Sunday e-mail traffic.

Gormley claimed that his efforts that night “blocked” a story that “everyone was ready to do,” and even quoted the slug for this claimed spiked story: “ALBANY _ Gov. David Paterson is considering resigning amid persistent rumors about his personal behavior.”

The e-mail closed with a paragraph-by-paragraph defense of the fairness to the governor of the story the wire ultimately ran.

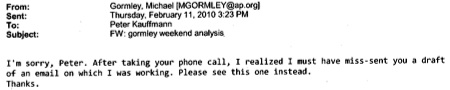

About three hours after he sent the original e-mail giving a detailed accounting of the AP’s inner struggles on Super Bowl night, Gormley e-mailed Kauffman, saying that the original e-mail had been a draft he never meant to send.

The version he asked Kauffmann to consider in its stead omitted all details of internal deliberations, briskly moving on to the Gormley’s defense of the story the AP ran.

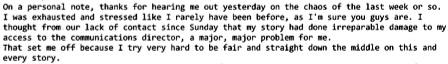

On Friday, in the message where he further distanced himself from the detailed narrative presented in Thursday’s original e-mail by claiming he’d used “poetic license,” Gormley wrote Kauffmann that the original e-mail was written “to make the case for my efforts…and win back your trust,” contradicting a claim in the original e-mail where he claimed he wasn’t spilling the details for “credit.”

In the previous weeks, Gormley and Kauffmann were exchanging beer league softball stories over e-mail, and joking about the agony of having to sit though thirty-some minutes of ABC’s The View before the Governor took to the couch for a January appearance. In the Friday e-mail where Gormley claimed that he’d taken unjustifiable poetic license, he described what prompted him to write the draft.

Gormley closed by saying that “despite what I like to say about the accuracy of what I print, my email account was just wrong in tone and content,” apologized again, and then asked Kauffmann out for beers.

The e-mails do not reflect if they ever met to drink any.

(A selection of Gormley’s emails to Kauffmann can be downloaded as a .pdf here.)

Clint Hendler is the managing editor of Mother Jones, and a former deputy editor of CJR.