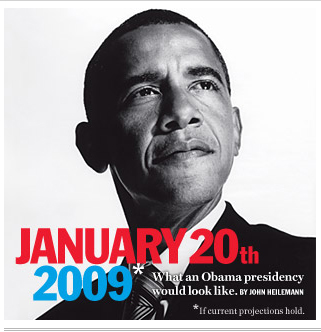

The cover of this week’s New York magazine features a black and white photo of Barack Obama Looking Presidential, slugged “January 20th 2009” in red and blue and subheaded, in white, “What an Obama Presidency Would Look Like.” Next to the bright-blue “2009” is a small, white asterisk.

Its footnote? “If current projections hold.”

In other words: Conjecture! Conditionals! Would! If!

Which, you know: Cheeky, sure. Ironic, definitely. Combine those, and you could even call the thing Witty. (Most asterisks, when inserted into in prose both journalistic—MoDo!—and literary—Vonnegut! Foster Wallace! Eggers!—are.) But the asterisk here, and the fine-printed caveat it indicates, also amount to a tacit—and smug—admission that, in projecting an Obama presidency before such a thing has transitioned from fiction to non-, New York is breaking the rules of journalism. We know we’re not really supposed to report on stuff until it’s actually happened, the headline declares, but we’re going to do it anyway. The asterisk is a rhetorical wink: to readers who are ready for the campaign to be over with, already, and to journalists who understand the rules as much as they’re inclined to break them. In this, New York‘s cover is suggestive of its (in)famous New Yorker counterpart: It’s about narrative as much as it is about image—or, rather, it’s poking fun at narratives through image, juxtaposing what journalists want to be talking about versus what they should be talking about. It’s reportorial Id and Superego rolled into one.

And what brings the two together, in this case, is numbers. Polling numbers, specifically. Here’s New York‘s rationale for its own Obama Presidency Projection story, rendered fantastic only by virtue of its being authored by John Heilemann:

From the moment it became clear last spring that Obama would be the party’s standard-bearer, the excitement over what he represented has been twinned with a gnawing dread that his astonishing ride would somehow come to a crashing end a few yards short of the White House. That America would prove unready to elect a black president. That the Republicans would once again work their voodoo on the electorate. Or that Obama would choke in the clutch—that, far from being the next FDR or JFK, he would turn out to be the reincarnation of George McGovern or Mike Dukakis or John Kerry.

But as the outcome of the race has begun to seem more certain with each passing day—with Obama’s lead in the polls healthy and showing few signs of diminishing, with John McCain’s campaign listing aimlessly and lapsing into rank self-parody, with Sarah Palin devolving into a human punch line—Democrats are slowly, haltingly allowing themselves to believe that victory is truly within their grasp, and hence to contemplate what comes next. Transition. Inauguration. Those first hundred days. Maybe even, perchance, with augmented majorities for the party in both the House and Senate all but in the bag, the dawning of a spanking-new era of Democratic dominion.

In other words, per New York: A long cover story about an as-yet-fictional Obama presidency is justified because the polls are currently in Obama’s favor.

First of all, Democrats, progressives, liberals, socialists, union members, young people, independents in want of a change, Obamacans, and anyone else who currently wants Obama to win the election should probably go find the nearest table, chair, or other chunk of wood and knock on it.

Second of all, it should go without saying that New York and all the other news outlets that are doing similar bits of forward-looking speculation right now—from The New York Times to The Atlantic to the Boston Globe to the New York Post to the Huffington Post—are venturing into dangerous territory with their “what an Obama presidency would look like” stories. Articles written in the conditional tense always occupy a rather precarious section of the journalistic landscape. And particularly so when the conditions in question are determined by polling numbers, whose reliability is itself precarious (hence the ominous “Remember New Hampshire” we hear voiced among pundits every now and then). And even more particularly so during the closing days of a campaign—early voting has already begun in many states—and therefore during that strange window of time in which speculation moves from being merely “theoretical” and “idea-driven” and toward being, simply, audacious.

For journalists, there’s a rule of inverse proportionality to be followed, it would seem, when engaging in political speculation: The more likely a candidate is to win the presidency, the more restraint journalists need to demonstrate when discussing that victory. Journalists are at their leisure to speculate all they want, for example, about What a Ron Paul Presidency Would Look Like, or an Al Gore presidency, or a Condi Rice presidency—because, currently, such administrations are highly unlikely. The discussions would be based on theories and ideas, rather than on concrete possibilities. They couldn’t be deemed “influential,” in the most literal sense of the term, because there’s nothing at stake to, you know, influence. An Obama presidency, on the other hand, is likely; as such, journalists need to be particularly careful when they talk and write about it. There’s a fine line, after all, between being on the right side of history and affecting which side history lands on.

Heilemann, guesting on yesterday’s Reliable Sources, justified his forward-looking approach to Howard Kurtz like so: “Well, you know, one wants to try to be ahead of the curve, I guess, Howie.” And fair enough. Except that, as we’ve said before, the American electorate generally doesn’t appreciate being treated as a foregone conclusion. The curve Heilemann referred to is paradoxical: For journalists, being ahead of that curve often means stepping back and allowing the curve to take shape in the first place. Just as being on the right side of history often means stepping back and allowing history to be made.

Megan Garber is an assistant editor at the Nieman Journalism Lab at Harvard University. She was formerly a CJR staff writer.