This is the sixth in a series of posts that discuss how possible changes in Social Security will affect the residents of Champaign-Urbana, Illinois. The entire series is archived here.

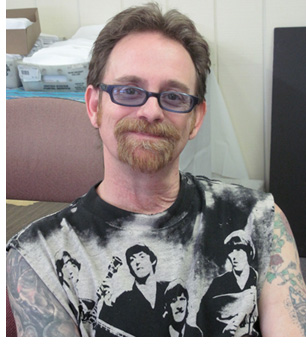

Jim Bean is just the sort of person Social Security is intended to help. He is also the sort of person at whom the controversial recommendations from the co-chairs of the president’s deficit commission take direct aim. For Bean, now age fifty, waiting until sixty-seven to retire will be a stretch—let alone sixty-eight or sixty-nine, which might become the new retirement ages if deficit commission co-chairs Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles have their way. Bean is a rigger—the person who climbs up to the ceiling in theaters and entertainment centers to hang the lights and the sound equipment, and do whatever else is needed to make a production work. He currently operates the spotlights.

“It’s an inherently dangerous thing to work 100 feet in the air,” he says. “Eventually I’m not going to be doing rigging. There will be a time by the time I am sixty that I won’t want to do it.” Or, if something goes wrong, he may not be able to do it. Given his work history, an early benefit from Social Security when he is sixty-two will be low, although he didn’t know how much it would be. If the retirement age is raised and the early retirement age does not go up as well, his early retirement benefit could be very low, a point that has not been discussed up to now. The Simpson-Bowles proposal suggests a hardship exemption for people who must take their benefits at age sixty-two. Who knows whether Bean would fall into that category?

“It’s an inherently dangerous thing to work 100 feet in the air,” he says. “Eventually I’m not going to be doing rigging. There will be a time by the time I am sixty that I won’t want to do it.” Or, if something goes wrong, he may not be able to do it. Given his work history, an early benefit from Social Security when he is sixty-two will be low, although he didn’t know how much it would be. If the retirement age is raised and the early retirement age does not go up as well, his early retirement benefit could be very low, a point that has not been discussed up to now. The Simpson-Bowles proposal suggests a hardship exemption for people who must take their benefits at age sixty-two. Who knows whether Bean would fall into that category?

Bean, a wiry man with lots of tattoos, says he likes his job, but it’s not full-time employment. When classes are in session at the University of Illinois, he works at the Krannert Center for the Performing Arts. He is busy when there are performances. But in his business there are dry spells, although when he works the hourly pay is good. Sometimes he can make $28.50 an hour, or as much as $32 if he gets jobs in places like St. Louis. “I don’t see my income rising above $20,000,” Bean told me. “I’m not in the local (union) and do miss out on some jobs.”

We talked about Social Security disability benefits, which he had heard of but didn’t understand. “Riggers don’t carry insurance,” he said. “In our job people don’t get hurt, they die. You know that when you go up.” Between jobs as a rigger, he works as a musician. He’s a lead singer in one band and plays guitar in another. He says he lives very frugally in a tiny apartment in Champaign and helps his daughters, ages twenty-two and twenty, when he has extra money. “My oldest daughter got straight As in junior college and is now attending the University of Illinois with financial aid,” he said. “That girl has done a lot and has as much support as I can give. She has done real well.”

Our conversation got around to health insurance and health care. It turned out that Bean had had lots of interaction with the health care system. His predicament was featured in The Wall Street Journal seven years ago, as part of a piece about the aggressive collection tactics of Champaign’s Carle Foundation Hospital. Bean was uninsured, as he is now, and attempted suicide. He said he blew a hole in his shoulder that required three surgeries at Carle Hospital in 1991, when he was despondent over the break-up of his marriage. Bills piled up, and the hospital sued him. He missed some court dates and hospital lawyers got a warrant for his arrest—a body attachment, the Journal called it. He briefly landed in jail until his brother bailed him out. When the story was published, Bean was making payments to the hospital, which had agreed to drop the interest charges on the bill. His current health plan, he says, is not to get sick.

Bean knew about proposals to raise the Social Security retirement age. “When I read it, I thought it was great news that we’re living longer, but it’s not great news financially,” he told me. “It’s not great news that they’re forcing people to work more years.” Then he talked about his father. “If they had made my father work another five years, it would have killed him.” He worked as an electrician who helped build nuclear power facilities. “He’s seventy-two now and retired seven years ago. To force someone like that to work five more years seems like a crime.”

Yet Bean said he could see both sides of the issue. But he did worry about fairness and changing the rules of the game: “To tell people at the end, we’ve changed the rules, that’s not fair at all.”

For more from Trudy Lieberman on Social Security and entitlement reform, click here.

Trudy Lieberman is a longtime contributing editor to the Columbia Journalism Review. She is the lead writer for CJR's Covering the Health Care Fight. She also blogs for Health News Review and the Center for Health Journalism. Follow her on Twitter @Trudy_Lieberman.