With a debt ceiling agreement apparently at hand, Matthew Yglesias makes an important point that I haven’t seen in the write-ups from major outlets: even if you accept the very debatable proposition that the deficit should be Item 1 on the agenda in D.C. right now, the deal doesn’t really grapple with the overriding source of long-term deficit projections, which is the skyrocketing cost of medical care.

Health care costs aren’t primarily responsible for the debt the U.S. has accumulated to date, or even what will pile up in the next few years—as a famous-among-wonks chart from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities shows, the Bush tax cuts, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the Great Recession are largely to blame for that.

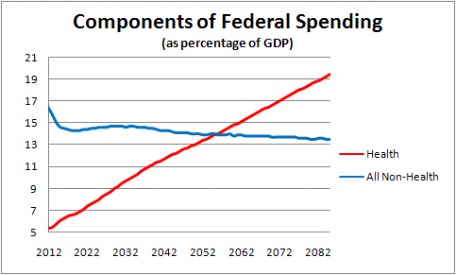

But health care is at the core of the long-run budget challenge. Via an earlier Yglesias post, here’s a chart compiled by National Review’s Yuval Levin based on spending projections from the Congressional Budget Office (for purposes of comparison, total federal spending has tended to hover around 20 percent of GDP for the last several decades):

Obviously, there’s a lot of uncertainty about estimates of spending seven decades out, but the direction of the two lines is striking. And it’s hard to imagine, within the boundary lines of American politics, any solution—whether higher taxes, cuts in other areas, or some combination—that would accommodate all of the cost growth represented by that red line. So the long-term budget fight will be partly about what taxes and cuts to accept, but mostly about what represents an acceptable, effective way to change the slope of that line. Levin glosses it this way: “Simply put, [the] debate is all about health-care entitlements. And I mean all.”

But the tortured debt ceiling debate in Washington, and much of the coverage surrounding it, rarely reflected that insight. A variety of Medicare reforms, along with revenue increases that would help cover rising costs, were reportedly discussed as part of the “grand bargain” sought by President Obama. But the deal we’ve apparently ended up with—or the parts of it we know about now, anyway—targets its cuts on the parts of the budget represented by the blue line above, and does comparatively little (though not nothing) about the scary-looking red one.

It may be possible to overstate this line of criticism. I spoke this morning with David Leonhardt, the new Washington bureau chief for The New York Times, for a Q&A that will appear soon on the site. Leonhardt has written about the centrality of health care costs to the long-run budget challenge, but he also said it would be a mistake to dismiss out of hand the search for deficit reduction in other areas. “Anything that doesn’t deal with health care almost certainly doesn’t come close to solving our deficit problem,” he said, “but it could still be meaningful.”

It’s a fair point. And to add another, it’s no journalistic felony that we’re not seeing lots of stories today that emphasize the disconnect between the agreed-upon spending cuts and the long-run budget challenge. Today’s news is the fact of a deal and what is in it, after all. And the natural life cycle of these things is that today’s smart blog post becomes tomorrow’s (or the next day’s) newspaper article.

Still, with budget fights likely to be at the center of politics for the foreseeable future, it’s vital that reporters understand, and explain to readers—over and over again—the primary source of our long-run fiscal challenge. Bringing the growth of health care costs under control will be extraordinarily difficult to begin with, because of real policy hurdles, entrenched interests, and fundamental disagreements about what represents a desirable solution. It will be even harder if the press fails to explain the nature of the problem.

Greg Marx is an associate editor at CJR. Follow him on Twitter @gregamarx.