When most Americans met Jeremiah Wright, he was a caricature, rendered in the blurry lines and crackling tones of buffered video bites: a seething figure in vaguely African garb, preaching fire and fury, waving his hands, glaring at no one in particular, and questioning the goodness of America. He yelled. He pounded his fist. He indulged in his anger. And in the news, his story played out as one of his sermons: in climbs and drops and loops and twists, a roller coaster of rhetoric so fast and furious and jarring and breathtaking that the only possible reaction to it all was to go, unthinkingly, along for the ride.

Only when the story was ending—when it was too late to be rectified, which is generally the time we in the media choose to recognize our mistakes—did we begin to feel the whiplash. We had, in attempting to encapsulate both a man and a religious tradition in a series of seconds-long video clips, shortchanged our audiences even as we tried to enlighten them.

Then Barack Obama delivered his speech on race in Philadelphia, giving context to Wright’s anger and calling, on a national scale, for empathy, reconciliation, conversation. “It was like ripping the Band-Aid off,” Chris Matthews put it. It was “game-changing.” It was “transformational.” The Great Conversation about Race in America—the one older than the country itself, the one that has been waged in fits and starts for nearly four hundred years—was again upon us, this time with new voices and renewed urgency. This was our moment. From now on, things were going to be different. We, the people—guided by a press ennobled and invigorated by the opportunity—were embracing our pivotal historical moment to transcend history itself, to confront and, perhaps, finally exorcise our demons by engaging in that most fundamental of American pastimes: an open-minded and frank conversation.

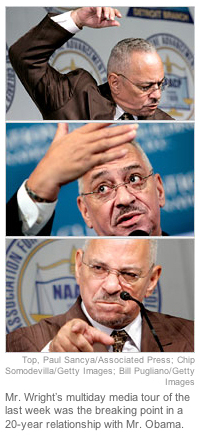

Except, of course, we weren’t. They didn’t. It couldn’t. All our lofty talk of Reconciliation was interrupted—and quickly revealed as hopelessly ironic—when Jeremiah Wright reemerged on the scene last week. You know the story. The interview with PBS’s Bill Moyers, in which the pastor claimed the incendiary video clips that had defined his media portrayal were taken—as they generally tend to be when a portrayal is negative—out of context. The “fiery” speech to the Detroit NAACP. The “inflammatory” appearance at the National Press Club. Of course the Conciliatory Conversation fizzled in our faces. How could we focus on all we have in common when Reverend Wright himself seemed so focused on division? How could we owe our Transcendent Discourse to a man so clearly uninterested in transcendence? “If there’s any coherent message to be gleaned from the hypocrisy whipped up by Hurricane Jeremiah,” Frank Rich put it this weekend, “it’s that this nation’s perennially promised candid conversation on race has yet to begin.”

That is an understatement. And the fact that it’s so is only partially the fault of the political press. There are, after all, two Jeremiah Wrights. There is Wright the political figure—Wright the corollary, and potential liability, to Barack Obama’s presidential campaign—and there is Wright the cultural figure, the community leader who speaks, if not for the African American community as a whole, at least for the subset of that community that is justifiably angered about historical injustices that are by no means yet consigned to history. In that sense, Wright represents a quandary for the media: Which identity, if either, is more worthy of coverage? Can the two even be disentangled? How, given the constraints of time and space and style inherent in news stories, do you convey one identity without slighting the other? How do you balance the high-level discourse of social-service journalism with the political discourse of daily reportage?

The media treatments of Wright have focused—nominally, at least—on the political Wright, on the reverend as both agent and victim of political controversy. And they are justified in this. The pastor’s immediate news value lies, after all, in the impact he has had, and will no doubt continue to have, on Barack Obama’s historic campaign for the presidency. As far as hard news goes, that role is where Wright’s import both begins and ends.

But from journalism’s wider role in our civic discourse—to the extent that journalists in the aggregate are charged not just with reporting hard news, but with filtering it and explaining it and finding meaning in it—there’s much more to be said about Wright than his now-severed relationship with candidate Obama. The conversation journalists were going to lead us in, the one that was going to start us on a new path to racial reconciliation—and such a conversation can certainly still be had—is rooted in Wright’s cultural identity. And engaging in it will require us to admit that the basic premise of Wright’s discourse is true: the American government has a shameful history when it comes to race.

There’s nothing radical about that. It is simply our past. And to articulate it is not to condemn the American experiment, but to admit that that experiment owes its success, in part, to the exploitation of people who were forced to take part in it. Which is obvious, of course—but it is also where the Wright coverage has gone astray.

Because rather than allow any truth at all to Wright’s claims—rather than admit that the reverend’s anger might be, at least in part, justified—the media instead literally wrote off the man who’d made them. His behavior, during the NAACP speech and the National Press Club Q&A session, was broadly deemed to be “defiant.” (Defiant of what?, one wonders.) Wright 2.0, per his media portrayal, is arrogant and cocky and narcissistic and limelight-loving and “wacky.” He is no longer, as he was in his previous caricature, merely “angry” and “incendiary”; he is now, apparently, just plain off his rocker. And per that portrayal, he has been exoticized and subtly mocked through images—like this one, from Reuters:

…and this one, from the New York Post:

…and this one, from The New York Times:

By personalizing the Wright narrative—by writing him off as Obama’s “crazy uncle,” by focusing on his “vanity” and his penchant for “performance”—the media coverage effectively delegitimized Wright as an agent of salient argumentation or even viable moral thought. His portrayal locates Wright in the pettiness of the personal rather than the fullness of cultural context. And it precludes conversation by taking Wright’s ideas and opinions and arguments and brushing them aside as the delusions of an unreliable narrator.

Which is, alas, nothing new. Consider the near-obsession with denouncing that has defined so much of the discourse during this election season—witness the many times, during the nominating contests, that a candidate has been forced to denounce/repudiate something one of his surrogates—or even someone only casually connected to his campaign—has said. Recall Hillary Clinton, without a hint of irony, asking Barack Obama not just to “reject,” but to “reject and denounce” the support of Louis Farrakhan during their L.A. debate. Recall when, after Geraldine Ferraro made her statements about Obama’s race, Clinton was herself made to “reject and repudiate” Ferraro’s statements—and the woman who had made them. Indeed, during the 2008 campaign—though it’s not limited, unfortunately, to the rhetoric of the campaign trail or, for that matter, to this year—the diction of healthy debate (challenge, disagree, argue, etc.) has been replaced by a cacaphonic chorus of language that would impugn debate itself:

Renounce! Denounce! Rebuke! Revile!

Condemn! Reject! Reprove! Disclaim!

Deny! Decry! Denigrate! Repudiate!

Even the editorial board of The New York Times—not a body known for dashing off emotional outbursts—subscribed to the rhetoric of renunciation: “This could not be handled by a speech about the complexities of modern life,” the board wrote in an editorial last week, daring Obama into action against Wright. “It required a powerful, unambiguous denunciation—and Mr. Obama gave it.”

When the editorial board of the country’s most powerful newspaper—by nature and by necessity one of the strongest advocates we have for a free and open marketplace of ideas—calls for denunciation (and “powerful, unambiguous denunciation” at that), that makes for a powerful and unambiguous annunciation about the marketplace itself. We’re talking, after all, about the language of McCarthy. Of Salem. Of Lenin. The language that assumes there is but one way to do things, and that those who would dare to claim otherwise deserve to be publicly pilloried, silenced, or, perhaps worst of all, ignored.

Whence controversy? Whence productive, provocative debate?

Which is not to say, of course, that Jeremiah Wright is a modern-day Cassandra, that to ignore him is to ignore—and, thus, deprive ourselves of—some kind of transcendent truth. While I think much of what Wright has been saying is truer than we have let ourselves admit out loud, there’s much of it that I disagree with. Vehemently.

But that’s beside the point. Wright’s is a story of race and politics and culture, to be sure, and of the connection among the three—but it is also a story about dissent, about the way we Americans, in this particular and perhaps even pivotal historical moment, treat ideas and opinions that don’t conform to the mainstream. Wright is openly challenging America’s most basic origin myth (the embrace of self-evident truths giving way to Liberty and Justice for all—virgin lands waiting to be populated by hardy immigrants who would risk their lives in the service of religious freedom). Yes, there was a war to win that Justice; yes, those virgin lands weren’t so virgin, after all; yes, those who came seeking Liberty won it by robbing other people of theirs. But most of the narratives we hear about America—not about the United States, the country, necessarily, but about “America,” the idea—are leavened, even today, with the assumption of Destiny. And with the assumption that the term “God bless America” is not a desire so much as a declaration of fact.

Wright flouts that assumption, openly and defiantly and, occasionally, literally. His sermons narrate history not through the lens (or the “hermeneutic,” as he likes to call it) of its victor, but from the perspective of those many and varied people who have been conscripted in freedom’s service—those victims of the means America justified by its lofty ends. (America is therefore the land of the future, Hegel wrote, where, in the ages that lie before us, the burden of the world’s history shall reveal itself.) Wright is not questioning the American dream, or even its citizens—he is not, like Pat Robertson or John Hagee or their ilk, questioning the personal behavior of individual Americans—but rather the actions of the American government.

And for that, he has been made a laughingstock. What we’ve seen in the Wright coverage wasn’t a dialogue, or even a deposition; it was a prosecution—one in which we all but pled insanity on the defendant’s behalf. The People vs. Jeremiah Wright, the “crazy uncle” versus Uncle Sam, made a mockery of the pastor in the press, all because—in addition to ministering to the poor in Chicago and serving as a spiritual guide to thousands—Wright had the temerity to question the actions of a government that has been, in kindest terms, imperfect. In a country so proud of its tradition of free speech, the narrowness of permission Wright’s treatment represents when it comes to our cultural discourse is profoundly ironic. As Mark Twain put it, “Irreverence is the champion of liberty and its one sure defense.” And in a nation whose founders deemed the questioning of government to be among the highest measures of patriotism, that irony is even deeper.

The founders, consigned to their historical moment as much as we are to ours, couldn’t have imagined today’s media—a beast whose tentacles stretch so far, whose influence is so pervasive in our lives and in our habits of thought, that we can hardly separate ourselves from it. (We can no more disown them than we can our own family.) Still, we can surmise that the men who valued above almost all else a down-and-dirty, full-throated debate—who believed that informed, open-minded, and passionate discourse was both the source and the gift of their hard-won freedom—would be fairly shocked at the current state of affairs. Wright’s only weapons, after all, are words and ideas, and these are only as powerful as we allow them to be. You have to wonder: what are we so afraid of?

Megan Garber is an assistant editor at the Nieman Journalism Lab at Harvard University. She was formerly a CJR staff writer.