Herewith, a trio of thoughts on the political-media story that won the day on February 1: Mitt Romney’s statement on CNN this morning that he’s focused on the middle class but “not concerned about the very poor,” because they have access to a “very ample safety net.”

Thought #1: We need a better typology of “gaffes”.

One of the media narratives that will be spun out of Romney’s comments is that he just can’t help putting his foot in his mouth. Here’s how Luke Johnson concluded his write-up of Romney’s remarks at The Huffington Post:

Romney’s statement is part of a pattern of previously poorly-phrased remarks that give his competitors fodder to call the former Bain Capital founder—who is worth between $190 million and $250 million—out of touch with the economic recession.

“Don’t try and stop the foreclosure process. Let it run its course and hit the bottom,” he said last October in Las Vegas, the hardest-hit metro area by the foreclosure crisis.

In January, Romney said, “I like being able to fire people who provide services to me” to explain why he favored competition among health insurers. “If someone doesn’t give me the good service I need, I want to say I am going to get somebody else to provide that service to me.”

But other than the potential for “fodder,” none of these things is really like the others. The furor around the “fire people” quote was, as Brendan Nyhan argued here at CJR, pretty much a pure media creation that depended on deliberately taking Romney’s words out of context. Romney’s “foreclosure” remarks, meanwhile, don’t seem “poorly-phrased” at all—they offered a succinct description of his policy. If his policy is unpopular with some voters, that has more to do with substance than word choice.

While, as in the “fire people” episode, there’s some artful truncating by the press at play here—the most common headline seemed to be something like, “Romney: ‘I’m not concerned about the very poor'”—Romney’s comments to CNN Wednesday morning are probably the best example of him undermining his policy position with his own infelicitous words. On the stump, he’s apparently in the habit of saying, “the people who need the help most are not the poor.” That’s a very debatable proposition, but it carries a different valence than a declaration that you’re “not concerned” about the poor.

Thought #2: Romney’s wrong about who benefits from the “safety net.”

Pressed by CNN’s Soledad O’Brien about his unconcern for the “very poor,” Romney said:

We have a very ample safety net, and we can talk about whether it needs to be strengthened or whether there are holes in it. But we have food stamps, we have Medicaid, we have housing vouchers, we have programs to help the poor. But the middle income Americans, they’re the folks that are really struggling right now, and they need someone that can help get this economy going for them.

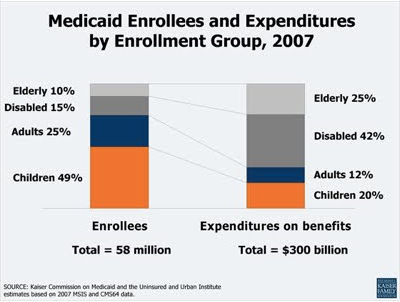

Set aside housing vouchers and food stamps for the moment, and focus on Medicaid. While it’s true that most Medicaid enrollees are children and adults in low-income households, most Medicaid funds cover long-term care for the elderly and disabled. This Kaiser Commission image published last April by Matt Yglesias tells the tale:

The upshot, as Yglesias wrote, is that many beneficiaries of Medicaid are actually families—middle-class families, and certainly families in that broad “90, 95 percent of Americans” that Romney says he’s concerned about—who would otherwise be stuck with the full tab for care for their elderly and disabled relatives. It’s debatable whether this is a wise arrangement, or whether it works as intended—for example, National Review’s Josh Barro has argued that affluent families game the system and should be paying more themselves. But what’s not debatable is that the universe of Medicaid beneficiaries extends well beyond the “very poor.”

Thought #3: CNN’s O’Brien asked some terrible questions, and not many good ones.

Perhaps Romney’s mistake was in trying to talk about his issue positions, when all O’Brien wanted to talk about was the horse race and hurt feelings.

Now, it goes without saying that part of an interview the morning after an important election, and during an ongoing campaign, will be devoted to horse race stuff.

But, still. O’Brien’s first question was about how Romney felt about his big win in Florida. When he replied that, obviously, he felt good, she asked—twice—how he would win over the party’s most conservative voters. Then she asked if Romney was offended that Newt Gingrich didn’t call to concede. Next, she asked if the negative tone of the campaign was costing him support among independents. Then she asked him—twice—if a protracted primary fight would hurt Romney in the general election. Then she asked if the tone of the campaign would continue to be negative. (Transcript here.)

Finally, she asked Romney how he plans to fix the fact that he “can’t connect with the people.” That’s what prompted his “not concerned about the very poor” line, uttered as Romney tried to show how he is concerned about the middle class. O’Brien, to her credit, followed up, and Romney fleshed out his answer. It would have been nice to have some further follow-up—see Thought #2 above—but they were out of time.

Even without Romney’s “gaffe,” this last exchange was by far the most substantive and newsworthy part of the interview, and it happened only because Romney took a question about a tiresome media preoccupation (whether candidates can “connect”) and used it to try to make a point about his policy priorities. If he’d actually been asked about those priorities, who knows what interesting things he might have said?

Greg Marx is an associate editor at CJR. Follow him on Twitter @gregamarx.