Two beliefs safely inhabit the canon of contemporary thinking about journalism. The first is that the internet is the most powerful force disrupting the news media. The second is that the internet and the communication and information tools it spawned, like YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook, are shifting power from governments to civil society and to individual bloggers, netizens, or “citizen journalists.”

It is hard to disagree with these two beliefs. Yet they obscure evidence that governments are having as much success as the internet in disrupting independent media and determining the information that reaches society. Moreover, in many poor countries or in those with autocratic regimes, government actions are more important than the internet in defining how information is produced and consumed, and by whom.

Illustrating this point is a curious fact: Censorship is flourishing in the information age. In theory, new technologies make it more difficult, and ultimately impossible, for governments to control the flow of information. Some have argued that the birth of the internet foreshadowed the death of censorship. In 1993, John Gilmore, an internet pioneer, told Time, “The Net interprets censorship as damage and routes around it.”

Governments went from spectators in the digital revolution to sophisticated early adopters of advanced technologies that allowed them to monitor journalists, and direct the flow of information.

Today, many governments are routing around the liberating effects of the internet. Like entrepreneurs, they are relying on innovation and imitation. In countries such as Hungary, Ecuador, Turkey, and Kenya, officials are mimicking autocracies like Russia, Iran, or China by redacting critical news and building state media brands. They are also creating more subtle tools to complement the blunt instruments of attacking journalists.

As a result, the internet’s promise of open access to independent and diverse sources of information is a reality mostly for the minority of humanity living in mature democracies.

How is this happening? As journalists, we’ve seen firsthand the transformative effects of the internet. It seems capable of redrafting any equation of power in which information is a variable, starting in newsrooms. But this, it turns out, is not a universal law. When we started to map examples of censorship, we were alarmed to find so many brazen cases in plain sight. But even more surprising is how much censorship is hidden. Its scope seems hard to appreciate for several reasons. First, some tools for controlling the media are masquerading as market disruptions. Second, in many places internet usage and censorship are rapidly expanding at the same time. Third, while the internet is viewed as a global phenomenon, censorship can seem a parochial or national issue–in other words, isolated. Evidence suggests otherwise.

In Venezuela, a case that we examine below in depth, all three of these factors are in play. Internet usage there is among the fastest-growing in the world, even as the government pursues an ambitious program of censorship. Many methods used by the state are beneath the waterline, and have surfaced in other countries. They include, as we and others have discovered, gaining influence over independent media by using shell companies and phantom buyers. According to Tamoa Calzadilla, until last year the investigations editor at Ultimas Noticias, Venezuela’s largest-circulation newspaper, the array of pressures on journalists in her country is not well understood in Europe or the United States. She resigned in protest after anonymous buyers took control of the paper, and a new editor demanded what she considered to be politically motivated changes in an investigative story about anti-government protests. “This is not your classic censorship, where they put a soldier in the door of the newspaper and assault the journalists,” Calzadilla told us. “Instead, they buy the newspaper, they sue the reporters and drag them into court, they eavesdrop on your communications and then broadcast them on state television. This is censorship for the 21st century.”

The new censorship has many practitioners, and increasingly refined practices:

• In Hungary, the government’s Media Authority has the power to collect detailed information about journalists as well as advertising and editorial content. Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s regime uses fines, taxes, and licensing to pressure critical media, and steers state advertising to friendly outlets. A comprehensive report by several global press freedom organizations concluded: “Hungary’s independent media today faces creeping strangulation.”

• In Pakistan, the state regulatory authority suspended the license of Geo TV, the most popular channel in the country, after a defamation claim against it was made by the intelligence services following a shooting of one of the station’s best-known journalists. The channel was off the air for 15 days starting in June 2014. Pakistani journalists say that self-censorship and bribery are rife.

• In Turkey, a recent amendment to the internet law gave the Telecommunications Directorate the authority to close any website or content “to protect national security and public order, as well as to prevent a crime.” President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been criticized for jailing dozens of journalists, and for using tax investigations and huge fines in retaliation for critical coverage (in 2009, for instance, tax authorities fined a leading media group $2.5 billion). More recently, the government blocked Twitter and other social media allegedly in response to a corruption scandal that implicated Erdogan and other senior officials.

• In Russia, President Vladimir Putin is remaking the media landscape in the government’s image. In 2014, multiple media outlets were blocked, shuttered, or saw their editorial line change overnight in response to government pressure. While launching its own media operations, the government approved legislation limiting foreign investment in Russian media. The measure took aim at publications like Vedomosti, a daily newspaper respected for its standards and independence and owned by three foreign media groups: Dow Jones, the Financial Times Group and Finland’s Sanoma.

Traditional censorship was basically an exercise of cut and paste. Government agents inspected the content of newspapers, magazines, books, movies, or news broadcasts, often prior to release, and suppressed or altered them so that only information judged acceptable would reach the public. For dictatorships, censorship meant that an uncooperative media outlet could be shut down or that unruly editors and journalists exiled, jailed, or murdered.

Starting in the early 1990s, when journalism went online, censorship followed. Filtering, blocking and hacking replaced scissors and black ink. Some governments barred access to Web pages they didn’t like, redirected users to sites that looked independent but which in fact they controlled, and influenced the conversation in chat rooms and discussion groups via the participation of trained functionaries. They directed anonymous hackers to vandalize the sites and blogs, and disrupt the internet presence of critics, defacing, or freezing their Facebook pages or Twitter accounts.

The biggest newspaper in Venezuela had changed hands, and questions about the origin of the funds and the identities of the new owners were met with silence.

Tech-savvy activists quickly found ways to protect themselves and evade digital censorship. For a while it looked like agile, hyperconnected, and decentralized networks of activists, journalists, and critics had the upper hand in a battle against centralized, hierarchal, and unwieldy government bureaucracies. But governments caught up. Many went from spectators in the digital revolution to sophisticated early adopters of advanced technologies that allowed them to monitor content, activists, and journalists, and direct the flow of information.

No place shows the contradictions of this contest on as grand a scale as China. The country with the most internet users and the fastest-growing connected population is also the world’s most ambitious censor. Of the three billion internet users in the world, 22 percent live in China (nearly 10 percent live in the US). The government maintains the “Great Firewall” to block unacceptable content, including foreign news sites. An estimated two million censors police the internet and the activities of users. Yet the BBC reports that a 2014 poll found that 76 percent of Chinese questioned said they felt free from government surveillance. This was the highest rate of the 17 countries polled.

The internet has allowed Chinese authorities to deploy censorship strategies that are subtle and harder for the public to see. In Hong Kong, where China is obligated by treaty to respect a free press, Beijing has used an array of measures to limit independent journalism, including selective violence against editors and the arrest of reporters. But it has also arranged the firing of critical reporters and columnists and the withdrawal of advertising by state and private sources, including multinationals, and launched cyberattacks on websites. The Hong Kong Journalists Association described 2014 as “the darkest for press freedom in several decades.”

National security policies place the US and other mature democracies in the same discussion as countries, like Russia, that see the internet as both a threat and a means of control.

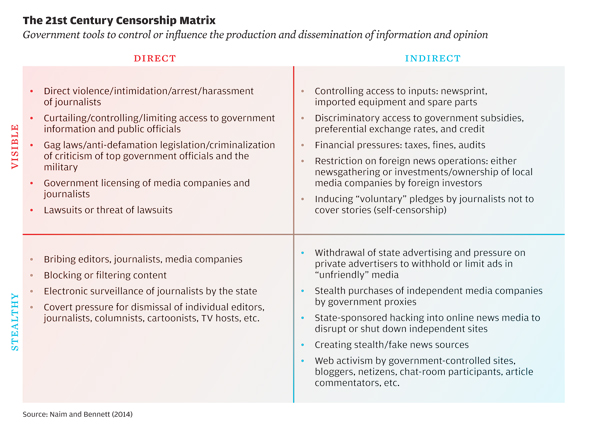

China’s actions demonstrate the emerging censorship menu: It can be direct and visible, or indirect and stealthy. These stealth strategies have become important as more governments try to hide their efforts to control the media. Stealth censorship can involve creating entities that look like private companies, or government-organized, non-governmental organizations, known as GONGOS. These organizations purport to represent civil society, but in practice are government agencies. The approach allows the anonymous hackers in Russia or China who attack the networks of critics at home, or governments abroad, to be portrayed as mysterious members of the sprawling global civil society, rather than allies of the regime.

Stealth censorship appeals to authoritarian governments that want to appear like democracies–or at least not like old-style dictatorships. And they have more options available to them than ever.

In illiberal democracies, how a government censors often reflects the tension between projecting an image of democracy and ruthlessly suppressing dissent. Some governments are trying to reconcile this contradiction by outsourcing censorship to groups they secretly control. Or they use currency controls to starve publishers of newsprint. Or they promote the migration of irritating journalists from major papers to online startups, where they have to build new audiences. This allows the government to keep a grip on the news media while concealing its fingerprints.

That is the story today in Venezuela. The country of 30 million has become a laboratory for testing ways to control the flow of news and information. As a case study in how governments disrupt independent media, the Venezuelan model offers several compelling ingredients: a feisty and courageous independent media, a press establishment serving elite audiences, a socialist revolution that claims to be building a popular democracy, and a deeply polarized citizenry that is witness to a near constant information war.

Recently, as a political and economic crisis has deepened, the state and its allies appear to have unveiled a new weapon: quieting critical reporting through the shadowy purchase of some of the private media companies most vexing to the government.

At first, the deals looked similar to the changing of the guard that is happening at old-line media institutions around the world. They have involved Venezuela’s best-selling but financially troubled newspaper, Ultimas Noticias, and its oldest daily, El Universal. But with time the sales seem less the result of market disruption, and more like political meddling using government-friendly buyers, dark money, and a web of foreign companies, some of them created overnight in order to conceal the identities of the new owners.

It is naive to assume there is a technological fix for governments that are determined to concentrate power and do whatever it takes to keep it.

The legal strategies used in the acquisitions make them hard to trace and evaluate. No evidence of a direct connection to government funds has surfaced. But the highly irregular structure of the deals, followed by changes in the editorial lines of the publications, have convinced journalists that their papers have lost their independence.

In the case of Ultimas Noticias and its parent chain, for instance, the buyer was Latam Media Holding, a shell company created in Curaçao less than a month before the sale, according to documents that we’ve examined. The price, which was not made public at the time, was at least $97 million, a huge sum for newspapers in Venezuela’s anemic economy. According to the documents, two days before the sale, one original shareholder sold her stock for $11 million to a Latin American currency fund of opaque ownership, a transaction not disclosed publicly. The biggest paper in the country had changed hands, and questions about the origin of the funds and the identities of the owners were met with silence.

The intrigue thickened when it was revealed that Latam Media Holding is controlled by Robert Hanson, a British businessman with no evident experience investing in media or in Latin America. Hanson is the multimillionaire son of the late British industrialist Lord Hanson, and a familiar figure in London society columns (the “raffish blade about town” in one memorable description in The Times of London). He has declined to talk about the purchase.

The new editors of Ultimas Noticias reassured the staff that the paper’s standards would not change. But within weeks, reporters say, they were told to soften pieces critical of the government or pressured not to write them at all, a charge the current editor has denied. Since the purchase, more than 50 journalists have resigned.

Journalists and media executives in Venezuela are used to rough treatment from authorities. The late President Hugo Chávez and his handpicked successor, the current President Nicolás Maduro, have attacked private news media for supporting the opposition and accused them of destabilizing the country. The government has passed legislation limiting press freedom, restricted access to public information, levied fines and taxes on media companies, withheld broadcast licenses, forced programs off the air, and used foreign currency controls to create a scarcity of newsprint, which is imported. At least a dozen newspapers have closed for lack of printing supplies.

The state has a long record of harassing, detaining, and beating reporters, and suing them for defamation. Officials routinely take to state media to excoriate individual reporters or news outlets. Reporters know they run high personal risks for writing about corruption or covering shortages of basic necessities, from toilet paper to medicine or food staples, in ways that reflect badly on the government. In a survey of journalists by the Venezuelan branch of the Institute for Press and Society, which supports press freedom, 42 percent reported being pressured by officials to change a story.

Cracking down directly on the media has proven costly to the government, sparking domestic protests and bringing international condemnation. And it has never worked for long. Until recently, Venezuelans could find vigorous coverage of such sensitive topics as Chávez’s health (he died of cancer in 2013), shocking crime statistics (the second-highest murder rate in the world), and state management of the energy sector (including the world’s largest oil reserves).

Then came the violent clashes between protesters and police during the first half of 2014. Students started the protests in response to a crime on a provincial campus, but they quickly grew into a full-blown crisis for Maduro. As the protests spread, and with them pictures of the dead and wounded, the government banned NTN24, an international cable channel covering the violence. It blocked all images on Twitter. Reporters, photographers, and camera operators were detained and beaten. State media scarcely covered the violence or the motives behind the protests. Particularly startling to some viewers was the lack of tough coverage on Globovision, a 24-hour news channel. It had been the last television station that was critical of the government. But several months earlier, it had been bought by an insurance firm reportedly close to the Maduro regime.

At Ultimas Noticias, the investigative team run by Tamoa Calzadilla obtained an electrifying scoop: a video showing police and men in civilian clothes firing on fleeing protesters, killing one. Despite the recent sale of the paper, Calzadilla and her team put the video online. Their report led to the first arrests of members of the security forces. But a short time later, the president of the chain that owns the newspaper resigned and was replaced by an ally of the ruling party.

The following month, Calzadilla presented the new editor with an inside look at the protesters and the police squaring off in Caracas. She says that he refused to run the piece unless it was changed to say that protesters were financed by the United States (there is no evidence of this). Instead, Calzadilla resigned, going into a bathroom in the newsroom and tweeting, “journalism first,” before exiting the building.

A month after the protests subsided last June, the owners of El Universal (whom Maduro had described on television as “rancid oligarchy”) announced that they had sold the 106-year-old daily.

If the purchase of Ultimas Noticias was mysterious, the sale of El Universal in July 2014 contained elements of farce. It was bought by a Spanish investment firm that had been founded a year earlier with an initial capital of about $4,000. According to documents published by the blogger Alek Boyd, the sole shareholder in the Spanish firm was a Panama-registered corporation called Tecnobreaks, Inc. But when Boyd contacted the founders of Tecnobreaks, a Venezuelan father and son apparently in the auto repair business, they said they had no idea of the sale and were not people of means. It was as if The New York Times had been bought by a Midas franchisee.

Months later, it is still a mystery who is behind the purchase of El Universal or how much they paid (estimates range from $20 million to $100 million). The Spanish firm remains the purchaser of record. But the impact on the journalism has been clear. In the month after the sale, at least 26 journalists said they were dismissed over critical coverage. Rayma Suprani, a popular editorial cartoonist, was fired for a cartoon that mocked Chávez’s famous signature, trailing off in a flat line, to depict the demise of healthcare in Venezuela. “We don’t know who bought El Universal or who pays the salaries,” she told CNN en Español after her dismissal. “But now we know they are bothered by the critical editorial line. So we can presume that it wasn’t some invisible man but the government got its hands on it.”

Suprani now posts her cartoons on Twitter, where she has more than half a million followers. Many of Venezuela’s most enterprising journalists have migrated online. Tamoa Calzadilla is now investigations editor of runrun.es, an independent news site with reporters in Caracas, where, she told us, “we are doing the journalism that needs to be done.” But while internet usage is growing sharply in Venezuela, less than half the population has access to the Web. In a country divided down the middle by politics, most Venezuelans are now getting half the story.

Despite the economic crisis, the government is investing aggressively to build its own media empire. State-owned Telesur has become the largest 24-hour television news channel in Latin America. Started by Chávez “to lead and promote the unification of the peoples of the SOUTH,” it now employs 800 reporters. The company reached a milestone last year with the launch of an English-language website and newscast, which it promoted in a full-page ad in The New Yorker.

For a moment in 2011, during the Arab spring, social media seemed to give democracy activists an advantage against entrenched regimes. As protesters triumphed in Egypt, Google executive and activist Wael Ghonim famously told Wolf Blitzer, “If you want to liberate a government, give them the internet.” Although the complex dynamics of the uprising went far beyond a “Facebook Revolution,” the term captured a sense that something important had changed.

Four years later, media freedom in Egypt is under withering assault. Dozens of journalists have been jailed, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. And last summer, Amnesty International reported having obtained internal documents that describe a government contract to build a system to spy on Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, and other social media.

This might be a slogan for the Facebook counter-revolution: To empower a government, give it the internet.

The Edward Snowden leaks made clear that the internet is a tool for peering into the lives of citizens, including journalists, for every government with the means to do so. Whether domestic spying in the United States or Great Britain qualifies as censorship is a matter of debate. But the Obama administration’s authorization of secret wiretaps of journalists and aggressive leak prosecutions has had a well-documented chilling effect on national-security reporting. At the very least, electronic snooping by the government means that no journalist reporting on secrets can promise in good conscience to guarantee a source anonymity.

National security policies place the US and other mature democracies in the same discussion with countries, like Russia, that see the internet as both a threat and a means of control. Most of these countries have not tried to hide from charges that they perform surveillance over the internet. Instead, Russia, India, Australia, and others have approved security legislation that writes the practice into law.

Journalists legitimately fear being swept up in this electronic dragnet. But frequently they are its specific targets. China has hacked foreign journalists’ email accounts, presumably to vacuum up their sources, and broke into the servers of leading US newspapers. The NSA hacked into Al Jazeera. The Colombian government spied on communications of foreign journalists covering peace talks with rebels. Ethiopia’s Information Network Security Agency has tracked journalists in the United States. Belarus, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Sudan all routinely monitor reporters’ communications, according to Reporters Without Borders.

Joel Simon, executive director of the Committee to Protect Journalists, describes the sinister consequences of surveillance in his recent book, The New Censorship. Simon recounts in chilling detail how Iran turned journalists’ reliance on the internet into a weapon against protesters in 2009. Security agents tortured journalists like Maziar Bahari (the subject of the Jon Stewart film Rosewater) until they divulged their social media and email passwords, and then combed through their networks, identifying and arresting sources. Iranian officials also created fake Facebook accounts to lure activists. “The use of Facebook and other social media platforms by governments to dismantle political networks has become a standard practice,” Simon writes.

It’s not only states that are using these techniques. In Mexico, drug cartels run grotesque online media operations to intimidate rivals, the government, and the public. They have viciously silenced efforts to report anonymously on their activities on social media. In October 2014, cartel members kidnapped a citizen journalist in Reynosa, Maria del Rosario Fuentes Rubio, and then posted pictures of her dead body on her Twitter account.

It is little wonder why governments would pursue a strategy of weakening print and broadcast companies if it meant journalists moved to a platform the state can control and monitor. In Russia and elsewhere, there is a pattern of independent media being pressured not just by markets but by the state to move online, where they must rebuild their audience and the state is a powerful tenant, if not the landlord. If independent media grow too big online, like the popular Russian news site Lenta.ru, they can see their editors suddenly dismissed, the editorial line changed, and the site crumble.

One disturbing trend is the banding together of governments to create an internet that is easier to police. China has advised Iran on how to build a self-contained “Halal” internet. Beijing has also been sharing know-how with Zambia to block critical Web content, according to Reporters Without Borders. Private surveillance firms advertise their wares to countries that want to upgrade their encryption penetrating software.

If that is not enough, some governments can still count on self-censorship to do the work for them. Last October, after a deadly attack on the army by Islamic militants, top editors at more than a dozen Egyptian newspapers pledged to withhold criticism of the government and block “attempts to doubt state institutions or insult the army or police or judiciary.” The ownership of Al Nahar television added: “Freedom of expression cannot ever justify belittling the Egyptian Army’s morale.”

For every government that succeeds in controlling the free flow of information or repressing journalists, there is a counterexample. Courageous citizens have found ways to circumvent or undermine official controls. Or they are willing simply to risk opposing a government’s claims that it has the sole authority to write history. This power struggle is far from over, and its outcome will vary among countries and over time. Technological innovation will create new options that enable individuals and organizations to counteract government censorship, even as governments adopt technologies that enhance their ability to censor.

Pressures on governments for transparency, accountability, access to public information, and more citizen participation in public decisions will not go away. Autocratic states face populations that are more politically awake, restless, and harder to silence. Ukrainians showed recently that citizens fed up with the way they are governed could topple a president, even if he has the support of neighboring Russia. Or in Hong Kong, as the world witnessed last fall, a leaderless group of activists can defy China’s immense power.

But states retain extraordinary capacities to alter the flow of information to suit their interests. And a growing number of governments are undermining the checks and balances that constrain chief executives. From Russia to Turkey, Hungary to Bolivia, leaders are packing Supreme Courts and the judiciary with loyalists and staging elections that reward their allies. They are weakening the institutions that exist to prevent the concentration of power. In such a political environment, independent media cannot survive for long.

The internet can redistribute power. But it is naïve to assume that there is a simple technological fix for governments and their leaders who are determined to concentrate power and do whatever it takes to keep it. Censorship will rise and fall as technological innovation and the hunger for freedom clash with governments bent on controlling their citizens, starting with what they read, watch, and hear.

Eduardo Marenco provided research assistance on this piece.

Philip Bennett and Moises Naim Philip Bennett is director of the DeWitt Wallace Center for Media and Democracy and a professor at the Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke. He is a former managing editor of The Washington Post and of Frontline. Moises Naim is a distinguished fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a syndicated columnist, and a contributing editor at The Atlantic. He was editor in chief of Foreign Policy from 1996-2010.