I’ve always regretted that I never thanked Goldie Hawn for launching my career as a publicist. Goldie became my client when I was hired as an account executive at PMK in 1981, a movie PR firm in New York. (It is now called Pmk*Bnc.) I knew I didn’t want this job and had already turned it down when my friend Anne took me to lunch. I’d set up a few interviews by that point in my life, but publicity was only a fraction of my professional and personal activities, which ranged from designing posters to composing music. In fact, at lunch I handed Anne my Walkman so she could hear some music I had written for the soundtrack of a Super-8 Adam Brooks feature called Ghost Sisters (the cinematographer was Jonathan Demme!). And yet she somehow talked me into taking her spot in this obvious hornet’s nest. She said that this job would give me “power.” I truly had no idea what that meant.

Anne was the New York contact for Hawn and Lindsay Crouse (an actress I loved). Anne took me to Circle Rep, where Crouse was appearing in a production of Childe Byron opposite William Hurt. Hurt introduced himself to me, as did John Lithgow, who had come to see the play. Maybe what Anne meant by “power” was that people I was in awe of would come over and say hello to me? Crouse was married to David Mamet, and later that night, it was the same deal—David Mamet giving me a firm handshake and saying, “David Mamet.” Like I hadn’t seen his plays and read every fricking word he’d written. Years later, I would rep three of his movies.

All this was cool, except I had no clue how to do the job. My little coffin room in the PMK office had a great view of the city that Anne had probably enjoyed, but when I got there they were building a skyscraper a few floors down that within a few weeks walled in my view. Down the hall were the more palatial offices of Peggy Siegal and Harriet Blacker and, at the other end, in a junior suite like mine, Catherine Olim—now a powerhouse publicist but who then had only just been promoted. Everybody had an assistant whom presumably they had hired and could fire, but I was stuck with Anne’s assistant, a voluptuous young woman whose golden globes were always peeking out of blouses that would have made Jessica Rabbit blush. She was extremely popular with the men on the client list, which made her far more important to the company than I was, even if I had been able to do my job, which I wasn’t.

Before this, I had worked for a small but prestigious distributor of foreign movies called New Yorker Films. I was hired because I had some graphic-design skills, and the ultra-cheap boss Dan Talbot realized that I could do their posters and catalogs in addition to threading projectors and filing. When I was hired, he said that I was going to have to work with the critics. As he saw my face light up at the prospect, he looked at me with pity. If you loved foreign cinema, New Yorker Films was a surreal place to be: It was a “Bertolucci on Line One” kind of place; it was a “pick up Fassbinder at the airport” kind of place. I set up press for Isabelle Huppert, Gerard Depardieu, Fassbinder bombshell Hanna Schygulla, and directors like Claude Chabrol, Werner Herzog, Joseph Losey, and Eric Rohmer. I had no idea how to manage publicity. All I did was show the films, which were really good. Editors came and requested interviews, and I made the arrangements. This kind of experience hardly qualified me to work at PMK.

The actual “power” at PMK rested in the partners, who all worked in LA: Pat Kingsley, Michael Maslansky, and Neil Koenigsberg. Michael and Neil came often to the office for meetings, but Pat never did during the short time I worked there. She was the one who signed and handled Goldie Hawn and Lindsay Crouse. Hawn was red-hot at the time, having just broken out with Private Benjamin. When the media wanted to interview her, they called Bill Murray of Celebrity Service (no, not that Bill Murray) and asked who Hawn’s New York contact was; Bill would give them my number. I would call Pat up, my voice chirpy with excitement, and say, “The Sunday New York Times wants to do Goldie!” and she would cut me off and say that no, Goldie didn’t have a movie coming out and there was nothing to sell. This was something I’d never heard before. The purpose of media coverage is to fulfill our client’s needs?

I quickly figured out how the game was played: We had a bucketful of stars and a reasonable number of superstars, and anybody who wanted to regularly fill a magazine cover had to cross swords with us (or people like us) or head back to their previous job at Weekly Reader. We made our biggest clients available only when we wanted to, and making them inaccessible increased their allure. Pat also served our clients by offering the kind of sage advice that prevented publicity debacles (indeed, milliseconds after Tom Cruise fired Kingsley, he was mid-flight over Oprah’s settee). When disaster did strike, we were around to sweep up the mess with blandly manicured statements, Clintonesque dodgeball, and even the truth, if it was expedient.

The majority of what we did at this publicity firm was to strategically turn down most of the requests for our clients. Still, the relationship that agency publicists had with the media in those days was generally congenial. If you are booking The David Letterman Show, you know who is right for the show, and so does a first-rate publicist; in fact, it wasn’t unusual for publicists to move over to top jobs in the media, and vice versa. The greatest misunderstandings were with publicity executives at some studios and distribution companies who pursued one-size-fits-all approaches to publicity, unlike our more strategic method. For each release, they created a phone-book-sized memo to show their superiors that every media outlet had been approached, and no stone had been left unturned. These documents are chock-a-block with hilarious boilerplate comments like “Claire promises to watch her screener soon,” or “left several messages for Bernie,” or my favorite, “Sarah is thinking it over,” which usually means, “no, but I don’t want to tell you that yet.” After such time-consuming mishegas, the studio publicists were bewildered and stressed when they secured assignments and then the mean old personal publicists turned them all down.

Simply passing requests for Goldie Hawn to Pat Kingsley imbued me with a synthetic muscularity that lured top editors and talk-show bookers into my clutches. Once I had them on the phone, I’d ask if they’d seen the side-splitting new comedy Under the Rainbow, starring Chevy Chase, Carrie Fisher, and Billy Barty. As I said this, I felt like I had eaten a 50-pound bag of snot. Actually, I always felt like this. I was a midwestern rube who had fallen down a wormhole into an alien world I found shockingly cynical. I lacked the skills and emotional constitution for the job, and this caused me to be fearful and make mistakes. At the same time, I didn’t want to be the kind of loser who quit after a few days, so I chose to be the kind of loser who accepts that every day will be a living hell.

It seemed that I was now a publicist, so I decided to do what I had done in previous self-reinventions—I was going to find out what a publicist was and try to turn myself into one. I would still hate my life, but I would be incredible at my job, dazzling them with my encyclopedic knowledge of international cinema, and everyone would admire me. Of the three PMK partners, I was most drawn to Kingsley—she was just so damn smart. I loved listening to her consider the pros and cons of every decision. In publicity, you can’t do everything. Editors see other outlets as their competitors: It’s Vogue or Elle; it’s New York or New Yorker or The New York Times Magazine. What is right for a particular movie or client? Pat was also a chess player—she didn’t think about what her client should do for just one movie, but also looked to the years ahead. If the client does a media blitz now, what is left for that personal project going into production next year? Nowadays, you can find dozens of young publicists who know how to say “no”—“no” is easy—but knowing when to say “yes” requires experience, wisdom, and in the case of Pat, a certain don’t-f*ck-with-me confidence that she could control the story. So, Goal No. 1 in my publicity education: Grow a brain, learn everything there is to know about the media, and try to become, in my own way, like Kingsley.

Teacher No. 2, Peggy Siegal, was not the kind of person I would socialize with, but she was extraordinary at her work, and was very generous at sharing her expertise with me. Peggy was unstoppable; if she was onto a story, and say there was something in her way—say, Chicago—well, you’d just have to move Chicago. So I told myself that I would strive to become as relentless as Peggy, and when necessary, as impregnable as a titanium ingot.

Back in my days at New Yorker Films, I had encountered a guy named John Springer. He had represented Marilyn Monroe, Taylor and Burton, Bette Davis, Joan Crawford, Henry Fonda, Gary Cooper, Montgomery Clift, Walt Disney, and other legends. Springer embodied class: He was an impeccably dressed, highly cultured, and modest man. Trying to match John in the elegance department was a preposterous notion, but I decided it was essential that I get the kind of pedigree that comes from a high-quality client list.

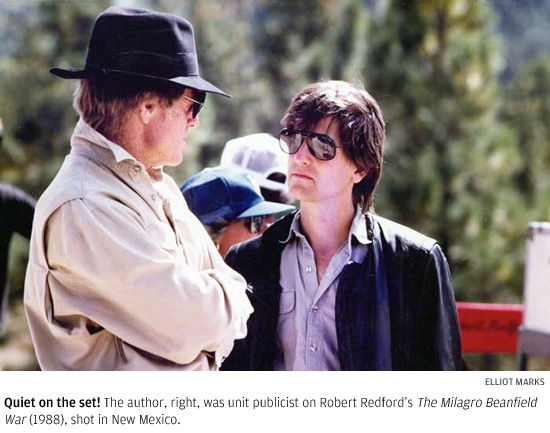

I met Lois Smith when she hung out a shingle with Peggy Siegal, post-PMK. (Lois died, I’m sorry to say, just as this article was going to press.) Lois was the longtime publicist to Robert Redford, which is how I got to know him. She was given to greeting all and sundry with “Hello, ducks!” If you were escorting her through the back alleys of a movie set, she’d say, “Lead on, MacDuff!” That would have been enough for me to love Lois, but there was much more. Once one of Lois’s clients was involved in a messy divorce, and Lois had to face the cameras. Sitting at home, watching it on TV, I teared up, thinking if I ever got in a jam, I would want somebody as humane and calm and wryly funny to shield me from the slings and arrows of the media. My longtime client Errol Morris told me that when he looked for a lawyer, he wanted somebody he would pay by heaving ten pounds of raw meat over a fence, but I knew that if I was in a mess, I would want somebody like Lois at my back—a straight shooter who could kill with kindness and charm instead of a stiletto. Lois would become my numero-uno role model.

The press agent’s reason for being is the art of persuasion, and there are as many ways to practice persuasion as there are human beings. It was my belief—and it still is—that few do it well, and I studied the best to find the way that suited me. Over time, I discovered that I was willing to turn down business (hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth, as it turned out) if it involved movies I didn’t personally like. Not that I was noble; I simply couldn’t, for the life of me, figure out how that would work—calling a journalist I respected and saying that a piece of crap was good? I would have enjoyed spending the money, but what would happen the next time I called? Of course I did like a lot of movies that the media hated, but if somebody got a call from me over the decades, they had a reasonable expectation that I might be calling about something decent. At PMK, I worked on a lot of great movies, but there were many occasions when I had to fib, and I didn’t like the unpleasant taste it left in my mouth. After I was fired at PMK, I went back to my apartment and in no time, people were calling me to represent films. Having been schooled at PMK, I was ready.

Since I was a small child, I have worshiped actors and movies, and when I got older, filmmakers. It has been a great honor to have helped them in any way. As I look back over my career, I realize how much this work has given me and how lucky I have been to have fallen into it. Being a publicist has taken me all over the world and allowed me to hang out with a lot of fascinating people, and it’s given me a fly-on-the-wall look at the world of fame and celebrity that very few people have. Journalists always think they know more than I do, but they never get to see what happens after their interview is over and they leave the hotel room.

The big secret of celebrity isn’t that some famous people are meaner than the rest of us—although pampering does spoil you—it’s that they are more likely to be unhappy. Maybe it’s because insecurity and hurt fueled their drive to get famous, and when they get up the hill, they realize it hasn’t solved any of their problems and the only way to go from that point is down. Then again, if they have pursued acting or directing purely for the love of it, rather than the desire to get famous, celebrity is generally as wonderful as you’d imagine it would be, with some occasional nuisances, like the paparazzi and annoying fans. Singer-actor Ruben Blades once told me, “Power doesn’t corrupt—it reveals,” and that’s what I’ve seen my whole life. Many people take the opportunity that success provides to crack up or die with greater velocity than those of us who have never been profiled by People. No matter how hard you try, some people just won’t allow you to help them.

The biggest irony of my life is that I am against the idea that artists should have to do publicity. If we lived in a world in which people could discover movies without publicity, I think it would be a better world. The thing I love about movies in particular and art in general is that they contain things that are ineffable, and journalists want to ruin it by demanding that everything be explained, down to the tiniest detail. When asked by someone I trusted, I always advised them to treat the interview as a performance in which many words are spoken but nothing is ever given away. I’m not suggesting “talking points,” because that is a very tedious way to get through a publicity junket. No, you have to be actively open and alive to the process of holding onto the mystery: That is the most essential thing an artist can ever possess, infinitely more precious than fame.

Postscript: You may have noticed that I haven’t explained why I never thanked Goldie Hawn for all she did for me. The reason is that I’ve never spoken to her, and have only seen her on Laugh-In and in her movies. Still, let me offer this article as a token of my heartfelt gratitude.

Reid Rosefelt currently coaches filmmakers in Facebook and social media marketing. His publicity credits include Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Stranger Than Paradise, Desperately Seeking Susan, High Art, All About My Mother, Central Station, Pollock, and Precious. His personal clients have included Errol Morris, Ally Sheedy, Harvey Keitel, Cynthia Nixon, IFC, and the Sundance Institute.