In December, Ohio State University suspended five of its football players for violating the rules governing intercollegiate athletics by exchanging their Buckeye memorabilia for various forms of payment, including the handiwork of a local Columbus tattoo parlor. Over the next few months, the digging of media outlets near and far pried open a capacious vault of misdeeds: the “gear scheme,” as it came to be called, involved not just a few players during a single season, but dozens of players over the better part of a decade; in that time, a number of scholarship athletes had also received sweetheart deals at a local auto outlet; and head coach Jim Tressel had hidden incriminating evidence of these transgressions from his superiors for more than eight months.

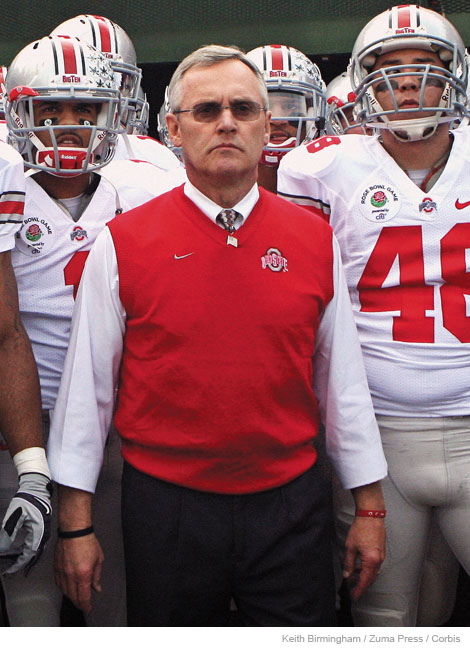

Punishment ensued. Ohio State, a perennial power in college football for more than half a century, forfeited its entire 2010 Sugar Bowl championship season; Tressel, regarded by many as a paragon of coaching integrity, was forced to resign; and Terrelle Pryor, the team’s star quarterback who was at the center of the scandal, abruptly left school to try his luck in the National Football League.

In many ways, the chaos in Columbus is just the latest in a seemingly endless series of scandals in big-time college sports. Over the last three decades, investigative sports reporters have excavated dozens of episodes of rule-breaking in football and men’s basketball programs, from Southern Methodist University’s “Ponygate” affair in the 1980s to the pay-for-play shenanigans at the University of Washington in the 1990s to agent tampering at the University of Southern California in the aughts. As this issue went to press, Yahoo Sports blew the lid off the latest installment, at the University of Miami, which, based on initial reports, may eclipse all other scandals in terms of scale and audacity. Off-field trouble, once a side project of the beat, has become the defining story of college athletics. Anyone who doubts it need only scan the header of espn.com’s homepage, which on many days reads like the abstract of a criminal indictment.

The cumulative reportage of a relatively small group of sports journalists on what might be called the Scandal Beat constitutes a compelling case for the unenforceability of the NCAA’s bylaws. In the process of building that case, these reporters have delivered an impressive perp walk of bogeymen: scurrilous agents, meddling boosters, selfish teenage athletes, badly behaved coaches. In many ways it has been a wildly successful display of watchdog journalism, and it helped establish the idea that sports is something that can and should be subjected to the same journalistic scrutiny as other institutions in our society—and that the sports desk could be more than just the “Toy Department,” as it had been derisively tagged by newsroom colleagues.

But the success of this work also belies a deeper problem with the coverage of college sports. The Scandal Beat exists as a kind of closed loop: a report of rules violations, an investigation, sanctions, dismissals, vows to do better, and then on to the next case of corruption where the cycle is repeated. The reporting, intentionally or not, promotes the idea that the corruption that plagues the NCAA is the problem, rather than merely a symptom of a system that is fundamentally broken. The Scandal Beat, with its drama and spectacular falls from grace, is much less adept at managing the next step: a robust discussion, prominently and persistently conducted, of why these scandals keep happening and what can be done to prevent them.

Despite its familiar feel, the OSU implosion seemed to represent a significant milepost in the national conversation about big-time college sports—if not a moment of truth, then at least a moment for truth. The fact that the conflagration had claimed a member of college football royalty, combined with the contemporaneous cascade of other scandals—including those that currently smolder at Auburn, Oregon, Boise State, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Oklahoma—appears to have opened the door to the possibility of finally starting that deeper discussion. In August, a summit of university leaders, convened by NCAA President Mark Emmert, agreed to raise educational standards for incoming freshmen and streamline the association’s bloated rule book. Summit participants vowed to address in the coming months the issue of athletes’ financial needs, but Emmert reiterated his opposition to paying students. Meanwhile, a class-action lawsuit filed against the NCAA by former UCLA basketball star Ed O’Bannon, which challenges the non-compensation of college athletes, is slated to go to trial in early 2013.

The sports commentariat has begun to question, more frequently and volubly, the very foundation of amateurism and higher education that the stakeholders in big-time college sports cling to. And even some of the stakeholders themselves are easing their grip: Mike Slive, the commissioner of the Southeastern Conference, which is widely considered to be the dominant football conference in the country, has advocated providing additional financial support for athletes, and in July confessed that the scandal headlines had cost major college sports the “benefit of the doubt.”

This moment may come to nothing. Given the NCAA’s history of fecklessness and the powerful financial interests aligned with the status quo, meaningful reform will be difficult. But it raises an interesting question for the future of sports coverage: Is the Scandal Beat, with its singular focus on busting rule-breakers, paving the way to reform or helping to block the way?

Sharecropper Economy

Even at its most righteous, college athletics—and I’m referring here to the so-called revenue sports, football and men’s basketball—is a multibillion-dollar enterprise based on an exploitive business model. Universities get gobs of money that helps float their entire athletic departments, and coaches and administrators are paid handsome salaries, all from the talent and effort of an essentially unpaid labor force of young athletes.

The NCAA’s 346 biggest athletic departments, which are classified as Division I, took in combined revenue of $8.7 billion last year. Ohio State’s budget alone topped $100 million; and Jim Tressel, prior to his resignation, was earning an annual salary of roughly $3.5 million. (It’s worth noting that Tressel was only the sixth-highest-paid college football coach in 2010; Alabama’s Nick Saban topped the list at $6 million.)

Meanwhile, the “compensation” for OSU’s football players, like all collegiate athletes, tops out at tuition, room, and board—but only for those on scholarship. This fact—that the kids get at least a shot at a free college degree—is what defenders of the system lean on when the matter of exploitation comes up. But even allowing for improved average graduation rates (which the NCAA trumpeted last year despite decidedly mixed results, especially at the more prominent sports schools), the idea that meaningful education is behind all of those diplomas is at least debatable, when one considers the number of “general studies” degrees and the evidence—turned up by the Scandal Beat—that classwork is not always handled by the athletes alone.

In any event, these “student-athletes” are prevented from earning any additional money that might be construed as related to their role as an athlete. Schools can sell the players’ jerseys and other memorabilia at stadium gift shops, they can put the players on billboards, feature them in television ads, and trot them out to impress the boosters, all without a dime going into the athletes’ pockets. In March, HBO’s “Real Sports” did the math and found that under the revenue-sharing model used by the NFL and National Basketball Association, where players get 57 percent of league revenues, members of the University of Texas’s 2009 football team were each worth $630,000 while those of last year’s national champion Duke University men’s basketball team were worth $1.2 million each. A USA Today story that same month calculated the median annual cost of an athlete’s grant-in-aid package: $27,923, a relative pittance.

It is a disjuncture of the market value that begs to be disobeyed, a fact that isn’t lost on the Scandal Beat reporters. “I once heard athletes described as sharecroppers, and I always thought that was pretty accurate,” says Charles Robinson, the senior investigative reporter for Yahoo Sports who has had a hand in breaking some of the biggest corruption scandals in recent years, including the latest out of Miami.

Robinson and his colleagues have captured the surface consequences of this perverse economy (the rampant cheating), but their work also has atomized a story fundamentally about economics into an endless cat-and-mouse game of rules violations.

Rise of the Scandal Beat

Reporters first began to seriously grapple with the chicanery in college sports in the 1940s, when a point-shaving scandal that began with City College of New York spread to six other universities. “Big-time college basketball, the commercialized, Madison Square Garden variety, got another brutal kick in the teeth,” read a Time magazine story from 1951, “the worst yet, in a game already punchy from its own scandals.”

In the 1960s, Jack Scott, a former Stanford sprinter who became athletic director at Oberlin College, set out to save college sports by crusading against its over-commercialization and over-authoritarian coaching culture. “Scott really gave voice to a lot of the ills underlying a lot of this stuff and he did it in a very smart and organized way,” says Sandy Padwe, who served two stints as Sports Illustrated’s senior editor in charge of investigations from the late 1970s to the mid-1990s. “Slowly, but surely, people began to realize that the only way to get at the root of this problem was do it investigatively.”

But it was in the 1980s that college sports ballooned into the sprawling, hype-besotted business we know today—and, not coincidentally, when the Scandal Beat really took root. A 1984 Supreme Court decision ruled that the NCAA’s television plan—which limited the number of televised football games and the opportunities for schools to negotiate their own terms—violated the Sherman Antitrust Act, paving the way for the explosion of modern college football broadcasting. In 1982, CBS began exclusively broadcasting the NCAA Men’s Basketball Tournament, at a price of $16 million a season (it grew to $55 million by 1988). Last year, the NCAA grossed $680 million from fees on television and marketing rights.

As the money in the newly corporatized college sports world soared, and the NCAA’s rule book grew fatter and more nitpicky, so too did the incentives to break the rules. A post-Watergate zeal in the nation’s newsrooms and the failure of the NCAA’s enforcement arm to keep pace further crystallized the mission of the Scandal Beat. “College sports was fertile ground,” says Armen Keteyian, a former investigative reporter for Sports Illustrated who is now the chief investigative correspondent for CBS News. “It was like a hundred-to-one in terms of scandals to the number of NCAA investigators. They were naïve, and they didn’t have the depth of knowledge to do these kinds of investigations.”

Journalism did, however, and a handful of investigative pioneers on the sports desk built the template for the Scandal Beat, establishing the methods (hanging around parking lots to find out what cars athletes drove, for instance), the patois (“in violation of NCAA rules”), and the general disposition of the scrutiny. The work, done with great ingenuity and often at great risk—reporters faced death threats while their employers endured lawsuits and subscription cancellations— won its journalistic stripes. Within the decade, two mid-sized newspapers would win Pulitzers for their investigations of athletic departments: The Arizona Daily Star in 1981 and the Lexington (Kentucky) Herald Leader in 1986.

Still, one of the salient points of Jack Scott’s “radical athleticism” movement begun a generation earlier, that the rule-breaking that plagued college sports is intrinsically tied to the commercialization of the enterprise, tended over time to get lost in the cataclysm of corruption that toppled heroes and humbled great universities. “We operated under, ‘Here are the rules and if people are breaking those rules we’re going to report on that,’” says Elliott Almond, an investigative sports reporter for the Los Angeles Times back then who now covers Stanford for the San Jose Mercury News. “We were never entirely reflective.”

The Coach Killer

George Dohrmann’s career provides an instructive illustration of the Scandal Beat’s allure as well as its limitations. Dohrmann, a senior writer for Sports Illustrated, started in 1996 as a part-timer answering phones on the Los Angeles Times’s sports investigative desk. Among his first story assignments was to co-author a series that explored the matrix of conflicted interests that suffuse elite amateur basketball in talent-rich Southern California.

While doing those stories, Dohrmann got a tip that Baron Davis, a highly-rated point guard who had recently committed to play at UCLA, was driving around in a suspicious car. Dohrmann went to Davis’s high school to poke around, where he spotted Davis pulling out of a parking lot in a black 1991 Chevy Blazer. As Dohrmann soon reported, the Blazer originally belonged UCLA coach Jim Harrick, who sold it to Davis’s sister two days after Davis signed his letter of intent with the school. Despite what seemed a clear violation of NCAA rules, the Pac-10 Conference (now the Pac-12), of which UCLA is a member, failed to find any wrongdoing on the part of the coach or the school, ultimately accepting their contorted explanation of how the transaction was aboveboard.

“That shaped everything that I have come to understand about how the NCAA works,” says Dohrmann. “We found something that anybody with healthy common sense would say was a quid pro quo and the school managed to explain it away.”

Nevertheless, a month later, Harrick was fired. The official explanation was that he had falsified expense reports to obscure the fact he had taken recruits out for dinner, but it is hard to believe that Dohrmann’s revelations had nothing to do with the decision.

Not long after, Dohrmann left the Times to cover the University of Minnesota for the St. Paul Pioneer Press. “You walk in and you assume that the school is cheating,” he says, describing his mindset at the time. In 1999, Dohrmann, then just twenty-six, found the dirt in the Golden Gophers’ athletic department, reporting a series of stories that detailed an academic fraud operation in the men’s basketball program. The revelations won Dohrmann a Pulitzer, and a job at Sports Illustrated, while the school was hit with serious sanctions and its coach, Clem Haskins, received a seven-year ban.

Ohio State’s Jim Tressel would be Dohrmann’s third scalp, though he had more than a little help in taking it.

In March of this year, three months after the press conference announcing the player suspensions at OSU, Yahoo’s Charles Robinson and Dan Wetzel broke the story that Tressel had known for months about the gear swapping by members of his team. This touched off a feeding frenzy by other outlets, notably the Columbus Dispatch, ESPN, and the OSU student newspaper, The Lantern.

By April, Dohrmann had become convinced that no other reporter was pushing the tattoo parlor angle far enough, so he flew to Columbus and began asking questions. On May 27, a Friday, Dohrmann phoned Ohio State with the allegations his reporting had turned up: that, going back to 2002, significantly more players than had been reported had traded memorabilia for tattoos, including nine who were currently on the team. On Sunday, the university responded to Dohrmann with a statement from athletic director Gene Smith that distanced the school from Tressel. The next day, Tressel resigned.

Dohrmann’s scoop earned him plaudits from the sports journalism community at large, but there were detractors. Deadspin’s Tommy Craggs and Fox Sports’s Jason Whitlock, both outspoken critics of the NCAA generally—Craggs has prophesied its ultimate demise—and of the Scandal Beat specifically, publicly attacked the SI exposé. Whitlock, fomenting on Twitter, called it a “typical slave-catcher investigation,” and mocked what he perceived to be Dohrmann’s and Sports Illustrated’s efforts to take credit for Tressel’s firing. Craggs, in a blog post, said Dohrmann represented a “passel of excellent journalists” who had “turned themselves once again into mall cops for the NCAA.”

Dohrmann doesn’t see it quite that way. “If he means we go get things the NCAA’s enforcement staff doesn’t, he is correct,” Dohrmann says. “If he feels that we are doing the NCAA’s job, this would be like saying The New York Times is the Justice Department’s mall cop.”

Still, Dohrmann has his own misgivings about the Scandal Beat. “Of course the NCAA can change and it does change slightly, and stories that show wrongdoing force small changes,” he says. “Now, every compliance arm in the country is dealing with tattoos. When I wrote about academic fraud in Minnesota, I am sure every school in the country tightened up its academic counseling department. Small changes occur because of the scandal. Are there macro changes, like paying athletes, because enough of these scandals get broken? It is possible. I just have no faith.”

Beyond the Scandal Beat

The paradox that Dohrmann describes—he both defends the work and acknowledges its limitations in getting at the underlying problems—came up time and again in my conversations with Scandal Beat writers.

Rick Telander, the Chicago Sun-Times sports columnist whose 1989 book, The Hundred Yard Lie, argued that big-time college football should remove its threadbare veil of amateurism, puts a finer point on the discrepancy, calling the rules violations the “crumbs of the problem.” He says: “The big muffin is right in front of us every day. We know it and accept it, so that’s where all the craziness starts. We accept the Big Lie, so we are dazzled and amazed by the little lies. I have found that completely self-defeating and really it hasn’t changed.”

In this way, the Scandal Beat sets its own trap. It produces important stories that fit into a celebrated tradition of muckraking and watchdog reporting. They are the kinds of stories that win prizes and generate traffic. Most of the reporters who do them have been reared in an industry whose professional code demands “objectivity,” a sort of bloodless presentation of the facts that, at its worst, can reduce an obvious injustice to a he said, she said cop-out. The result is straightforward coverage of the NCAA and its rules—and the inevitable violations of those rules—rather than coverage that challenges the validity of the rules themselves, and the system that upholds them.

There are journalistic efforts to come at the ills of college athletics from the less sensational but potentially more fruitful direction of economic justice. For about five years, the Indianapolis Star’s investigative reporter Mark Alesia covered the NCAA, which is based in Indianapolis, as a quasi-beat, tailoring his focus to the underlying economic issues, as opposed to matters of enforcement. In 2006, he wrote a series of stories that scrutinized the astounding fact that less than 1 percent of the NCAA’s athletes produce more than 90 percent of its revenue.

In 2008, Alesia moved to a news-side investigative beat and his work on the NCAA largely ended. These days, only USA Today follows the money of college sports as a matter of practice, annually updating a database of head coach salaries and athletic department budgets. The newspaper’s reporters mine the data for stories that probe the commerce of college sports. Other outlets have only occasionally delved into the economic-justice angle. Two years ago, espn’s investigative program Outside the Lines and ESPN.com jointly produced a month-long series, “Mixed Messages,” which dissected examples of the NCAA’s economic one-sidedness, including the contentions of the Ed O’Bannon lawsuit. In July, espn.com returned to the subject with a five-day series on athlete compensation called “Pay to Play.” And last March, during the NCAA men’s basketball tournament, PBS’s Frontline took a whack at the question of paying players. In one poignantly ticklish moment, correspondent Lowell Bergman challenged NCAA President Mark Emmert to reveal his salary on air, which Emmert huffily declined.

Tim Franklin, the former editor of both the Orlando Sentinel and The Baltimore Sun who recently stepped down as head of the National Sports Journalism Center at Indiana University, talks of the need to broaden the sports beat, to bring other perspectives to the coverage. “It is critical for news organizations to have higher education reporters and metro desks looking at this,” Franklin says. “Reporters on financial desks should be reporting on the financial statements of athletic departments. There are thousands of stories in the data in those reports that aren’t being done.”

To the extent this more elemental coverage is being done, it is largely drowned out by the endless stream of titillating details pouring from the Scandal Beat. After thirty years of a Groundhog-Day-like chronicling of transgressions and punishments, a once sober journalistic enterprise has in many ways become a source of entertainment, parceling the failings of intercollegiate athletics into the simple, binary terms sports fans can appreciate: winners and losers, sinners and saints. And as Dohrmann says, “Fans actually give a shit about who is and isn’t breaking the rules.”

Just as the pioneers who built the Scandal Beat in the 1980s sought to bring the values of public-service journalism to the sports department, the beat’s current practitioners face the challenge of how to respond to the difficult truths that their work has helped to lay bare. Because what has become clear is that the most important story in college sports is no longer a sports story at all.

Daniel Libit is the national political reporter for The Daily.