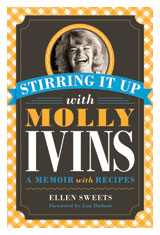

Stirring It Up with Molly Ivins: A Memoir with Recipes | By Ellen Sweets | University of Texas Press | 288 pages, $29.95

Molly Ivins was many things; columnist, civil libertarian, “professional Texan.” But she also had a reputation as a fabulous cook and legendary hostess. It’s this side of the writer that friend and fellow foodie Ellen Sweets attempts to capture in her new book, Stirring It Up With Molly Ivins.

The book charts Ivins and Sweets’s friendship, which lasted from their initial meeting at an ACLU function in 1989 to Ivins’s death from cancer in 2007, describing many memorable meals along the way. In fact, Stirring It Up, which includes thirty-five recipes scattered throughout, could best be described as a portrait through food. It’s an interesting concept for a book—but also a limiting one.

The book charts Ivins and Sweets’s friendship, which lasted from their initial meeting at an ACLU function in 1989 to Ivins’s death from cancer in 2007, describing many memorable meals along the way. In fact, Stirring It Up, which includes thirty-five recipes scattered throughout, could best be described as a portrait through food. It’s an interesting concept for a book—but also a limiting one.

In his introduction, Lou Dubose, who co-authored three books with Ivins, expresses his original misgivings about the concept of Stirring It Up. That it was neither cookbook nor memoir troubled him, but, he writes, he grew more fond of the idea because it presented a side of Ivins that was not usually public. Sweets herself addresses the issue in the book’s opening chapters:

For some, a Molly-and-food book almost feels too small for her until you consider the kick-ass job she could do on a quiche Lorraine, creamy chilled cucumber soup, a robust coq au vin, or ratatouille.

That may be so, but unfortunately Sweets assumes too much of her readers. I wanted to read more about Ivins’s life and work, to contextualize the public person whose more private side is exposed in the book’s pages. We get tidbits here and there, but with an odd, seemingly unchronological structure, it’s incumbent on the reader to piece the scraps together into a more complete picture.

In the first half of the book, Ivins comes across as a vague outline of a character among the descriptions of dinner parties and chili cook-offs. She liked hamburgers as much as she liked swanky French cuisine, she was a kind friend who often paid for meals, and without children of her own she took the nieces, nephews, and children of friends under her wing. These facts help to outline her private character, but it’s only as the book moves closer to its final chapters the outline takes a more definite shape.

Sweets’s description of Ivins’s final years, fighting a spreading breast cancer and determined to continue to live her life her own way, is more illustrative. Through interviews with friends who were there, Sweets describes a final Grand Canyon rafting trip that Ivins took despite the misgivings of friends and guides. It’s here we see the courage and strength of a woman who was determined to make the most of the time she had left.

Sweets is an engaging writer, and the book bursts with personality and humor. Stand-out moments included her description of a time she and Ivins dropped the ingredients for gumbo on the floor and decided to cook and serve it to guests anyway. Another is the story of a memorable costume party where one guest dressed as a giant tampon. It’s clear at points, though, that Sweets is very much still mourning the loss of a dear friend.

Ivins and Sweets’ friendship was formed through journalism and cemented over a hot stove. Most of the stories in the book revolve around weekends where Sweets would travel to Austin to stay with Ivins, and the pair would tackle various dishes and entertain friends. Although Ivins had many friends (Salman Rushdie and Paul Krugman are name-dropped), none were as dear as her “Austin crew,” including Sweets, with whom she ate, drank, laughed, and was able to share her real personality. Politics, the ACLU, and journalism may have been shared interests, but it was over food that these interests were shared.

“I liked that I could make Molly laugh,” Sweets writes. “Through alternating waves of internal smiles gleaned from silly and somber moments and bone-deep sadness, I kept returning to food memories and decided they are a good way to remember people you care about.”

As the book progresses, it becomes clear that cooking means much more to Ivins and Sweets than just filling bellies. For Ivins, whom Sweets portrays as perhaps more than a little out of touch with her emotions, cooking for friends and family seems to have been a way of showing love. But it was also a method of working through writers block for her syndicated columns. Sweets recalls one Sunday breakfast:

Slicing tomatoes, grating cheese, sniping and chopping chives, toasting brioche, and scrambling eggs helped clear the cobwebs and free the mind to receive an idea. When Molly worked in the kitchen she occasionally talked to herself. Not as if she was having a complete conversation, though. More like she was rearranging thoughts in her head.

For Sweets, also, the reader gets the sense that there is a strong connection between food, cooking, family, friends and happy memories. She describes her own family and the bonds formed over food, including one summer she was unemployed and spent time with her daughter (who eventually became a chef) baking bread and shopping at farmers markets.

The recipes are a nice touch and include a vast range of cuisines, from duck a la’orange to gumbo to Hungarian paprika mushrooms. Vegetarians and anyone adverse to bacon grease should steer clear, however; simply reading about the bacon-spaghetti casserole may be enough to induce a mild heart attack.

As a portrait of a friendship, Stirring It Up is a poignant work that travels beyond the public view of a writer’s life. But for a more contextualized, rounded picture of Ivins, one might be best advised to begin with more general biography, or perhaps one of her many collected volumes of columns.

Click here for a complete Page Views archive.

Nicola Kean is a journalist from New Zealand, and recent graduate of the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism’s digital program.