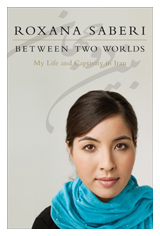

Roxana Saberi was an American freelance reporter living and working in Tehran when she was arrested by Iranian authorities in January 2009. She had been in the country for six years, and was about to return to the United States, where she planned to work on a book about Iran. Instead, she was sentenced to eight years on charges of espionage. Saberi spent 100 days in Tehran’s notorious Evin prison, eighteen of those in solitary confinement, before her sentence, which had attracted worldwide media attention, was overturned.* In Between Two Worlds: My Life and Captivity in Iran, she documents her arrest, imprisonment, and the fine points of Iranian interrogation techniques. She recently discussed these matters with Nazanin Rafsanjani, a producer at National Public Radio’s On the Media, who began the conversation by asking Saberi about the day she was arrested.

Your book begins with your arrest. What do you remember most vividly about that day?

Your book begins with your arrest. What do you remember most vividly about that day?

The intelligence agent handed me a slip of paper through the door, and I thought he was the mailman, because he told me he had a letter. I read the slip of paper and all I could really make out were the words Evin Prison. (It was written in Farsi, of course.) So I asked him, “Can I just have moment to read this?”, and I tried to shut the door on him. But I couldn’t, because his foot was propping it open, and he had this indecipherable smile on his face that I can never forget. He pushed the door open. He came in and three other men followed him, and I could tell they were all intelligence agents.

And you’re just standing there in your pajamas?

Right. I’d just thrown on a roopoosh, which is this long jacket you’re supposed to wear in front of men who are not closely related to you, and a headscarf. My hair was still hanging out the back, because I’d just woken up. They kept saying if you cooperate, you’ll be fine. We’re going to take you somewhere else to question you. If you cooperate, we’ll bring you back this evening. If not, you’ll go to Evin Prison.

First they interrogated me for several hours in an unmarked building somewhere else in Tehran. They asked me ridiculous things. They wanted me to confess, they said, that the book I was writing about Iran was a cover for espionage for the United States. They kept saying, why are you interviewing so many people? Who told you to interview these people? Who’s paying you to interview these people? I told them I was writing this book for myself. I wasn’t getting money from anybody, it was out of my own pocket.

At the end of this interrogation, we drove up north and we passed the turnoff for my apartment and went straight to Evin Prison. Evin is a terrifying word for all Iranians. Political prisoners are held there. There was a mass execution in 1988. And Zahra Kazemi, the Iranian-Canadian journalist who was detained there in 2003, died mysteriously after a few days, and no one was ever held accountable for her death.

You write about some of the terrifying things that happened during your imprisonment—and also some of the ridiculous things. For example, your interrogators pointed to your connection to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer as evidence of espionage.

Actually, it was a friend of mine who worked for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. He was a photographer there, and he had e-mailed me recently, talking about the newspaper. My interrogators said, “Do you know your friend works for the CIA?” I said I didn’t understand, he was just a journalist. And they said the paper was an arm of the CIA, because it had the word intelligence in its name.

How did you react to that?

You can’t reason with people who speak like that. I was in the hands of paranoid, crazy, close-minded people. It makes you very scared, because you know your life is in their hands, and they control you, and no matter what you say, they’re going to answer: “You’re lying! You’re lying!”

They kept bringing up your work for Fox News. Did they cite other news organizations?

No. And the Fox News reports they brought up were from way back in 2003. They claimed that these reports helped the CIA because they said Fox News is an arm of the Pentagon, and my reports had provided analysis of what was going on in Iran. But most of their questions were dealing with the book I was writing, and not so much about my reporting.

They were trying to get you to confess, but they were also trying to get names of specific people for whom you were working. And meanwhile, they said you would have to spy for the Iranian government as a condition of your release. Eventually you gave them a false confession, right?

I knew that, in the past, people had been forced to make false confessions. They’d been released, and then they’d recanted their confessions. I thought: I’m in the worst prison in Iran, in solitary confinement. I’m cut off from the world. These people can do whatever they want with me, and nobody will ever find out. And [my captors] were threatening me. They said that espionage can result in the death penalty. They also said, “We have agents all over the world, we can find your family.” When you’re in that situation, every threat is very real.

They gave me a bunch of names: Americans I knew in different capacities, journalists, friends, acquaintances, people I’d interviewed in the past. They said, “One of these people you have to name as the one who told you to use your book to spy for America.” So I picked an innocent person, a completely innocent person [who] would not be coming to Iran any time soon. I thought, I’ll get out and I’ll tell this person what I’ve done, and hopefully he’ll understand that I had to do this.

And then you had to produce a composite image of this man, who you called Mr. D.

Yeah. They took me to an interrogation room, and there was a guy sitting there with a laptop computer, [which displayed] different noses, eyebrows, eyes, lips, chin, hair. They said, “We want you to make a composite drawing of Mr. D.” So I picked out some eyes and a nose. It didn’t actually look like the Mr. D I knew, which I was very thankful for, but I had to play along.

You were just randomly picking noses and eyebrows?

Right. They had very bushy eyebrows—Middle Eastern eyebrows. [laughs]

But you recanted your confession while you were still in prison.

It was a very difficult decision to make. I knew that if I recanted while I was still there, I would make my captors furious, and they would not release me as promised. I later found out that I’d recanted two days after the Iranian authorities announced that they were going to free me within days. But I had been so ashamed of what I’d done by making that false confession. Even when I get out of here, I thought, I’m not going to forgive myself.

And that gave you a measure of newfound courage.

Yeah. I felt much more defiant, because I had proved to myself that I could be strong even in the most difficult moments.

There’s always this calculus when journalists get captured or imprisoned—news organizations aren’t sure whether to publicize what’s going on or keep it a secret. Do you think the media attention helped in your case?

I believe that it had a big impact on pressuring the Iranian authorities to release me. I knew that it was aggravating my captors, because they would say, “Tell your parents to stop talking to the media.” Look, there are [Iranian leaders] who more or less do care about the image of the regime. And we’ve seen several cases in which the media attention has caused a prisoner to be treated better or freed sooner. Maziar Bahari, for example, is an Iranian-Canadian Newsweek journalist who was detained in Iran after last year’s disputed presidential election. He was able to get out after 118 days, I believe.

Did you ever hear the NPR story that I did about you?

Which one is it? [laughs]

It was while you were in prison. At the time, I was thinking of going to Iran to cover the elections with my colleague Brooke Gladstone. But I heard an interview your dad gave to NPR, and it had a chilling effect. If that was one reason for your arrest—to discourage foreign journalists from coming—it worked.

I did hear that report, actually, after I was released. I’m sorry if I prevented you from going to Iran. [laughs] That is one of the goals they had: to intimidate other journalists, other dual nationals, other people who could work independently.

There is a specific sensitivity, I think, to dual nationals with Iranian citizenship.

There is more of a sensitivity toward us because we can speak the language. We don’t need a translator, who’s probably going to be pressured to inform on us. We don’t need a government minder to travel with us. We don’t have to stick to two or three big cities in Iran. We can go to the rural areas with our Iranian passports. We can come and go from the country. We’re independent.

While I was reading your book, I was struck by the level of detail. Do you feel like you were still functioning as a journalist while you were in prison?

When you’re in prison, you don’t have a whole lot to distract yourself with, especially in solitary confinement. A minute feels like an hour, an hour feels like a day, and a day feels like an eternity, because you spend a lot of time reviewing conversations in your head. When I was sitting in solitary confinement, I didn’t think, “I’ve got to remember this so I can write a book about it someday.” But when I came out, I did intend to write about all of this, and I took notes for several days. I just let them all pour out of my head before I forgot anything. Of course, memory has its shortcomings and mine is not perfect. I did have to reconstruct conversations—obviously they’re not all verbatim. But I did my best.

Your interrogators warned you all along not to talk about any of what happened to you. Are you nervous about going public with this stuff?

I know there’s a risk. They warned me that if I talked about these “arrangements” (that’s what they called them), they could find me anywhere in the world, and make it look like I’d died in a car accident. But I think I have a responsibility to share some of these stories. Not only my own, but also the stories of my cellmates. I need to say that what happened to me is happening to so many other innocent people in prison today. So I think it’s worth that risk. At the same time, maybe I’m not a priority at all for the Iranian authorities. They’ve got a lot of other things to focus on right now.

Why, in the end, do you think you were arrested?

While I was incarcerated, I came to various possible conclusions. I do believe they wanted to get a false confession out of me in order to intimidate Iranians trying to reach out to the West. This would provide some fuel for their argument that the U.S. has agents all over Iran in the guise of ordinary people: journalists, activists, humanitarian workers or simply people who have ties with the West. Therefore the government must be vigilant, and must crack down on these people in the name of national security. But in the long run, every time you throw somebody in prison, you’re breeding resentment across a growing part of Iranian society, and I saw that. My cellmates, their families, other prisoner’s families—sometimes they would talk while they were waiting for meetings, and they’re all angry.

Do you think you’re going to keep reporting?

Possibly. I’m not sure yet what I’m going to do in the long run.

What about going back to Iran?

I don’t think my parents are quite ready for that. And I know that now is not a good time for me to go back.

Click here to listen to Nazanin Rafsanjani’s complete interview with Roxana Saberi. For a complete Page Views archive, click here.

Correction: This story originally reported that Saberi spent four months in solitary confinement. Actually, she spent 100 total days in prison, and eighteen of those in solitary confinement. The original sentence has been updated. CJR regrets the error. Click here to return to the corrected sentence.

Nazanin Rafsanjani is a producer for NPR’s On the Media.