It was president Theodore Roosevelt who, in 1906, famously used the term “muckrakers” to disparage investigative journalists. Referencing John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, Roosevelt described a muckraker as a “man who in this life consistently refuses to see aught that is lofty, and fixes his eyes with solemn intentness only on that which is vile and debasing.”

History softened the epithet as reporters proudly adopted it. And the term retains its association with what Doris Kearns Goodwin calls a “golden age of journalism”–when profits, prestige, and progressive principles, not to mention generous pay and perks, created a singularly influential class of investigative reporters.

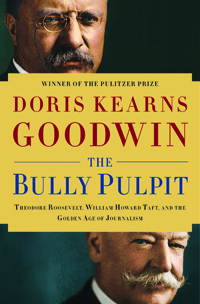

One of the achievements of Goodwin’s new history, The Bully Pulpit, is to show just how ironic it was that TR should lambast reporters for digging into the era’s muck. Among her central arguments is that Roosevelt’s accomplishments were due in large part to the transformation in public temper and perceptions fostered by the best of the new investigative journalists. These journalists, in turn, owed some of their success to personal access to a sitting president and an interchange so mutually synergistic that it would surely raise eyebrows today.

The Bully Pulpit interweaves three principal narrative strands: a biographical sketch of Roosevelt, a parallel account of his great friend and later rival William Howard Taft, and an overview of the work of those writers and editors who made McClure’s Magazine the preeminent periodical of its time.

Goodwin is the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln and No Ordinary Time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II, as well as books on Lyndon B. Johnson and the Kennedys. She is an assiduous researcher and a lucid writer who dares to tackle seemingly well-worn, subjects–like the big game of presidential history.

As with Lincoln and FDR, there is no shortage of Theodore Roosevelt biographies. Goodwin’s signature talent is to reconfigure the contours of the genre by exploring historically significant relationships, like those of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt and Lincoln and his secretary of state, William Seward.

In The Bully Pulpit, she trains her eye on the Taft-Roosevelt friendship. Goodwin’s strength is her deep empathy for her subjects. Its flipside is a tendency to sand away hard edges, to endow the past with a gauzily nostalgic glow. The sometimes inept Taft, scorned by history, has never seemed as heroic as he does here.

This latest book is a particularly ambitious project, ricocheting from presidential love stories to arcane legislative battles, from campaign anecdotes to journalistic squabbles. The mix can be unwieldy. At times The Bully Pulpit bogs down in detail, as in its chronicle of the impenetrable internecine battles that split Taft’s Interior Department and fueled his estrangement from Roosevelt. But for the most part, Goodwin has produced a readable testament to the Progressive Era, a unique relationship between two presidents, and a great moment in magazine journalism.

Roosevelt was a charismatic, if pugnacious, figure who exercised presidential power with ferocity and skill. One observer quoted by Goodwin lionized him as “a new kind of man,” and declared that “his high spirits, his enormous capacity for work, his tirelessness, his forthrightness, his many striking qualities, gave a lift of the spirits to millions of average men.” The Republican Roosevelt remains linked in the popular imagination to the bull moose and the Teddy bear, the Square Deal, the big stick, and the bully pulpit. He is credited for a trust-busting agenda that included landmark railroad regulation and passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act.

Taft is, in some ways, a more interesting case. If he is remembered at all, it is as a portly, conservative Republican who lost both his friendship with Roosevelt and the three-way 1912 election before retreating into historical obscurity. (In fact, the post-presidential Taft attained his life’s dream, ably filling the post of Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.)

Like many of Taft’s contemporaries, Goodwin seems to have been charmed by him, repeatedly lauding his kindness, good humor, and abundant gifts of both temperament and intellect. Apparently, to know the Cincinnati-born, Yale-educated Taft was to like him, or better. “One loves him at first sight,” Roosevelt said. While Roosevelt could be contemptuous of those he disliked, he noted that Taft’s “good nature, his indifference to self, his apparently infinite patience, enables him to get along with men.”

A lawyer by training and a jurist by inclination, Taft served with distinction as a state and federal judge, US Solicitor General, governor-general of the Philippines, and US Secretary of War before ascending, with Roosevelt’s indispensable support, to the presidency.

President Taft undoubtedly made some missteps, alienating conservationists and other Progressives enough to incite the ambitious Roosevelt’s 1912 intraparty bid and then (after a disputatious convention) an epochal third-party challenge. By then, the outmaneuvered Taft had moved to the right, impelled (says Goodwin) by the need to retain establishment and business support. Roosevelt veered left, taking on the Democratic nominee, Woodrow Wilson.

Goodwin is at pains to show that Taft, for much of his political life, was, like Roosevelt, a moderate reformer–committed to capitalism but aware of the perils of monopoly power and sympathetic to the plight of labor. By the time of his first presidential campaign, Taft actually had positioned himself as more progressive than TR on at least one key issue, the fight to lower protective tariffs.

In Goodwin’s estimation, where Taft fell short, compared to Roosevelt, was in his failure to engage and manipulate the press. From his days as police commissioner of New York, Roosevelt had sought to make friends of the press corps, allowing reporters such as Jacob Riis and Lincoln Steffens to help shape his agenda. As New York’s governor, he enlisted Riis to take him on a tour of tenement sweatshops, an excursion that led to improved regulation.

This pattern of mutually beneficial cooperation continued with a select group of reporters. Many were in the employ of Samuel S. McClure, the brilliant and (according to Goodwin’s description) probably bipolar founder of McClure’s. In its heyday, McClure’s gave its stars–including Steffens, Ida Tarbell, and Ray Stannard Baker–months to dig through documents, conduct interviews, and polish lengthy drafts.

Steffens’ series on municipal corruption, collected in The Shame of the Cities, and Tarbell’s exposé of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company, are among McClure’s legacies. The publisher even funded novels, notably Frank Norris’ The Octopus, based on a revolt against the predatory practices of a California railroad.

Goodwin’s analysis of Progressive Era media raises fascinating questions, the implications of which she never fully explores. This particular golden age turns out to have been rife with apparent conflicts of interest. It was not simply that the work of McClure’s writers, and of their counterparts at magazines such as Collier’s and The Saturday Evening Post, was inspired by a political agenda. This investigative tradition continues in publications such as Mother Jones and The Nation, and is embodied by advocacy journalists such as Glenn Greenwald.

Greenwald has risen to prominence by propounding a view of the federal government as an Orwellian invader of privacy. By contrast, the investigative reporters of The Bully Pulpit saw federal power as a brake on corporate and municipal corruption. Some worked intimately with the president to arouse public opinion and fashion reforms. Roosevelt invited his favorite reporters to dinner, showed them drafts of his speeches, and facilitated their research. In return, he often received advance copies of their articles, to which he appended comments.

Ray Baker’s railroad investigation for McClure’s exemplifies how the process worked. After Roosevelt learned of Baker’s research, Goodwin tells us, he invited the reporter to join him for a “family lunch” and private conversation. Baker in turn “shared with the president a detailed outline of his planned series,” arguing that “railroads were public highways that must be accessible to all on fair and equal terms.” Roosevelt confided that his biggest legislative hurdle in securing such legislation was the Senate, and advised the reporter “to be fair.”

He gave Baker a government desk and stenographer, as well as easy access to documents, while embarking on his own campaign for railroad regulation. “Mindful” of a presidential request, Baker submitted a pre-publication draft of his first article in “The Railroads on Trial” series to the president. “I haven’t a criticism to suggest,” the president wrote back, adding that the story had “given me two or three thoughts for my own message.”

Roosevelt reciprocated by sending Baker a partial draft of a railroad speech for comment. Baker offered legislative advice, spurring a heated correspondence. In the end, the president adopted some of Baker’s suggestions, and the reporter’s series “heightened public demand for regulation.” A win-win, one might say, but in a manner that not even the most ideological journalist would sanction today.

Given all this cooperation, how is it that Roosevelt came to dismiss investigative journalists as “muckrakers?” According to Goodwin, the epithet was Roosevelt’s response to an attack on the Senate in a magazine published by his enemy, William Randolph Hearst. Contrary to popular belief, she writes, the attack played little role in the subsequent breakup of McClure’s and the consequent muting of American investigative journalism. Those events she attributes in large part to the erratic McClure, with his wild business schemes and extramarital dalliances.

Frustrated, McClure’s best employees left and formed The American Magazine, which soon floundered. An age of journalistic hegemony was passing.

What are the most potent lessons of The Bully Pulpit? Not just that editors should treat their reporters with tender loving care, though that is a seductive prescription for journalistic success. Goodwin says that she hopes her tale somehow rouses readers to “demand the actions necessary to bring our country closer to its ancient ideals,” a vague wish that brands her as the gentlest and most allusive of muckrakers.

Julia M. Klein is a longtime CJR contributor and a contributing book critic for The Forward. She is a cultural reporter and critic in Philadelphia. Follow her on Twitter @JuliaMKlein.