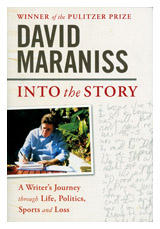

Into the Story: A Writer’s Journey Through Life, Politics, Sports and Loss | By David Maraniss | Simon & Schuster | 283 pages, $26

The collected works of journalists often fall flat in book form. The recycled pieces from newspapers and magazines can seem stale. Frequently, a writing style that is perfectly serviceable for quick consumption turns out to be unremarkable between hard covers.

But once in a while, an anthology clicks. A few even become journalistic classics. Perhaps the most notable example is Jessica Mitford’s Poison Penmanship: The Gentle Art of Muckraking. That collection, originally published in 1979, boasted a witty style and a memorable, gently didactic introduction by the author. But now we can add another title to this honor roll: David Maraniss’s Inside the Story: A Writer’s Journey Through Life, Politics, Sports and Loss.

The simplest argument for its inclusion would be for me to stop writing and instead persuade my CJR editor to publish the author’s introduction verbatim. But that’s not going to happen. So instead, I will distill some key lessons from those ten pages, as well as from the thirty-two pieces that have previously appeared in newspapers, magazines, and in some of Maraniss’s previous books (which include biographies of Bill Clinton, Al Gore, Newt Gingrich, Roberto Clemente, and Vince Lombardi, as well as studies of the Vietnam War and the 1960 Rome Olympics).

The simplest argument for its inclusion would be for me to stop writing and instead persuade my CJR editor to publish the author’s introduction verbatim. But that’s not going to happen. So instead, I will distill some key lessons from those ten pages, as well as from the thirty-two pieces that have previously appeared in newspapers, magazines, and in some of Maraniss’s previous books (which include biographies of Bill Clinton, Al Gore, Newt Gingrich, Roberto Clemente, and Vince Lombardi, as well as studies of the Vietnam War and the 1960 Rome Olympics).

Maraniss is especially skilled at profiles. He makes complex individuals come alive on a printed page about as well as any journalist I have encountered. How does he do it? Into the Story offers any number of tips, starting with the author’s nuanced view of human nature.

Most individuals, he argues, “are a combination of good and bad.” Making a concerted effort to understand that mixture is always worthwhile. This means abandoning the notion adopted by so many journalists and biographers, according to which individuals can be fairly described according to a single overriding motivation, such as ambition or greed or romantic love. As a biographer myself, I have struggled with and rejected such reductionism. So does Maraniss, for reasons that involve both humility and empathy.

“Like all humans, I carry a set of biases,” he writes, “people with whom I agree or disagree, policies that I admire, and policies that I abhor. But my obsession as a biographer goes in a different direction, not toward molding subjects so they fit into my worldview, but trying to comprehend theirs–the forces that shaped them, why they think and act the way they do.”

To show these principles in action, Maraniss points to three pieces about Bill Clinton in the collection. (Maraniss wrote First in His Class, which I consider the first important Clinton biography.) The three stories, he notes, might lead readers to “reasonably deduce that there were times when I liked [Clinton] and times when I did not, but neither sentiment is particularly useful.” Instead, his research into the president’s life led to the conclusion “that you could not separate the good Clinton from the bad one, that his impulses for better or worse arose from the same well of need and desire, and that there was a repetitive cycle of loss and recovery in his life. When he was down, he would find his way back, and when he was on top, he would find a way to screw up again.”

That brings us to the next lesson. In the author’s view, journalists are obliged to seek the truth, no matter how elusive. When a reporter hears contradictory statements from two respected sources, he or she should not simply assign them equal weight. Indeed, for Maraniss, such a reportorial standoff means “that I probably have more work to do, more people to talk to, more documents to search for, more thinking about the context of their accounts and what makes the most sense. It is not quite a science, but it is a serious endeavor with the same respect for evidence and rational thought.”

Maraniss makes the additional point that if a journalist expects truth from a source, it is vital to demonstrate “patience, directness and honesty” when dealing with that source. He uses the example of Clark Welch, whose testimony was essential to what became They Marched Into Sunlight: War and Peace, Vietnam and America, October 1967. Welch did not want to cooperate unless the author promised to portray his company of soldiers positively in print. Maraniss could not make that promise while his reporting was still under way. Yet he finally managed to win Welch’s cooperation without compromising the integrity of his work—a process he explains in detail.

On that occasion, Maraniss began his reporting without Welch’s cooperation. “I’ll let you know what I’m finding along the way,” he told his reluctant source. “But I can’t promise you that I’ll be good to your boys because I don’t know what I’ll find.” The author kept his part of the bargain—and in doing so, he won Welch’s trust. “He eventually shared virtually everything with me,” Maraniss recalls, “including his deepest feelings as well as his letters.”

A third lesson concerns the limited nature of human memory, around which reporters must constantly work. These limitations are especially acute when sources “try to recount the precise chronology of events, something particularly important to writers of nonfiction narrative,” Maraniss says.

Over and over, he ran afoul of such limitations when he tried to describe warfare in Vietnam. As he admits, he “could not rely on interviews with the survivors about the timing of what happened as they marched into the jungle.” To some of the veterans, seconds had seemed like hours and hours like seconds. The pressure of battle had distorted their perceptions–and the distortions often increased, not decreased, through the years. As a result, the author stresses the importance of locating contemporaneous written accounts. An eyewitness, even with the best of intentions, can prove to be astoundingly myopic.

Maraniss says that “the world of nonfiction writing is a continual graduate school.” On the basis of the many lessons to be found in this stellar collection, I would happily nominate him as professor of the year.

Click here for a complete Page Views archive.

Steve Weinberg is the author of eight nonfiction books. His most recent book, Taking on the Trust: How Ida Tarbell Brought Down John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil, has just been published in a paperback edition.