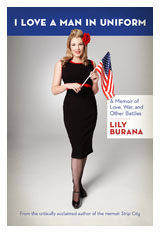

I Love a Man in Uniform: A Memoir of Love, War, and Other Battles By Lily Burana | Weinstein Books | 368 pages, $23.95

In the six years since the invasion of Iraq, the memoir industry has gone through almost as many dramatic highs and lows as the war itself. The first-person boom and bust has brought plenty of narratives from drug addicts and repentant criminals, but relatively few from those on the battlefield. In I Love A Man in a Uniform, Lily Burana marches into that lightly populated genre with an outsider-on-the-inside perspective: she may not be a soldier, but she’s a soldier’s wife. And while war and the people who fight it are the book’s ostensible focus, Burana’s memoir is also a dramatic demonstration of what happens when ideological opposites attract.

Upon meeting her titular “man in uniform,” the author dismisses him as “a bloodthirsty hawk with politics so radically rigid, he’d make Strom Thurmond look like a dope-smokin’ hippie.” But as she quickly learns, he is not just another hot-headed slab of muscle with a hunger for combat. Mike (who is identified by his first name only) is the possessor of a dry wit, a subscription to Harper’s, and a master’s degree in history.

Upon meeting her titular “man in uniform,” the author dismisses him as “a bloodthirsty hawk with politics so radically rigid, he’d make Strom Thurmond look like a dope-smokin’ hippie.” But as she quickly learns, he is not just another hot-headed slab of muscle with a hunger for combat. Mike (who is identified by his first name only) is the possessor of a dry wit, a subscription to Harper’s, and a master’s degree in history.

Burana, of course, also defies easy stereotype. This former stripper spent years taking off her clothes for strange men in strange cities; she has an array of tattoos and an arrest record to her name. Yet she made a literary reputation for herself, publishing pieces in major newspapers as well as a novel, Try, and an earlier memoir, Strip City: A Stripper’s Farewell Journey Across America.

Not surprisingly, this odd couple intended to take it slow. Then came 9/11. In the ensuing months, while the Bush administration made the case for preemptive war, Mike made his own for preemptive marriage. If there was a war, the argument went, he could be deployed, and if he was deployed, the unthinkable could happen. Off to City Hall they went. As it happened, Mike’s initial tour of duty in Iraq was brief. And soon after his return, he was recruited for a plum faculty position at West Point. With the job came subsidized housing, top-notch healthcare—and a host of protocols, social mores, and obligations that soon overwhelmed the recovering anti-establishmentarian author. The unspoken rules at West Point governed even interior decorating.

“Artwise,” Burana writes, “there was a delectable penchant for quilts, primitive country prints of cottages, hearts, and ducks, and military scenes. Nothing provocative—Stivers’ Christmas Raid, yes. Picasso’s Guernica, no. The comforting domesticity provides a perfect retreat from the battlefield’s severity. If you are war-weary and homesick, maybe you don’t want to park your butt in an Eames chair and gaze upon the chaos of a de Kooning or the arctic-cool irony of a Rauschenberg.”

Because her past is so far removed from this buzz-cut milieu, Burana’s observations of military minutiae are keen. She picks out details that only an outsider would notice. Ice, for example, is one of the most valuable commodities for a soldier serving in Iraq: each camp gets 35,000 pounds per day—about four pounds per soldier—but in the scorching heat, drinking water more closely resembles something ladled out of a hot tub. Other inside tips are more bureaucratic. In the scale of infractions outlined by the Uniform Code of Military Justice, “sodomy” ranks somewhere between “maiming” and “arson.” Also: a soldier’s “chart” can accommodate up to seven wives. The first wife is coded as a “30,” and since Mike is divorced from his first wife, Burana is known in official terms as his “31.”

From time to time, the author is derailed by incongruous and distracting pop-culture references. Even her title is a nod to the Gang of Four’s “I Love a Man in a Uniform,” which had its radio heyday in the early 1980s. Still, most of Burana’s references are painfully of-the-moment: West Point wives are “Mean Girls with lawn ornaments,” a hipster in the commissary is a “Vice magazine answer to the Mod Squad.” At least one of the above is going to alienate a reader who isn’t as hip as the author.

Yet the drama of Burana’s unlikely relationship with her husband keeps the pages turning. While the oft-quoted statistic is that fifty percent of marriages are doomed to fail, a military marriage is an order of magnitude more likely to end in divorce. In the book’s second act, Burana and her husband are both diagnosed with PTSD, and their marriage begins to unravel. She leaves the bucolic, cozy domesticity of West Point housing—which she calls “military Mayberry”—to lick her identity-crisis wounds at a nearby crappy motel.

Burana’s greatest strength is her ability to fully inhabit each moment: when she recounts her early, rapturous days with Mike, the telling is in no way colored by the subsequent breakdown. Nor is her account of the breakdown tainted by the recovery that followed. Here is the mark of a formidable memoirist.

Equally remarkable, and somewhat disconcerting, is how little the author comments on the war itself. To be sure, Iraq is conspicuous by its absence—the bloody conflict that dare not speak its name. Burana distracts the reader with her suspenseful and involved storytelling, waiting until the end of the book to address her dignified silence on the matter. By then, it feels a little too late.

Ultimately, though, we side with Burana, no matter how drunk on United States Armed Forces Kool-Aid she may be. Even those of us who don’t support the war can support the troops. Similarly, we can support a woman whose most important relationship is not with the war or the politics surrounding it, but with someone paid to deal with both. And though we might not be fully behind every word of this story, I Love A Man in Uniform is an honest, illuminating look at what we can only call the military-industrial multiple-personality complex.

Courtney Reimer is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Village Voice, and New York magazine.