In this season of a perfectly dull mayoral election, and in this year that is the fortieth anniversary not only of Woodstock, Chappaquiddick, the moon landing, the Manson murders, and the Miracle Mets but also the celebrated Mailer-Breslin campaign of 1969, let us pause for a couple hours to dust off and read Managing Mailer. In this half-great campaign memoir, Joe Flaherty chronicles that bravura effort on the part of two once-and-future Pulitzer Prize winners to gain custody of City Hall. If nothing else, it reminds us that there was once a time when guys like Norman Mailer and Jimmy Breslin–novelists, for goodness sake!–had sufficient self-regard to think that if they offered themselves to the voters, the voters just might accept.

In this season of a perfectly dull mayoral election, and in this year that is the fortieth anniversary not only of Woodstock, Chappaquiddick, the moon landing, the Manson murders, and the Miracle Mets but also the celebrated Mailer-Breslin campaign of 1969, let us pause for a couple hours to dust off and read Managing Mailer. In this half-great campaign memoir, Joe Flaherty chronicles that bravura effort on the part of two once-and-future Pulitzer Prize winners to gain custody of City Hall. If nothing else, it reminds us that there was once a time when guys like Norman Mailer and Jimmy Breslin–novelists, for goodness sake!–had sufficient self-regard to think that if they offered themselves to the voters, the voters just might accept.

In retrospect, it’s clear that you couldn’t call it a significant campaign. It wasn’t like William F. Buckley Jr.’s run for mayor in 1965, in which one can detect the seedlings of the conservative movement to come. No, the Mailer-Breslin circus was very much of its moment, concerned with the dominant issues of the day: race and poverty, Vietnam, problems with education and state aid. Nobody was saying he had a funny feeling that a massive fiscal crisis was only a few years away. The big idea behind the campaign–liberating New York City from the clutches of Albany and turning it into the fifty-first American state–had been floated by Henry George nearly a century before.

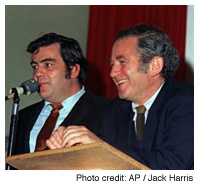

No, what was special about the campaign was the candidates’ bravado (“Throw the rascals in!” was one campaign slogan), their audacity (“No More Bullshit” was another), and above all, their facility with words–soaring words, funny words, trenchant words, critical words, witty words. “I can look without horror upon any man whose hand I have to shake,” Mailer said at one appearance. “The difference between me and the other candidates is that I’m no good, and I can prove it.”

Luckily, there was a man of words on hand to capture it all. Flaherty, who was then thirty-three and a Village Voice columnist, was among the many writers drawn to the candidates. One after another, the great bylines of the era traipse through these pages: Peter Maas, Jack Newfield, Peter Manso, Ellen Willis, Geoffrey Stokes, Gloria Steinem. Still, there never seems to have been a doubt that Flaherty, a lesser luminary, would get the job of organizing the tilt at this particular windmill. Perhaps it was his earlier stint as a longshoreman that made him relatively immune to the terrors of scut work. In any case, Flaherty ran the show, which ultimately came nowhere close to making Mailer the mayor or Breslin the city council president.

To be honest, it’s not clear that Flaherty was any great shakes as a political operative. What is clear from page one, however, is that he was a sharp observer and a mighty mean man with a metaphor. Flaherty noted that the actor Buzz Farber possessed “one of those muscular Robert Jordan handshakes that seems to signify the blowing of a bridge rather than a greeting.” The rival candidate Herman Badillo had “none of his Latin brothers’ fire and life, and in his dark Petrocelli suits, he looked wooden–a Puerto Rican Robert Goulet.” Gloria Steinem’s apartment was “wallpapered in a black and white zebra pattern similar to the motif of that bastion of decadent capitalism, the El Morocco, interrupted by posters of Che Guevara and Cesar Chavez.”

Some of Flaherty’s set pieces–Mailer’s sparring match with cops at John Jay College, for example, or Breslin’s hilarious humiliation at the hands of young feminists at Sarah Lawrence–are brilliant feats of narrative. Yet the author is also smart enough to get out of the way and let Mailer and Breslin, his effective coauthors, take over the story when necessary. Here the dynamic duo storms the citadel at Queens College:

About a thousand students sat in a sun-baked mall waiting for the candidates. Others sat or dangled from walls or windows, giving the campus the look of a seized border town. And then there was the heat and the flesh–young men, shirtless, with bodies that had not yet made the acquaintance of fat, and young girls in shorts whose brown thighs were covered with a veil of blond algae…. [T]he kids were joyously shouting, “What about Nixon? What about the ABM? What about Daley?” Breslin stood waiting for them to quiet down. Finally Mailer could no longer resist the compelling of stink of sweat and sensuality. He put his arm across Breslin’s body and pushed him aside, seizing the podium. And to answer all their questions… he screamed “Fuck!”, plunging into them as though they were a pair of open legs.

If Managing Mailer is only half-great, it’s because Flaherty, who would write a very good novel called Tin Wife before succumbing to cancer in 1983, had to spend about half his time dealing with nuts and bolts instead of his leading men. Some readers might find that a good thing. Flaherty did have a serious case of hero-worship. To him, Mailer was a visionary: “He proceeded to take [the audience] on a tour of America’s spiritual wasteland, stopping along the way for commentary on our alienation, racism, technological madness, and impotence… convincing a collective body that the sadness in his soul was symbolic of the sadness in the land, that his personal tragedies weren’t encased in his psyche but wrapped in a shroud of red, white and blue.”

But as much as the author idolized the candidates, he was objective enough to call a spade–well, something spade-like. “Flaherty treats a dozen delicate egos like golf balls, and then proceeds to see how far he can whap them,” blurbed Mailer on the cover of the 1971 paperback edition, and there’s some truth to this assessment. We see Breslin’s moodiness and Mailer’s nastiness and unreliability when drinking. One comes away from the book very sorry to have missed their candidacy, but not very sorry that they lost.

One of the real pleasures of Managing Mailer is realizing what isn’t there. This was a campaign composed of gifted amateurs who were full of ideas, many of them half-baked, about how to win. David Garth and Pat Caddell and Roger Ailes were just inaugurating the era of pollsters, consultants, and media masters; this was one of the last homemade efforts. It’s quaint and somewhat amusing to read that having gathering 15,000 precious signatures needed to qualify Mailer for the ballot, Flaherty locked the vital papers in Art D’Lugoff’s safe at The Village Gate. Also absent is the omnipresent cadre of bankers and brokers who dominate our town today. Mailer spoke in peoples’ apartments, collecting five-dollar checks from skeptic liberals who today live in Larchmont and Great Neck and probably still dine out on their story of meeting Mailer.

Present, instead, is a literary New York that is gone. This is a candidacy of writers (indeed, Steinem rebuffed the momentary notion that she run for comptroller because she didn’t want the thing to look like “a campy literary exercise.”) The candidates charted their ups and down by what Murray Kempton or James Wechsler wrote in the Post and what Sidney Zion or Russell Baker said in the Times. They even took note of a rather carnal evaluation of the candidates that appeared in Screw. At one rally, Mailer even argued that the reason “everybody is going crazy in this city [is] because they have no objective correlative.” Barack Obama may be a literary politician, but you can bet he never made a point like that.

In the end, Mailer and Breslin could never surmount the cloud of dilettantism that dogged their effort. On election day, both candidates lost, each finishing ahead of one rival–and on they went, to many other adventures and triumphs. No doubt there were many other excellent writers in their era, maybe even some better ones. But they were the stars, and it’s fair to say that their quixotic campaign, so vividly conveyed in Flaherty’s memoir, is what first made them larger than life.

Click here for a complete Page Views archive.

Jamie Malanowski has been an editor at Spy, Time and Playboy. He is the author of the novel The Coup.