In recent years, as the American public has grown exhausted by news of war, it has become ever more fascinated by war photographers. When the photojournalists Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros were killed in a mortar attack by Qaddafi forces two years ago this April, for instance, it was one of the biggest news events of the Libyan civil war. This was, of course, partly because many in the media knew Hetherington and Hondros, but it also had something to do with how they fit the profession’s romantic image. Take it from David Carr: “Hetherington was a war photographer in every regard. Tall, brutally handsome and modest, he had a British accent plucked from a Graham Greene novel and the body fat of a Diet Coke.”

As Emily Nussbaum noted in her recent New Yorker review of HBO’s documentary series Witness, which focuses on conflict photographers like France’s Véronique de Viguerie, “It’s no surprise that viewers may find it easier to watch a profile of a brave and beautiful French photojournalist than a gruesome documentary about child soldiers in Africa.” Unfiltered images of violence are as distressing as theatrical violence is popular. The media are always coming up with new ways to dilute the horrors of war for the casual news consumer.

Understanding this inevitable dilution puts the job of a war photographer in an interesting light. Their images must get as close as possible to the reality of extreme, horrifying situations, and somehow manage to compel the viewer to move deeper into them rather than turn away. Photographs can inure us to violence, but they can also serve as moral touchstones, reminders not only of an event itself but of the need to feel something about that event. The best pictures close the gap between distant images and our own emotional reality.

No photographer thought more deeply about that dividing line than Tim Hetherington. As Hetherington’s friend and collaborator Sebastian Junger told me recently, “Tim was particularly interested in how the media shapes the society that then uses the media. That sort of circle.” In fact, Hetherington had gone to Libya to document a similar phenomenon: the idea that Libyan rebels, plunged suddenly into war without prior experience, were looking to media and popular culture to discover how a rebel soldier should look and act.

During an initial brief trip to Libya in March 2011, he had been disturbed by the posed nature of the conflict: journalists taking heroic photos of rebels who were in fact merely untested civilians mugging for the camera with guns. His new project was an attempt to confront, and transcend, this dynamic. “We have to fight making propaganda,” he told a friend, the New York Times photographer Michael Kamber, just before heading back to the front line. “The media have become such a part of the war machine now that we all have to be conscious of it more than ever before.”

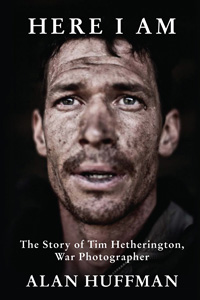

Hetherington died only a few months after Restrepo, the documentary about American soldiers in Afghanistan he co-directed with Junger, was nominated for an Academy Award. While he will probably remain best known for Restrepo, many who knew Hetherington are working to preserve his larger sensibility and mission—topics that hint at the work he might have gone on to do. Last fall, Kamber assembled an exhibition of Hetherington’s final photographs at the Bronx Documentary Center. A biographical documentary, Which Way is the Front Line from Here?, directed by Junger, will premiere at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2013. And a print biography, Here I Am: The Story of Tim Hetherington, War Photographer, by Alan Huffman, will be published by Grove this March.

Huffman recounts Hetherington’s career in chapters that expand on the many conflicts the photographer covered: the Liberian civil war; the genocide in Sudan and its spillover into Chad; the American occupation of Afghanistan. His point, though not stated explicitly, seems to be that you can’t understand Hetherington without understanding the violence he was drawn to document. Huffman succeeds in immersing us in Hetherington’s daily reality while in conflict zones, and many excellent interviews with friends and colleagues add a personal dimension to the photographer’s extraordinary life. But the best biographies also explore the minds of their subjects, a task at which Huffman is less effective. Though Hetherington was intensely interested in how images of conflict were disseminated, contextualized, and viewed by the public, his biography is not, for the most part, a book of ideas.

Hetherington’s first experience of war was as one of only two Western journalists working behind rebel lines in Liberia in 2003, photographing a conflict characterized by elaborate, theatrically absurd brutality. Huffman quotes the filmmaker James Brabazon, with whom Hetherington collaborated on the documentary An Uncivil War, as saying of Liberia, “It wasn’t just two armies facing each other off; it was two groups of young men who were absolutely enamored with theatrics of war—wearing dresses, eating each other, hacking off each other’s limbs.”

But Hetherington was able to document this violence without allowing it to distract him from the Liberian people’s humanity. His photographs—a moment of intimacy between a rebel and his wife before he heads to battle; a portrait of a contemplative man in fatigues sitting beside a grenade—challenged the notion that Liberia could be entirely defined by its atrocities. And unlike most of the press corps, Hetherington stayed in Liberia long after the war ended. The book he eventually produced, Long Story Bit by Bit: Liberia Retold, is proof that one can simultaneously document violence and beauty in a way that feels authentic and accessible rather than counterintuitive.

Huffman argues that “Hetherington saw very little distinction between being a journalist, a humanitarian, an observer, a witness, or a participant.” Though Huffman fails to parse the implications of that claim, he does work to convey its importance, noting that “Hetherington felt it wasn’t enough merely to show what had happened, that photography could convey a deeper narrative and influence the direction that narrative would afterward take.”

The most literal proof of Hetherington’s belief in the power of photography to influence events was his work for Human Rights Watch in Sudan. The images he took home—including portraits of survivors who had been shot or hacked by machete, which served as the first visual evidence that the Darfur conflict was bleeding into Chad—were in large part responsible for bringing international attention to the crisis. But this belief in the power of images also showed in the way he approached his work.

One product of Hetherington’s time in Afghanistan was an installation piece that intercut softly lit still photographs of sleeping soldiers with the sounds and images of combat, representing their dreams. The piece is incredibly subtle, particularly by the standards of war photography, but Hetherington felt it was the closest he’d ever come to “expressing what it’s like to be in a chaotic war situation.” His thoughts on the piece reveal the extent to which he considered the ultimate impact of his work, and also get at the quiet subversiveness of many of his images. “I like this idea that the project challenges what we think we know war is about,” he said. “I’m interested to reveal parts of conflict outside of the mass media dialogue.”

Nearly half of Huffman’s book is devoted to reconstructing Hetherington’s final days in Libya. Whereas in Liberia it was largely the responsibility of Western journalists to make a record of what was occurring, by the time Hetherington arrived in Libya, cameras, wielded by both civilians and soldiers, had become an inescapable part of the war effort. The Brazilian photographer André Liohn noted that the Libyans “went to war with almost as many cameras as weapons.”

This, too, was a concept Hetherington was trying to understand. He realized that the modern media environment was such that there was nothing particularly novel about images of combat, and that journalists had to do more to distinguish their work both aesthetically and intellectually. While in Libya, Hetherington had an idea for a new installation piece. He would collect hundreds of cell phones from Libyans who had used them to take pictures of the war, and then arrange them to form the image of the painting Guernica, which depicts civilian casualties of war in Picasso’s native Spain.

Writing in the Times about the exhibit he put together of Hetherington’s last photos, Michael Kamber said, “More than any journalist I know, Tim was conceptual in his work. He thought about the big ideas behind an event, the dynamics, history and driving forces. He then tailored his photography and multimedia work accordingly, trying to dig through and expose these forces. His methods stood in stark contrast to many of us who photograph what fate and others present to us, unwittingly allowing the narrative to be shaped through our acquiescence.”

Hetherington went to Libya without an assignment from a news agency, and, notably, without digital photographic equipment that would even allow him to sell his Libya photos for use in real-time coverage of the conflict. He went in pursuit of ideas he was still only beginning to develop, and as part of an ongoing attempt to better understand the nature of conflict and the methods with which it could be documented in the 21st century. He was once again attempting, as he said of his film Diary, “to link our Western reality to the seemingly distant worlds we see in the media.”

Near the end of that film, there’s a scene of Hetherington in a bed. His back is to the camera and he’s on the phone, trying to explain his work to someone. He says, “There’s a political situation or a war or a catastrophe and I make pictures to try to understand what is happening there for myself. If you think by looking at the pictures that there’s no hope, then I’m, I’m, you know. . .” He trails off and the scene ends.

When I asked Junger about this soon after Hetherington’s death, he noted that the sentence didn’t end there. Instead, Hetherington chose to cut away. “I don’t know what he said,” Junger told me. “But it’s an interesting game to imagine what he could have said in that empty space that he left.” And now that’s the task left to all of us.

Michael Canyon Meyer is a freelance journalist and former CJR staff writer. Follow him on Twitter at @mcm_nm.