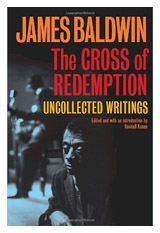

The Cross of Redemption: Uncollected Writings | By James Baldwin | Pantheon Books | 320 pages, $26.95

To introduce The Cross of Redemption, a new book of uncollected writings by James Baldwin, editor Randall Kenan evokes other modernist giants who “dared put so much demand on the language.” Kenan places his subject in the company of William Faulkner, Virginia Woolf, and Malcolm Lowry. But these other literary polymaths tended to save their pyrotechnics for their fiction. Baldwin shone in that other form, the one Gay Talese has bemoaned as “the Ellis Island of literature” (although it has surely gained some cachet since Talese’s salad days): literary nonfiction.

A preacher’s son, Baldwin grew up in Harlem as a teenage evangelist, entering the pulpit at fourteen and abandoning it three years later. In his nonfiction above all, one can see that the skill for oratory stayed with him—transferred to the page for a wider audience. His language could sometimes be baroque. Yet his message always cut straight through, even when his opinions were hard to swallow. The reader feels compelled to keep reading, no matter how raw or unapologetic the subject material.

A preacher’s son, Baldwin grew up in Harlem as a teenage evangelist, entering the pulpit at fourteen and abandoning it three years later. In his nonfiction above all, one can see that the skill for oratory stayed with him—transferred to the page for a wider audience. His language could sometimes be baroque. Yet his message always cut straight through, even when his opinions were hard to swallow. The reader feels compelled to keep reading, no matter how raw or unapologetic the subject material.

The Cross of Redemption showcases the sheer range of Baldwin’s nonfiction. The volume includes essays and speeches, profiles, book reviews, letters (private correspondence as well as open letters to Angela Davis and Archbishop Desmond Tutu), and a handful of forewords and afterwords. We see Baldwin playing different roles over the course of his career: cultural arbiter, public figure, commentator. Readers will also find one short story, “The Death of a Prophet,” tucked in at the end—although this lone fiction feels a bit like an interloper, a stray in a collection that already lacks for cohesion.

To be honest, this is not the cream of Baldwin’s work as an essayist. There have been two previous collections, The Price of the Ticket and a posthumous Library of America volume, Collected Essays. And although the “lost” work gathered here is consistently strong in argument and style, not all of it is the author’s best writing.

Still, there are numerous stand-outs. In “Black English: A Dishonest Argument,” a speech given at Detroit’s Wayne State University in 1980, Baldwin addresses the idea of “whiteness” and black identity in the Western world:

The black American has no antecedent. We, in this country, on this continent, in the most despairing terms, created an identity which had never been seen before in the history of the world. We created that music. Nobody else did, and the world lives from it, though it doesn’t pay us for it. In the storm which has got to overtake the Western world, we are the only bridge between their history which is the past and their history which is the present…. [T]he world is not white; it never was white, cannot be white. White is a metaphor for power, and that is simply a way of describing Chase Manhattan Bank. That is all it means, and the people who tried to rob us of identity have lost their own.

Passages like the one above, which can also be found in “On Being White … and Other Lies” and “The White Problem,” are as commanding in their discussion of race as Baldwin’s book-length manifesto The Fire Next Time.

Another of the collection’s strongest pieces is arguably its most entertaining. “The Fight: Patterson vs. Liston” shows how efficiently Baldwin could juggle character sketches and sports reportage. At one point Gay Talese, who was covering the same bout, makes a cameo appearance. This mini-portrait, written with obvious affection, is a nod at a master of the genre—but there is also an implicit comparison. Baldwin, the piece shows, is just as good.

Most importantly, The Cross of Redemption allows readers a glimpse of how Baldwin developed as a writer and thinker. The collection spans nearly four decades, from the 1950s through the 1980s. We see Baldwin wield the first person with precocious authority in two book reviews of Maxim Gorky’s fiction, written when he was in his early twenties. This future master of the personal essay had already pointed himself in the right direction. Even the early, unvarnished “Death of a Prophet,” about a young man coming to terms with his father’s death, seems to anticipate Notes of a Native Son.

What’s surprising is how relevant Baldwin’s thoughts on race, society, and culture remain. In 1961 he gave a speech to the Liberation Committee for Africa, in which he alluded to Bobby Kennedy’s comment that he, too, could be president one day. Pondering the idea of an African-American in the White House, Baldwin said, “It never entered this boy’s mind, I suppose—it has not entered the country’s mind yet—that perhaps I wouldn’t want to be. And in any case, what really exercises my mind is not this hypothetical day on which some Negro ‘first’ will become the first Negro President. What I am really curious about is just what kind of country he’ll be President of.” It is almost impossible to read these words without wondering what their author would have said about Barack Obama and the America that elected him.

Note, too, that in his response, Baldwin’s focus is not on the hypothetical black president, but on the greater society. The bulk of his writing involves issues of race or class in some way, but as a writer, he was never consumed by them. On the most basic level, his work can be read as a chronicle of the peculiar, often cruel ways in which people interact with each other.

But perhaps the best way to get a grip on Baldwin’s deep-focus approach is to read what he has to say about his own writing. A 1962 issue of The New York Times Book Review asked authors to talk about their own bestselling works, and to speculate about “what they believe there is about their book or the climate of the times that has made [it] so popular.” Baldwin’s answer speaks specifically about his novel Another Country, but the statement could apply to his entire oeuvre: “I would like to think that some of the people who liked my book responded to it in a way similar to the way they respond when Miles [Davis] and Ray [Charles] are blowing. These artists, in their very different ways, sing a kind of universal blues, they speak of… what it is like to be alive.”

Click here for a complete Page Views archive.

Kimberly Chou is a writer in New York.