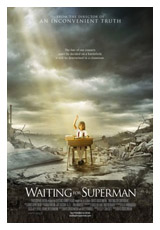

I sobbed alongside my graduate students as we watched the ending of Waiting for Superman, the heat-seeking documentary that has garnered rave reviews and generated an uncommon level of discussion about public education in America. We all wept—the young men, too—despite our awareness that the filmmakers had manipulated us with misleading and lopsided arguments.

The emotional power of Superman swayed even our famously unflappable President Obama, who hinted at some tearing up of his own when he told the Today show that the film’s ending was “heartbreaking.” What else could it be? Five impossibly adorable children from D.C., New York City, and California pin their futures on a lottery ball tumbling their way, winning or losing them a spot in a coveted charter school.

In one scene, Anthony, a fifth-grader from D.C., stares at a note card on his lap with his name and number on it. At the public lottery in the school gymnasium, every other name is called—but never his. The camera lingers on his little hands; he flicks the card, as if that might conjure a different fate. It’s unbearable to contemplate his helplessness, the injustice of his rejection, and the profound consequences for the rest of his life.

In one scene, Anthony, a fifth-grader from D.C., stares at a note card on his lap with his name and number on it. At the public lottery in the school gymnasium, every other name is called—but never his. The camera lingers on his little hands; he flicks the card, as if that might conjure a different fate. It’s unbearable to contemplate his helplessness, the injustice of his rejection, and the profound consequences for the rest of his life.

This is psychological torture no child should have to endure. And from that metaphorical moment, Oscar-winning director Davis Guggenheim squeezes every drop of outrage. As Gail Collins said in a New York Times column, “By the time you leave the theater you are so sad and angry you just want to find something to burn down.”

The question is, what exactly would the moviemakers have us burn? Where to direct all that righteous anger? Is Guggenheim pressing for a thoughtful dialogue and real transformation, or a self-destructive rush to the barricades? And why are most journalists not asking these questions?

Stripped to its essence, the film’s solutions are seductively simple. Officials should fire bad teachers, close down failing public schools, and replace them with charters—schools funded with public dollars and run by private boards. This is Guggenheim’s master narrative, set against a backdrop of broad crisis in public education. Teachers unions are the villains here; charter schools the heroes.

To make this point, the film avoids any probing examination of a failing school, nor does it provide examples of good or bad classroom teaching. Instead it makes use of selective statistics, colorful graphics, and animated cartoons, which mock the techniques (variously known as Pass the Trash, Turkey Trot, and Dance of the Lemons) used by principals to rid their classrooms of ineffective teachers. Finland, long a Monty Python punch line, is used here in a similar vein, as the nation that is putting America to shame in all areas academic. (In fact Finland’s story actually contradicts the master narrative—but more on that later.)

There is not much room on this storyboard to consider broader factors. The film ignores decades of white flight from urban schools, the growing income divide between the wealthy and the poor, test-driven reforms that strip richness from the curriculum, the systematic devaluation of teaching as a profession, and the dismantling of desegregation laws, welfare support, and health care benefits.

Other voices are left unheard and unacknowledged, including disaffected parents, community leaders, and civil-rights groups that are beginning to push back against the tide of mass firings and charter-school creation. Missing in action from any frame are the NAACP, the Urban League, and the Washington, D.C. voters who recently ousted Mayor Adrian Fenty in large part because his heavy-handed education initiatives excluded their participation.

Nor does Guggenheim present alternative solutions. New York City, for example, is home to a growing, under-the-radar consortium of urban public schools that have had decades of measurable success with underprivileged children, focusing on students’ reasoning abilities rather than test-taking prowess. A more sober, less commercial documentary produced by Frederick Wiseman in 1994, High School II, explores the ideas behind these progressive schools. The film also does something Superman does not attempt: it burrows inside an East Harlem high school and its classrooms to try and understand how and why it works.

In Superman, instead, troops are rallied for a partisan battle. On one side are the self-described rebels, the good reformers, storming the gates of the status quo; on the other side, anyone who disagrees. A pre-film-release cover story in New York magazine allied these warriors with Obama (who was himself described as challenging “his party’s hoariest shibboleths and most potent allies.”)

The notion of creating a functional, even superior, education system is not, of course, a new one. Public school reforms have come and gone and come again in waves of innovation and regulation since the Soviets beat us into space with Sputnik in the late Fifties. Nearly three decades later, President Ronald Reagan warned us that our schools were drifting in a “rising tide of mediocrity.” Since then, politicians have largely tilted their models towards business paradigms, believing that marketplace principles of competition, standards and accountability would break the government’s monopoly on public education and provide a fresh, anti-bureaucratic start for school districts.

The current reformers, then, are anything but iconoclasts. They are merely the latest and highest-octane participants in this movement—with a few new tools and icons on their desktop. They bring with them not only this blockbuster Hollywood documentary, but also a confluence of new money and political clout. They count among their legions of philosophical and monetary supporters high-profile education CEOs like New York City’s Joel Klein and D.C.’s Michelle Rhee (who recently resigned). They have also won the support of philanthropists like Bill and Melinda Gates, Eli Broad, the Walton Family, and Oprah. Together, these benefactors finance popular charter-school franchises like the Knowledge Is Power Program and Achievement First.

It is, to be sure, a show-stopping lineup, and it has captured the credulous attention of veteran broadcast anchors and national columnists. These are not pundits often found wandering among the tangled weeds of education policy. Some appear to be using Superman as their crash course in the subject, emerging from the theatre with a story line in hand and a fire in their belly—no questions asked.

Tom Friedman, for example, urged readers to see Superman in a Times column headlined “Steal this Movie, Too.” NBC dedicated a week to Superman in September, coinciding with the film’s release. Calling Guggenheim’s creation an “in-depth probe of public education in America,” the network sent its top anchors and senior correspondents to cover the story, blitzing town hall meetings, conducting interviews, and forming oddly one-sided panels. (One misguided segment was tentatively labeled “Does Public Education Need a Katrina?” before someone mercifully yanked it.)

Matt Lauer referenced the movie twice in his kickoff interview with President Obama for Today. CBS anchor Katie Couric, not to be outdone, wrote a blog post promising to explore several issues raised in Superman. Oprah dedicated two shows to the film and staged Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg’s $100 million giveaway to Newark’s schools—with political strings attached.

Even media mogul Rupert Murdoch delivered a full-throated policy speech inspired by Superman. “If you have not seen this film I urge you to do so,” he told an audience at the nonprofit Media Institute in early October. “[Guggenheim] portrays these rotten public schools the way we should think of them: as deadly as any heartless factory poisoning the local drinking water.”

Had these journalists probed a bit deeper, they might have been more skeptical—or at least asked better questions. A recent Stanford University study (pdf) showed only a small percentage of charter schools (17 percent) performing better than traditional schools, while 37 percent performed worse, and the rest resulted in no significant change. An analysis (pdf) of the National Assessment of Education Progress exams by researcher Richard Rothstein found that African Americans are now scoring higher in math than white children of a generation ago—without the aid of charter schools.

As for Finland, its uncanny climb from the pedagogical cellar is a tale that turns Guggenheim’s ideas upside down. Its teachers are unionized and highly trained for years at state expense. Assessment is designed by classroom teachers, not mandated by cookie-cutter exams or national standards. And all Finnish children enjoy cradle-to-grave social services, from health care to free early childhood education.

Which brings us to Geoffrey Canada, a brilliant and charismatic community organizer, but an odd choice to emerge as the voice of Superman. His groundbreaking Harlem Children’s Zone looks more like Finland than the new education reformers seem to recognize. In his book Whatever It Takes, Paul Tough describes the remarkable (and for the most part, privately funded) conveyor belt of social services Canada has created in a 97-square-block area in Harlem. The Children’s Zone provides prenatal training for parents, health care, and college prep programs—services many believe schools should not need to succeed.

By now, chinks have begun to show in the charter-school movement. Measuring the depth of a child’s education turns out to be complex and elusive. Recent reports show that even Geoffrey Canada’s schools slipped in standardized test rankings last year, along with those in other city charters.

Meanwhile, the media’s coverage of education issues remains less than inspiring. In a Wall Street Journal article, Rupert Murdoch actually suggested that we might turn to American Idol for inspiration. It has higher performance standards for pop stars, he said, than educators do for public-school children.

To be honest, nobody has zeroed in more sharply on the emptiness of such coverage than comedian Lewis Black on The Daily Show. “Ah, fall,” he intoned in a recent segment. “That magical time when we spend one or two weeks pretending we’re actually going to do something about the condition of our schools.” He then cut to a clip of David Gregory, host of NBC’s Meet the Press, providing his own DIY recipe for school reform: “If you drive by a public school, even if your kids don’t go there, walk in, and ask what you can do to help.”

It’s enough to make me cry.

Click here for a complete Page Views archive.

LynNell Hancock is the H. Gordon Garbedian Professor of Journalism at Columbia, and director of the school’s Spencer Fellowship in Education Journalism.