In the August 8 issue of New York magazine, the columnist Frank Rich suggests this takeaway from the News Corp. phone-hacking and bribery scandal: “An otherwise archetypal media colossus . . . is controlled by a family . . . that countenances the intimidation and silencing of politicians, regulators, competitors, journalists, and even ordinary citizens to maximize its profits and power and punish perceived corporate, political, and personal enemies.”

It’s true that the mafia-like corporate culture built by the Murdoch clan allows News Corp. to do or use just about anything to extend its profits and power. It’s also true that the company’s corruption found fertile ground in an equally out-of-control British tabloid culture.

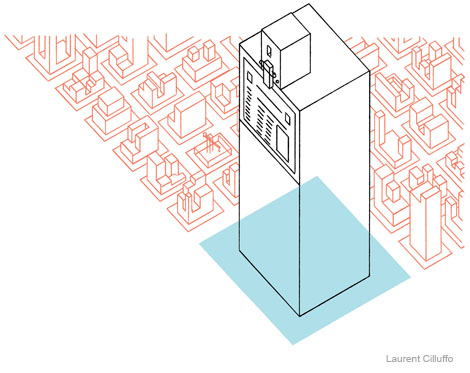

But what is essentially a throwaway phrase in Rich’s distillation—“archetypal media colossus”—is just as central as News Corp.’s thuggish disposition to understanding this story, in the UK and also here at home. News Corp.’s capacity to bully and silence comes directly from its size, from the number of media outlets it owns and the power those outlets create, economically and in terms of their ability to shape the public narrative about everything from political campaigns and policy debates to celebrity hijinks and summer blockbusters.

The deleterious effects of media consolidation—fewer voices, anemic newsrooms, self-censorship, etc.—have been argued since Ronald Reagan’s Federal Communications Commission began dismantling nearly a century of media regulation, touching off a thirty-year run of mergers and acquisitions that continues unabated.

In recent years, the case against consolidation has been tempered by the notion that digital technology has flattened the informational landscape, making everyone a potential publisher and thereby negating concerns about the fact that an ever shrinking number of companies controls an ever greater share of our news and information outlets.

But twenty years into the Internet era, most people still get most of their news—online, on-air, or in print—from the so-called legacy media, our newspapers, magazines, and TV news operations. Six companies dominate TV news, radio, online, movies, and publishing. Another eight or nine control most of the nation’s newspapers. News Corp. is on both lists.

The phone-hacking scandal is a reminder that size still matters. It comes at an opportune time. In July, a federal appeals court rejected—on procedural grounds rather than on the merits—the FCC’s attempt to further relax ownership restrictions and allow a single company to own a daily newspaper and a broadcast outlet in the same market.

We urge the FCC to retain the limit on cross ownership. It won’t solve the problem of too much power in too few hands, but it would be an important first step. There is no reason to believe the other media giants would stoop to News Corp.’s depths of cynicism, but it is naive to assume they don’t use their power in service of their corporate goals.

We also urge the commission to strengthen its public-interest standard. The obligation to provide programming that serves the public interest is part of the deal with broadcasters in exchange for the right to use the public’s airwaves. Defining what it means to “serve the public interest” is controversial, but burying newsrooms inside sprawling entertainment empires and starving them of resources is not getting the job done, no matter how you define it. A report released this summer, “The Information Needs of Communities,” authorized by the FCC itself, singles out the commission’s utter failure to enforce the public-interest standard in its license-renewal process. In the past thirty years, not one license has been denied based on a broadcaster’s failure to meet this standard.

The way to insure that good journalism flourishes is to establish structures that encourage it. A system that affords one company the power to abuse its competitors, the electoral process, and the public is not structurally sound.

The Editors are the staffers of the Columbia Journalism Review.