Andrea Bruce is a freelance photojournalist, currently based in Afghanistan, whose powerful documentary work attempts to connect people across geography and culture. In 2010, she left The Washington Post, where she had spent eight years as a staff photographer. During that period, she focused on the war in Iraq, and specifically on documenting the lives of ordinary Iraqis and US soldiers. She was one of the few Western photographers who kept going back to Iraq after 2004, when the country devolved into a brutal civil war and the risks to journalists became nearly impossible to justify. She also wrote a weekly column for the Post called “Unseen Iraq.” She has been named Photographer of the Year four times by the White House News Photographers Association, won the prestigious John Faber award for best photographic reporting from abroad from the Overseas Press Club, and was a 2011 recipient of the Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellowship. Michael Kamber interviewed Bruce in Baghdad in 2010.

Community Journalism

In my last semester of my senior year in college I took a photo class for fun, and fell in love with it and became a photographer. But my dream was never to be a war photographer. I wanted to be a community journalist. I guess there is a whole generation of us photographers who probably didn’t really think we would become war photographers until September 11. That’s how I started. I didn’t really think that it would be something I would want to do until I realized that you need community journalists in Afghanistan and Iraq almost more than you need them in the States.

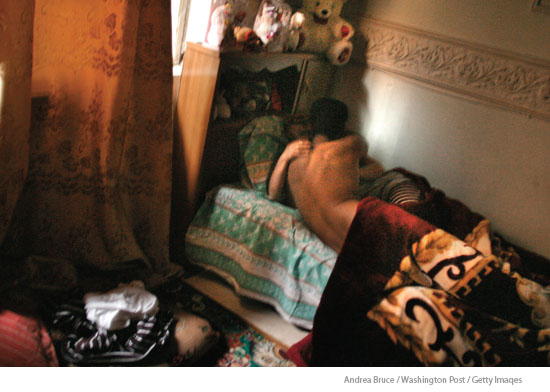

There is a story about an Iraqi prostitute that I worked on for almost a year. I interviewed almost thirty prostitutes before I found someone who was willing to talk to me. But the person I ended up following, her name is Halla, she got it. She was pretty much like, “My life sucks and I shouldn’t have to sleep with men to feed my children and so yeah, you can take pictures and show everyone exactly what is going on.” She basically became my best friend here. I’d hang out with her in between all the car bombs, in between all the embeds and violence. I would always go back to her thinking she is really what told the story to me of 2004 and Iraq. And she told it from a woman’s perspective and this war is so told by men and through men. Eventually she would just ask her customers straight up. It was very casual, they would come to her door and her children would be playing in the living room, and I’d be there, and the guys would be like, “No, I’m not going to let her photograph us.” Because I knew, that’s the one picture you had to get, to actually show why prostitution is horrible. And so one day a young client of hers came to the door and he said he didn’t care if I took pictures and so I took pictures for as long as I could handle it personally.

Waiting for the Booms

I remember just driving around, waiting for the booms to happen, looking on the horizon for the smoke, and then just driving in that direction until we found it, then it happening somewhere else, like half an hour later. And then going from the bombing scene to the hospitals, then to the morgue, and then like this almost Groundhog Day-like coverage of the bombings.

Firefights are scary, but it’s the IEDs that really kill you. It’s that suffocating feeling of being inside any kind of vehicle. I even wore my iPod I think for one year straight when I was in a Humvee because I couldn’t take it. In 2006 and 2007 it was just all the time, and you just realize that there is nothing you can do. It doesn’t matter how fast you can run or how well you can see or even if you try to figure out like, well, if I’m in the first Humvee or the second Humvee or maybe the third, which one would be the least likely to be actually hit? You just have to realize that it’s all a gamble, then you just sit there and you think, why am I doing this? And you hope that what we do actually gets seen and you hope that it actually does some good.

Sometimes I think that I totally failed. Because I don’t think any of the pictures I have ever taken have adequately shown all of that.

Some of the military would say, “Oh, you just want these pictures because you want to sell newspapers.” I’m like, “Do you know how many subscriptions were cancelled because of any photo that we ran that was even close to something like that?” Even my own mother would say, “I know this is happening but to be honest, I don’t want to see it.” You go home and you hit your head against the wall and you don’t know why you do this, but then that’s when you come back because you know that we’re probably some of the only eyes on this thing.

A Very Different Life

There’s a large toll it takes on all of us. After coming here in 2003, I got divorced at the end of 2004. I was just here the whole time. And I changed so much. I think it’s hard for me to be in the United States. Not that I dislike the United States, because I actually have a lot of pride still in my country. I find that it’s hard to be completely social. It just feels a little harder to fit in. Sometimes I get anxious. Sometimes I get bored. Sometimes I am just kind of numb. Sometimes I lose patience. In grocery store lines or with TV shows, or random things. It’s just not important or interesting to me on some level. I put everything I owned in two suitcases, everything else is in storage or sold, and I left the States. I don’t really live anywhere now. I had a house and a fenced-in yard and two dogs and a wonderful husband who is a great guy—he’s a schoolteacher. He had a very different life. When I started leaving, it kind of makes sense, he kind of felt like I abandoned him. I started to divide my life into two different realms. Like, I have a bulletproof vest, and I travel with $10,000 in my sock and, and I wear an abaya half the time and my helmet the other half the time, like some sort of deranged superhero or something. And then in the other life I am this suburban housewife. Things like doing the bills, all those things, became—it’s just that the two lives didn’t fit anymore and eventually neither did my husband. So I just think I slowly—he felt that I just wasn’t there anymore. He told me that I abandoned him.

I think things happen for that time in your life and that was the right thing for me to do at that time in my life, and this is the right thing for me to do at this time in my life. I still do think that what we do is important. This seems probably very naïve, but I love trying to bring out people’s personality in pictures and, again, I feel like I fail every time because people can be so intricate and weird and cool. So I’m like, “Oh, I have to come back and I have to do it better next time.” And so you become even more obsessed and you think, “Maybe this time I’ll get it, maybe this time I’ll take the definitive photo of the Iraq War that’ll get people to pay attention like they did in Vietnam.” I always wonder what would that photo be? This story—more than Vietnam—is so complex and different and it goes through stages, and our relationship with the military is weird and the war itself is more removed than it was in Vietnam. Now, soldiers can fire bombs at people from so far away that it’s almost not personal in many ways. I guess the definitive photo so far would be the pictures soldiers took in Abu Ghraib. Because they show the reality that no one wants to really admit, which is that the relationship between the US and the Iraqis that they are supposed to be liberating was not quite so cheery.

He’s Going to Fucking Kill Me

People are more scared of cameras here than they are of guns. I always wonder if the Americans’ fear of journalism and journalists has actually kind of become the Iraqis’ fear of journalists and cameras. I can’t even carry a camera down the street these days without someone from the Iraqi military stopping me and harassing me. I showed up at a car bomb scene and it started getting so violent. They would push you, smack you. Someone took a piece of metal and swung it at me. I mean, I have been slapped. It’s been insane. In 2005, there were several suicide bombings, one after another, one day in Karbala. We hear the bombs going off and myself and the reporter, of course, our initial reaction is to take pictures. I wasn’t with the military. I was dressed in an abaya. That’s just how I deal with it, and it was horrible—the bombing scene, blood everywhere and people being carted off in wheelbarrows with no legs and just like hell. I started taking pictures and before I knew it I was lifted off the ground and pinned against a wall, and there was one person and he was screaming at me and I remember the look in his eyes like, “He’s going to kill me, he’s going to just fucking kill me,” because they are just so upset, they just saw tons of people reduced to nothing. And there was one person doing this and suddenly there were just fifty people doing that to me. That whole mob mentality. And luckily, I was with a reporter who spoke Arabic and he told them, “She’s my wife, she’s my wife, you have to respect her.” And slowly, that humanized me to some extent; so slowly, after a lot of talking, they let me go. That was probably the scariest thing that has ever happened to me—“You have a camera, you are the reason why this is happening, so we are attacking you.”

It wasn’t that way in 2003 or ’04. I remember people wanting me to take pictures of car bombs because they were like, “This is freedom, this is what the Americans are bringing to Iraq!” And then, suddenly, the media became the problem and I don’t know how or why that happened exactly. After talking this mob down, the reporter and I walked away and it took another half hour to get my cameras back, which we did, which is unbelievable. There was some kind man in the crowd who helped us. And then we walked away and the guy who initially grabbed me found us again and I was like shaking at this point, I couldn’t, I couldn’t think. And he grabbed us and he was like, “I understand now, you’re journalists, you must take pictures of this.” And so he grabbed us and he took us around for an hour, and made me take pictures of every little piece of flesh. Or like a tooth. Or an eye. Or brains. Which is just as traumatic almost. I was like, “No one is going to use these pictures,” and I am taking pictures of all the little tiny bits of body parts, under the supervision of this guy who almost killed me. It was just the craziest thing. To this day, I hear a bombing and I barely go out to cover it.

No Regrets

The military really is a guy culture. And they almost don’t know what to do with us [women] when we embed with them. And you’re stuck in like, supply closets, living by yourself. Or with some FOBs that are actually dangerous. I have had to live in tiny, half-fallen shacks. Far away from where all the men are, no sand bags, in the middle of nowhere. I mean, it’s tough for women in Iraqi culture, too. I’ve had men slap me and tell me, “Woman, no.” Actually, quite a few times I have had [American] guys on embeds flat out tell me, “You’re a woman, you shouldn’t be here.” Female soldiers aren’t allowed on the front lines. But we are. We’re the only women on the front lines of any war. It’s kind of incredible. And as a photographer, we’re right there up front. I have had to earn the trust of people. I have to prove myself to be hardcore, that I can actually do it. I have probably more experience than most of the guys. But also, they won’t respect you if you completely give up your femininity. So you can’t be like completely butch. I am just kind of a shadow or something.

Some people look at us women and think that we have somewhat sad lifestyles. But I’m kinda like, “Are you kidding me?! This is the best life!” We see the most amazing things, we meet the most amazing people. I guess it’s the whole marriage-baby thing that makes people think that, but I have no regrets.

Michael Kamber is a contract photographer and writer for The New York Times who has chronicled many of the world’s major conflicts over the last decade. His interview with Bruce is part of his forthcoming book, the working title of which is Uncensored: A Photojournalists’ Oral History of the Iraq War. It is due out in 2012 from the University of Texas Press.