A strange thing happens when you turn on the news in Hawaii. Tune into the 10pm local newscast on KGMB, the Aloha State’s CBS affiliate, then switch to its supposed NBC competitor, KHNL. Then go back and forth again. You will see the same stories, the same footage, the same broadcasts from beginning to end. Every weekday, for three hours, the two stations simulcast the news. A third station, KFVE, is also not much of a rival, airing 11 hours of news each week that is produced by the same Honolulu newsroom as KHNL and KGMB. Three of the five stations that deliver daily TV news in Hawaii have been joined into a single news operation.

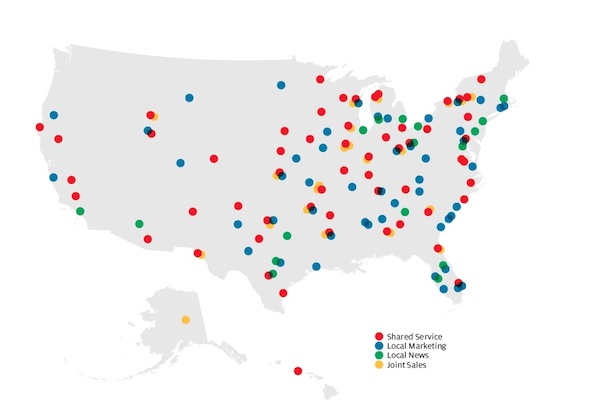

The three-way partnership represents one of the more striking examples of a rapidly growing phenomenon in local TV news: joint-services agreements. These deals allow different stations in the same market to pool resources. Nationwide, at least 126 joint-services agreements are in effect, covering 99 of the 210 television markets in the country, according to a University of Delaware study. The number has climbed rapidly; a similar study in 2011, just two years earlier, found only 83 markets affected.

What is the problem? In some cases, there is none. The deals vary widely from agreement to agreement, and often include only marketing or sales teams, which seems harmless enough. But many include sharing news operations. A subcategory of joint-services agreements–currently 55 of the known 126–are called shared-services agreements, and they always involve the sharing of newsgathering resources. The resources shared can vary from news scripts and story packages, to reporters and the merger of entire newsrooms–so that communities end up with fewer local voices, less information overall, and only the illusion of choice. News outlets, meanwhile, can end up with more power than the spirit of Federal Communications Commission rules on media consolidation would seem to warrant.

For decades, the tendency in the television industry has been toward consolidation–fewer and fewer owners with more and more power over what we get as news. Congress and the FCC have long tried to temper this trend by regulating ownership and market limits. In calculating the limits, though, the FCC has chosen not to include most joint-services agreements: Only marketing and sales agreements covering more than 15 percent of a station’s advertising time are attributed toward the limits, while the crucial news-oriented deals, shared-services agreements, are exempted entirely. Critics see this as a big loophole: While the FCC limits consolidation, it turns a blind eye to a trend that has very similar effects.

In Hawaii, back in 2009, an advocacy group calling itself Media Council Hawaii argued to the FCC that the consolidation of operations between the three Honolulu news operations, in effect, violated rules limiting a single company’s holdings in a single market. FCC rules prohibit one company from owning more than one station in the same market, with a small number of exceptions, such as if the two stations’ service areas do not overlap (none of these exceptions applied in Hawaii). The FCC examined the case, and staff members report having serious misgivings about the deal.

But ultimately, the commission decided that it could not reject a shared-services agreement for violating ownership limits because no broadcast license had changed hands. Its 2011 ruling on the matter stated that “further action on our part is warranted with respect to this and analogous cases” to determine if such deals are “consistent with the public interest.” But it has not followed up with any such action.

“One of the questions that I’ve always had is, where is the FCC in all of this?” says Bob Papper, the chair of the journalism department at Hofstra University and an expert on local television news. Papper said he supports joint-services agreements in some cases, but that others, such as the Hawaii deal, appear to plainly violate the intent of ownership limits. “If the regulator isn’t regulating, then I’m not sure where we are,” he said.

Dumbing down the dialogue?

The growth of joint-services agreements is occurring at a time of very rapid overall consolidation in the local broadcast industry. The last few months alone have seen the Tribune Company purchase most of Local TV’s stations, Gannett Company purchase Belo, Media General merge with New Young Broadcasting, and the behemoth Sinclair Broadcast Group purchase Fisher Communications. Industry executives have predicted that within five years or less, local broadcasting will be dominated by a three or four “super groups,” while smaller companies are swallowed up or go out of business.

Seeing double Or even triple. TV news outlets in 99 of the nation’s 210 television markets have some type of joint-services agreement under which they share resources, from reporters to video to entire programming lineups. (Danilo Yanich)

According to television news experts, such mergers and acquisitions can lead to more joint-services agreements via a self-perpetuating cycle: Acquiring new stations leads companies to take on debt. Debt, in turn, provides powerful incentive to cut costs in the newsroom. And joint-services agreements are tailor-made for that.

Media policy advocates fear that this cycle is reducing the number of voices among local broadcasters, which remain Americans’ leading source of local news. “Localism has suffered and the quality of our news and information has suffered,” says former FCC Commissioner Michael Copps about industry consolidation and the spread of joint-services agreements. “I don’t think we have the luxury of having another two or three years of dumbing down our civic dialogue, and expecting that the American people will be informed.”

On the other side of this debate are broadcasters, who argue–just as adamantly–that joint-services agreements have the opposite effect: improving both the quality and accessibility of local news. They note that the deals sometimes allow small stations without the capacity to produce their own local news to air news programming. During the recent recession, say broadcast industry groups, the agreements were sometimes lifelines for struggling stations. “We don’t see anything inherently bad about two stations sharing, for example, a helicopter,” says Dennis Wharton, a spokesman for the industry group National Association of Broadcasters (NAB). “Ultimately, if there’s a lessening of the standards viewers expect, they’ll be the final arbiters.”

In an address last February at the FCC Media Institute Luncheon, Ajit Pai, a current FCC commissioner, took a strong stance against the argument that stations should count these agreements toward media ownership limits in individual markets–a decision that would likely put an end to most joint-services agreements. “If the FCC effectively prohibits these agreements, fewer stations in small-town America will offer news programming, and they will invest less in newsgathering,” Pai said. “And the economics suggest that there likely will be fewer television stations, period.”

The NAB, meanwhile, contends that much of the opposition to joint-services agreements is driven by forces far less altruistic than media reformers concerned about diversity of ownership. Wharton, the group’s spokesman, says that paid TV companies such as cable and satellite TV providers have a major stake in the fight, and are seeking to weaken the viability of the broadcast industry. Paid TV giants, such as Time Warner, dish Network, and DirecTV, “want to get rid of competition that is free,” he says.

Broadcasters also argue that sharing resources saves jobs, although that case is harder to make. Jobs in TV news seem more tied to the overall economy than anything else. The number of jobs in local television news plummeted during the recession, but that number has sharply recovered recently. By 2012, according to Hofstra’s annual survey, local news set a record for full-time employment, with 27,653 jobs.

The inherent nature of the joint-services agreements, their critics say, is to reduce jobs. And now that the industry is booming again–with strong job growth and a rush of mergers and acquisitions–advocates argue that there is no longer any excuse to tolerate the agreements for reasons of economic necessity. And some of the agreements have indeed resulted in substantial job losses, according to news reports cited in studies by the University of Delaware: 68 jobs lost at the Hawaii stations; 27 jobs lost in an agreement in Idaho Falls, ID; 15 jobs lost in Providence, RI, for example.

Since the FCC doesn’t track them, most of what we know about joint-services agreements comes from those University of Delaware studies–information painstakingly gathered from news reports and surveys of stations by a professor, Danilo Yanich. After the Hawaii deal went into effect, Yanich and his intrepid students compared the content of the news aired by the three stations involved before and after the agreement. He found that the quantity of unique story topics on each station dropped sharply, while the amount of shared subject matter–meaning coverage of the same story, such as a crime at a particular address–more than doubled. During a weeklong period before the deal, the three stations ran 53 stories on topics addressed exclusively on one station and 76 stories on topics that were addressed by more than one station. During a similar period after the agreement, the stations ran only 19 stories on a topic covered exclusively by one station, and 157 on topics covered by multiple stations. (It is worth noting, however, that the total number of stories on the stations increased after the deal.)

Another study by Yanich of eight joint-services agreements in markets across the country found similar results. Among the stories with shared content on the partnering stations, most had the same scripts, the same video, or both.

A right to know

Just as the FCC does not track joint-services agreements, it has declined to conduct research into them. At one point, when it was commissioning research for its (still unfinished) 2010 quadrennial review of media ownership rules, the commission ordered studies be conducted on 11 ownership-related topics to inform its new rules, and commissioner Copps pressed for the research to consider joint-services agreements.

But he lost that round. A former FCC staffer, who asked to remain anonymous, said that during the process the NAB lobbied heavily to prevent joint-services agreements from being addressed. “They were very adamant that we not include it as part of the quadrennial review in terms of ownership,” the staffer said. (The FCC declined to comment for this story.)

President Obama has nominated Tom Wheeler–a campaign bundler and former lobbyist for cable television companies–to become the commission’s next chairman. The FCC is unlikely to take action on ownership rules before Wheeler’s confirmation, which is expected to be approved but as of press time is pending before the Senate.

Meanwhile, the agency’s passivity on joint-services agreements has begun to attract some attention. In June, Senator Jay Rockefeller, a Democrat from West Virginia, released an open letter to the Government Accountability Office, urging it to examine whether the agreements violate ownership limits. The letter also calls on the gao to examine whether the FCC could begin requiring public disclosure of the deals.

To some, the lack of information about joint-services agreements is the worst part. “I think people should be concerned about the lack of information,” said Steve Waldman, a former FCC adviser. “The public has a right to know much more about these arrangements.”

Waldman supports the idea of joint-services agreements in some situations. But, he said, the lack of information about them makes it impossible to determine which agreements reflect sensible attempts at efficiency, and which are driven by cost cutting and outsourcing. “The promise of shared services agreements is that we’ll use shared services to eliminate duplicate investment, and then we’ll invest them in investigative reporting and boots on the ground,” he said. “And that isn’t what happened. It’s evolved in some cases into outsourcing the news.”

Sasha Chavkin is an investigative reporter specializing in the environment, Latin America, and public corruption. He was the lead reporter for OCCRP's "Nicaragua's Forgotten Deforestation Crisis" investigation, and is currently a 2021-22 Ted Scripps Fellow in Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado at Boulder.