Her time Jessica Lum was a journalist for the new century, an empathic reporter who told timeless stories with digital-age tools. (Courtesy of the Lum family)

On September 22, 2012, Jessica Ann Lum took the stage to accept her award for Best Feature in the student-journalist category from the Online News Association. As the lights in the San Francisco Hyatt Regency’s Grand Ballroom glinted off the silver sequins on her shirt, Jessica gave a “brief and SEO-friendly” acceptance speech, as host Hari Sreenivasan, the PBS NewsHour correspondent, had requested.

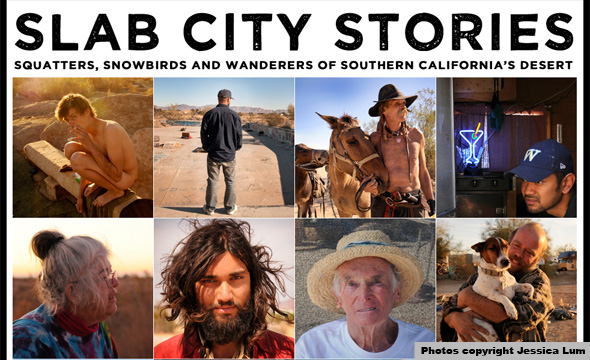

Jessica hadn’t expected to win. The other finalists were teams of students, and she worked solo on her “Slab City Stories” project–a multimedia report on the inhabitants of a former Marine base-turned-squatter-RV-park in the California desert (though not, she made sure to point out, without the support of her professors, classmates, and Kickstarter backers). Jessica didn’t enjoy being in the spotlight, either; she was more comfortable behind the camera than in front of it. It took her only a few seconds longer to accept the award than it did to get to the stage. After a rush of thank-yous and a celebratory double fist-pump, Jessica returned to her seat–and to what appeared to be a bright future, one in which she’d tell many more stories and win many more awards.

Less than four months later, on January 13, 2013, Jessica died. She was 25.

As a college senior, she’d already decided that she was going to be a journalist who told people’s stories honestly and powerfully, using words, photos, videos, and design; and that nothing–not the recession, the bleak journalism job market, nor the rare, incurable cancer with which she’d just been diagnosed–would stop her. According to her family, friends, professors, classmates, and colleagues, Jessica was that determined and that talented–and she was right. Jessica’s tragically brief journalism career is significant not only because of the substantive work she produced, but because of how she did it: firmly rooted in the fundamentals of reporting and storytelling, but with a vision and style that incorporated today’s digital tools. She was, in many ways, the future of journalism. Jessica loved to tell people’s stories. This is hers.

Jessica’s ONA trophy–a clear acrylic pyramid–sits on a mantel in her parents’ house in Sacramento’s South Land Park neighborhood. This is where Jessica and her older sister, Bethany, grew up, and where her parents, Bob, a retired high-school physics teacher, and Anna, who worked for the state as an analyst before retiring in 2007, still live with their dog, Dakota. Dakota is a recent addition to the family; Anna relented on her no-dogs rule when she realized this was Jessica’s only chance to have one. She asked only that the dog Jessica brought home from the Sacramento SPCA not be big or black. Dakota is a black German Shepherd mix. “This is the one she fell in love with,” Anna says with a laugh.

From an early age, Jessica displayed many of the traits that would define her journalism: curious, adventurous, intelligent, determined, fearless, compassionate. As a newborn, she surprised nurses by grabbing onto the side of her bassinet and trying to pull herself up. The Lums would see this determination countless times thereafter. “If she wants to latch onto something, she’ll stay there,” Bob says.

Growing up, Jessica was a tomboy who preferred Transformers to dolls; this made fitting in with other children difficult at times. By junior high, she’d found her way socially, though she always had a soft spot for outsiders–from homeless people, to whom she would occasionally give her lunch (and the Tupperware it was packed in), to a lonely new student from Taiwan who became a lifelong friend.

She stood 5’ 4.5″ and typically wore T-shirts and jeans. She loved to snowboard and was a self-described “huge nerd,” with Dragon Ball Z posters on the walls of a room that looked more like a 10-year-old boy’s lair than a teenage girl’s. She played video games and ate Korean BBQ, usually with her fiancé, Chris Tanouye.

Although she was a voracious reader, she was not really a news junkie. Her father, though, could sometimes convince her to watch the news with him. PBS NewsHour was a family favorite, and when Jessica recognized one of its regular commentators on a San Francisco street, she had her picture taken with him. The photo, now framed, shows a smiling teenager next to a happy–if a bit surprised–Mark Shields.

Her high school had links to prominent journalists–it was named after C. K. McClatchy, and Joan Didion (who would later become one of Jessica’s favorite writers) is an alum–but it wasn’t until her senior year that she got interested in journalism. Jessica enrolled in a photography class at a local community college, taking black-and-white pictures on a 35-millimeter Minolta X570 that was older than she was. Despite her inexperience, many of the photos she took then display characteristics of the more sophisticated shots she took later on: buildings at unconventional angles, an emphasis on symmetry and recurring patterns, evocative lighting. Her love of photography prompted her to join UCLA’s campus paper, The Daily Bruin, soon after arriving for her freshman year.

Robert Faturechi, a colleague at the Bruin, recalls working with Jessica on stories, he as the reporter and she as the photographer. “She really wanted to get to know the people, the subjects, the topic–everything,” says Faturechi, now a reporter at the Los Angeles Times.

In the summer of 2008, she and Faturechi won a traveling scholarship, and spent two weeks in Thailand reporting on the effects of the HIV/AIDS epidemic on children and sex workers. Faturechi remembers Jessica’s ability to connect with everyone, from Wik, an HIV-positive orphan, to Bill, an American she met on a long train ride who was very open about his fondness for Thai prostitutes. “I don’t want to be judgmental, but he was a creepy guy,” Faturechi says. “But Jess was not fazed by that.” She would later write that the man made her “uneasy,” but told her mother that she never saw her subjects as anything less than human beings to be greeted with an open mind and genuine interest.

The resulting series, published in The Daily Bruin, reflects the effort she put into that kind of reporting. Whether portraying Wik, nasal cannula in place and arms wrapped around an orphanage worker, or a rain-soaked alley that leads to the Classic Boys Club, the photos vividly evoke the locations and people they depict.

Jessica also wrote about how her perception of photography and journalism was shaped by the trip. “We often assume that a single photograph can encapsulate an entire life, a whole idea, or a whole person,” she wrote. “And yet, as iconic as photographs can be, they often fail, just as words fail, to achieve such lofty goals. . . . Words and images must work together in order to tell a whole story.”

During the trip, Jessica mentioned to Faturechi that she felt tired and rundown. She didn’t think much of it, as they were working long hours on little sleep in the hot Thai summer. But by the time the series was published in early December 2008, Jessica still felt sick; she had pain in her hip and back, and kept getting chest colds. She wondered if she’d caught tuberculosis in Thailand. Her doctors were puzzled until she mentioned a “little bump” on her abdomen. Pheochromocytomas, tumors of the adrenal gland above the kidney, are rare, occurring in between two and eight people per million each year. Of those, only 10 percent are malignant.

On Christmas day, 2008, Jessica posted on her Facebook wall: “I have Cancer + 10 questions you might ask.”

The cancer had already spread to her bones; her hip, she later wrote in Giant Robot magazine, “looks like a coral reef.” A picture of her tumor, that she insisted her surgeons take after they removed it, accompanied the article. It was a pink-and-white knot about the size of a grapefruit. Jessica described it as “freakishly mesmerizing.”

She left school a semester early, moved back home, and looked into treatment options. Without treatment, her doctor gave her two years. With it, he told her, “more than two years.” For once, that’s where Jessica’s curiosity stopped. “After that, she didn’t want to know how much time she had,” Anna says. “Even toward the end, she didn’t want to know. Although she knew. She knew it was close.”

There was oral chemo and three rounds of an experimental radiation therapy that required her to spend 29 days in a hospital isolation room, where she slept behind a lead shield. The radiation treatment was risky; some patients had died from it. But the gamble paid off, and the cancer stabilized. Jessica felt better and was ready to “resume plans that had been derailed.”

She started working again, as co-editor of the photography blog PetaPixel and photo editor at Hyphen magazine. And she applied to grad school. She was determined to be a journalist, and thought the skills and experience she’d gain there would be the best way to accomplish this. Her parents weren’t so sure. Anna encouraged her to stay in Sacramento, get an office job, and “focus on getting her health back.” Jessica responded, “Mom, this disease, it’s gonna get me anyway. And so while I’m feeling well I want to be able to live life. Be able to pursue my dreams. However long I can.”

She removed all references to her illness from the Internet. Jessica would later say this was for “professional reasons”–she was afraid employers wouldn’t hire someone who was sick–but she also chose not to tell her professors or classmates. She didn’t want pity or special treatment.

Jessica began at UC Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism in fall 2010. She was interviewed by one of her professors, Richard Koci Hernandez, as part of a video about the first weeks of school. She looks happy and healthy and energized. “What does journalism mean to you?” Koci asks. Without hesitation, Jessica answers, “It means storytelling at its deepest level. At its most human level, I think, in a very real way.”

She thrived at Berkeley. Professors describe her as “pretty phenomenal,” “immediately terrific.” Classmate Hadley Robinson remembers her as a “social-media addict” who was “interested in how journalism is evolving,” what it would and could be. “I was impressed by her right away,” Robinson says.

Rainy days Jessica worked at Berkeley’s Mission Loc@l during both years of grad school. She wrote, photographed, edited, and coded for the site. (Jessica Lum / Courtesy of Mission Loc@l)

Jessica enrolled in a class called “Digital TV and the World,” the description of which seemed tailor-made to her interests: “new styles of global reportage that take a close-up look at ordinary people and the issues they face.” That semester, the class focused on South Korea, and spent a month reporting from inside the country. Their work was published in a special section of The Washington Post‘s website that Jessica designed and produced. Two of Jessica’s video reports are featured, including “The Return,” about a schizophrenic woman who makes weekly visits to the mental hospital where she was once committed to teach the patients who are still there.

The access Jessica got to the woman is testament to her ability to connect with people. “She actually went in and was filming in an institution,” recalled her classmate, Anne Brice. “That’s really hard to do, especially in Korea. It’s a very taboo subject.” The woman invited Jessica into her home, allowed her to film her brushing her teeth (one task the woman said her illness still made it difficult for her to do) and celebrating her 64th birthday. Jessica narrated the video: “It’s one more year she’s lived–on her own terms.”

As soon as she returned from South Korea, Jessica began an internship at the LA Times. By August, she was itching to escape LA for a while, and organized a road trip with some co-workers into the Colorado Desert in southeastern California. One stop was Slab City and its itinerant population, which typically shuns the outside world.

It was more than a hundred degrees when Jessica first got to Slab City; she didn’t stay long, but found herself wondering who lived in the RVs, and why they chose to stay in such inhospitable conditions. She returned in October, when it was cooler and many of the part-time residents had returned. “I just felt like this was a place that I could meet really fascinating people with great stories,” she later said.

Most “Slabbers,” as the people who live there are called, have become reluctant to talk to a media that often portrays them as “weirdos, hippies and drug addicts inhabiting the lawless patch of the California desert,” as a headline in UK’s Daily Mail put it. Jessica saw an opportunity to take a different approach.

To do this, she’d need to spend enough time with the Slabbers to earn their trust. Neil Mallick, an artist she would eventually profile, remembers first seeing Jessica around Halloween, “just hanging out,” with a camera at her side but no “reporter vibe,” as he put it. He saw her again in December, when she rented an RV and lived among the Slabbers for three weeks.

Mallick described Jessica’s reporting as an “anti-process.” More likely, her approachability and genuine interest in her subjects masked that process, which was just good beat reporting. She frequented Slab City’s Oasis Club (“where the old-timers go,” Mallick says), drank coffee with them at the solar-powered Internet café, and attended community meetings. She ended up profiling a variety of people, whose lives she documented through photos, videos, and notecards she had each of them fill out. She filmed Karen Webb bathing nude in Slab City’s hot springs, and Justin Davis, a 36-year-old reliving his lost teenage years in the skate park he built in an abandoned swimming pool. She photographed “Cuervo,” “houseless on muleback for 15 years,” and chronicled the 80th birthday party of Leonard Knight, the artist who created “Salvation Mountain,” a 50-foot-high, cross-topped clay mountain that is Slab City’s most prominent landmark.

When it was time to put the project together for the website she designed and coded herself, Jessica let the dynamic personalities shape the look and feel. Visually, it’s minimal, with a simple grid of 16 boxes. Click on a box and a window pops up with more information. Sometimes it’s just a picture and an index card, usually written by the subject himself–a design element that gives the digital page a real-world feel. In a few cases, there’s a video. There’s very little about Jessica herself, which her professor, Jeremy Rue, says was intentional. She also chose to headline the page with a simple sentence: “Squatters, Snowbirds and Wanderers of Southern California’s Desert.” People who come to the site, much like the people who come to Slab City, can explore and figure it out for themselves.

Slab City Jessica’s award-winning Master’s project looked simple, but used multiple media formats to tell the stories of fourteen Slab City residents.(Jessica Lum / Courtesy of the Lum family)

Jessica had learned that her cancer had returned in October 2011, just before she was scheduled to make her first reporting trip to Slab City. She went anyway. By her final semester, however, the disease was taking its toll. There were more frequent doctor’s appointments, but she still didn’t tell her classmates or professors what was wrong, alluding only to “health problems.”

Jessica was determined to walk at graduation, though she was in so much pain she wasn’t sure if she’d be able to. She did.

“She finished strong,” Anna says.

“She finished strong,” Bob repeats.

But Jessica wasn’t finished. KPCC, a Southern California public-radio station, was expanding its multimedia team. Grant Slater, one of the station’s visual journalists, came across Jessica’s work and reached out to her. “I was really impressed by her roundness as a journalist,” he says. “It’s not often that you get somebody right out of grad school who can speak to all these mediums.”

She moved to Los Angeles and began work–and more chemo. The treatment made her sick; she struggled to finish her first assignment. She drove herself to the emergency room, and a doctor there told her to go back to Sacramento.

About a week after she started at KPCC, she told her new co-workers that she had “health issues” and had to move back home. They wouldn’t find out how serious it was until a few months later, in August, when Jessica started talking about her condition on Facebook again, with a post that shocked classmates and colleagues who weren’t aware of her illness. “Friends, I am not doing well,” she began. Her lungs were filling with fluid. Her heart had stopped; she was in the hospital when it happened, and was resuscitated. But it was time, her doctor said, to go into hospice. Chris Tanouye, Jessica’s first boyfriend whom she met during their freshman year at UCLA, proposed to her at her hospital bedside, according to the Daily Bruin. Anna describes him as “totally devoted” to Jessica, especially at the end. He declined to be interviewed.

Unusually, Jessica’s condition improved for a short time, and she was able to go off of oxygen. She brought a tank with her to the ONA banquet–which she was determined to attend, of course–though she never needed it. Slater saw his former hire in the lobby, “radiant and beaming,” but “I could tell she was not having the easiest time of it,” he says. “Things happened really quickly after that.”

In her final days, Jessica wrote that she was “looking forward to 2013, in spite of the guaranteed unknowns, thankful I can still say that.” She watched series finales of her favorite sci-fi shows and took photos of dessert: “I am going to eat this small stack of Oreos, no regrets.” Her mother read her a passage from Randy Alcorn’s Heaven. Jessica asked her to read it again and again. In one of her final Facebook posts, she told her friends she felt “at peace. This life is not the only one to be lived. All good things . . . ,” and she signed off the same way she did in 2009, on her last post before she began isolation treatment:

“See you on the other side.”

In Giant Robot, Jessica wrote: “it’s one thing to survive, and another to live.” It is another thing again to live on. Anna is thinking of writing a book; she’s always liked writing, and Jessica left behind several empty journals and notebooks she might as well try to fill. Jessica left a copy of a favorite book, Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking, on her dresser. Anna says she’d like to read it someday.

Jessica’s sister, Bethany, moved to Africa with her husband and three children about a month after Jessica died. She took Jessica’s Nikon D300s with her. Jessica always wanted to take pictures of African animals; Bethany plans to learn how to use it and take a few for her.

Maya Sugarman, one of Jessica’s UCLA classmates, filled her job at KPCC. “She was always a role model to me,” Sugarman says. “In a lot of ways, I feel this duty–and a lot of pressure, really–to make pictures that Jess never will be able to. They’ll never be the same as the ones she could have made.”

John Osborn, a year behind Jessica at Berkeley, is working on a news-related video game for his Master’s project. There is a journalist character who looks a lot like Jessica.

Jessica’s journalism will live on, too, as a record of a talented young reporter who could bridge old media and new, and in those who are inspired by her–journalists who can visualize and produce projects from beginning to end, from the first question to the last line of code. At the next graduation, UC Berkeley will name an award after her for work that shows excellence in visual journalism in a digital environment. Jessica, her mother says, was a “lifelong learner.” We can learn a lot from her–from the work that she did, and from her drive to do it.

Click here to see more of Jessica Lum’s work.

Sara Morrison is a former assistant editor at CJR. Follow her on Twitter @saramorrison.