Big job Joseph Makkos sits amid a mountain of historically important newspapers. (Zack Smith)

Joseph Makkos lives in a modest, second-floor studio in a light-industrial area of New Orleans’ Ninth Ward, where his living space competes with his passion for printing. His bed is stuffed in a nook beside three different turn-of-the-century printing presses, and the floor is cluttered with drawers and buckets full of small letters and numbers made of lead. In the studio’s center leans a tall wall of clear plastic tubes, each containing original, Victorian-era copies of New Orleans’ daily newspaper, known since 19151914 as the Times-Picayune. In a vast warehouse space below Makkos’ room, hundreds of tube-filled cardboard boxes await unpacking.

Makkos estimates that he has 30,000 sections of the Picayune, covering 1888 to 1929–an especially important period in the paper’s history and the history of news technology in general. “I just found it while trolling Craigslist,” says Makkos. “An ad in the ‘free’ section that said ‘historic newspaper collection.’ It had pictures of the giant stacks in a storefront, and some images of the tubes.”

The papers’ previous owners have included Pennsylvania newspaper dealer Timothy Hughes, who won them in a 1999 British Library auction in which he outbid author Nicholson Baker, as detailed in Baker’s book Double Fold, an indictment of the routine destruction of old newspaper archives and books by libraries. Makkos learned almost everything he knows about his own collection from Double Fold and hopes his work will serve as a sort of coda to it. The book claims that, while part of the British Library’s collection, Makkos’ Picayunes survived an attack by Nazi pilots who bombed the library, mistaking it for munitions storage or a warplane factory. More than 10,000 editions of Irish and English papers were destroyed. The surviving papers were housed in the British Library and Museum in northern London until Hughes bought them, later selling them to an anonymous buyer who, remaining anonymous via a property manager, finally gave them to Makkos.

With the collection overflowing his studio, Makkos brushes against history with every step. He unsheathes an edition from April 6, 1914, bearing mastheads from both the Daily Picayune and the Times-Democrat simultaneously–a style worn only briefly, right after the papers merged that same year. The paper’s masthead changes three times within Makkos’ collection, starting out as the Daily Picayune, then merging with the Times-Democrat, before officially becoming the Times-Picayune, a name that will celebrate its centennial in 2015this year.

He hands me another tube dated April 6, 1914, which features a political cartoon referencing New Orleans’ discontent at being passed over for a Federal Reserve branch “even though the city hosts a US Mint. That was a big political issue,” Makkos says. He grabs another random paper: January 23, 1901, the Victorian era meets the beginning of its end with the headline, “Queen Victoria is Dead.” Another, from early July 1929: “The paper from the day before, July 3, includes the announcement telling the New Orleans transit workers that, ‘Work must resume!’ ” Makkos chuckles because the next day’s headline, July 4, reads, “Car Man Shot as 1000 People Battle in the Canal St Bus Barns.” Makkos believes that particular paper documents the exact origination of New Orleans’ traditional po’boy: “During the strike,” Makkos says, “the owners of Mothers restaurant on Willow, around where the riot was, gave out sandwiches to the striking workers, like, ‘Give that poor boy a sandwich.’ ”

Makkos plans to preserve all this history and, in some cases, bring it back to life, using his hand presses–of the same vintage as those used to originally print the papers–to create photo replicas, broadsides, chapbooks, and other literary art objects based on his collection of Picayunes. But first he wants to organize and archive the massive collection. This could take years. He has started sorting a trail of tubes across his futon that represent Mardi Gras coverage; another wall is stacked with Victorian-era cartoons, political and otherwise; beside that leans a tower of Sunday magazines bearing the British Library’s red cancellation stamp. Makkos says that many of these bound editions from the British Library were probably complete and intact.

But he is perturbed that, outside of what’s in his room, these papers now exist only on the same type of microfilm he used to browse in his elementary school library. The paper’s official microfilm archives were likely created from newspapers still in their bindings, which hindered the scanning process, according to Nicholson Baker’s book. Once Makkos determines the best technology, he will begin archiving the collection to create what may well be the clearest, most complete record of historic Picayunes.

Innovator The Eliza Jane Nicholson Collection’s women’s fashion section (1914). (Image courtesy of NOLA DNA)

before he acquired the papers, makkos had already been an admirer of Eliza Jane Poitevent Holbrook Nicholson, a poet and businesswoman at the forefront of Victorian journalism. Growing up in Mississippi, she’d published pastoral, earthy poetry in the Picayune under the pen name Pearl Rivers. A member of the first wave of female journalists storming the newsrooms, according to KnowLA, an online encyclopedia of Louisiana history and culture, she became literary editor of the Daily Picayune in 1870. Within two years she married the Picayune‘s much older owner, Colonel Alva Holbrook, who died four years later, in 1876, making his widow the first female publisher of a daily metropolitan newspaper in the country.

At that time, the paper was in debt and underperforming financially, but Picayune business manager George Nicholson purchased a portion of the company as a show of support for his young, trailblazing boss. In a further show of support, he then married her. Eliza Jane Nicholson’s content innovations and George Nicholson’s business skills made the Picayune into a powerful ship that the couple expertly navigated through the end of Reconstruction, the yellow fever outbreak, and the 1893 Cheniere Caminada hurricane, as Lamar W. Bridges recounts in the journal Louisiana History. Makkos’ archive picks up about 10 years into their marriage, and he has taken to calling it “The Eliza Jane Nicholson Collection.”

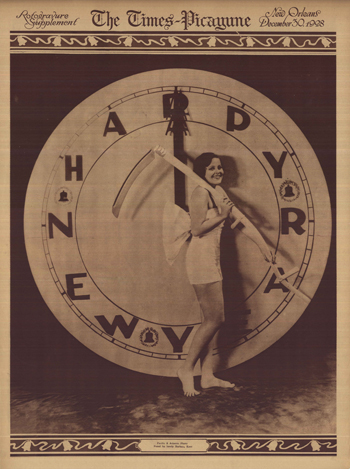

Innovator The Eliza Jane Nicholson Collection’s New Year’s edition (1928). (Image courtesy of NOLA DNA)

Nicholson, realizing that women were an underserved audience, broadened her editorial tradition of offering poetry, and literary and romantic stories. She expanded the Picayune from one eight-page section focusing mostly on power and money, giving it a second, more female-oriented section just as suffrage began to bloom. Her new “Section 2” included book reviews, articles about animals, columns about health, and a women’s advice column by Dorothy Dix. Nicholson published the first weekly issue of a serial novel called A Dead Life, and Makkos reaches into his pile to show me a syndicated Sherlock Holmes story from 1905. “That wouldn’t have happened without Eliza Jane,” he says.

“The back of the second section was a children’s page,” Makkos says, showing me the copy. “So the family are all reading the paper together, and dad hands mom her section, then mom tears the back off and throws it to the kids.” The new section’s front page typically featured Nicholson’s most notable editorial innovation: Society Bee, a local column she wrote, sans byline, covering Mardi Gras krewes and other high-end society news. “That idea was first rejected by the Uptown crowd, because they felt it would be invasive,” Makkos says. “But Eliza Jane won them over, and the column became a big deal, like, ‘We’re celebrities now because our names, and even our photographs, are in the paper.’ ” The paper went on to add a sports page, a magazine, and more prominent visuals, transitioning from illustrations into the age of photography. The earliest photo Makkos has found so far dates to 1900, four years after Nicholson’s death and some 20 years after the New York and Chicago papers had started running photography. Somewhere among of all his tubes is the first photograph ever published in the Picayune.

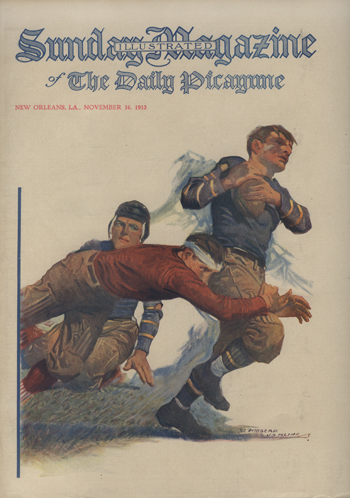

Innovator The Eliza Jane Nicholson Collection’s Sunday magazine (left, 1913). (Image courtesy of NOLA DNA)

For now, he obsesses about oversized, sepia-toned portraits of New Orleans judges encircled in typographic illustrations and crooked, flowery borders. He giggles, showing me examples of rudimentary hand-drawn borders “tipped in” atop photos. He stares down at the paper, admiring the ways in which the technologies mesh. Makkos aims to similarly mesh new digital technology with his turn-of-the-century printing presses to document and recreate aspects of the Eliza Jane Nicholson Collection. “I am a purist,” he says, “but there’s no reason not to combine every technology available.”

That includes technology that Eliza Jane would have recognized. Makkos has been interested and immersed in antiques since childhood. The son of an antique dealer in Cleveland, OH, he grew up watching his father junk, pick, salvage, and restore antique lamps and furniture. Makkos eventually developed his own vintage fetish, for antique printing presses.

In quiet, post-Katrina days, walking through the hibernating Frenchmen Street music district, Makkos would stop outside one big window covered in brown-bag paper, cut with a small, solitary-confinement-size peephole. “You could peer in and see work-desks and file cabinets, a light and a doorway, and a sign that said ‘A.F. Laborde’s Printers,’ ” he tells me. Laborde’s had operated on Frenchmen in different forms since before the turn of the 19th century. “Then everyone had just gotten up from their desks and left the Friday before Katrina,” says Makkos. “Andre Laborde dismissed all his press men, and a lot of the guys lived in the east and lost their homes, so they never came back, just took their retirements.”

Passing by the shop, Makkos often dialed the number printed on the wall outside. A year or so later, when Andre Laborde needed help clearing out, Makkos received a return call. Over the next three months, for a couple of hours every day, Makkos helped Laborde pack up and haul away tools, bars of lead, and other gritty printing ephemera. Makkos recalls shoveling small mountains of loose lead typefaces into many plastic rain buckets.

One of his friends, who worked at a now-defunct French Quarter bookstore, later gave Makkos a 9-by-13 Kelsey Excelsior press–age unknown, patented 1897–one of the largest tabletop models that company ever manufactured. “The guy’d had this press in the bookstore’s bottom-level slave quarters. They’d done one broadside run with it in the ’90s. It was rusted to shit, but I took it anyway, took it apart, took a wire brush to it and some Scotch-Brite. Spent a couple weeks on it, and now it’s fully functional.”

But his very first press, salvaged from the Bargain Center thrift, junk, and costume shop in the Bywater neighborhood, carries the most significance in terms of his newspaper project. Cast and assembled in the late 1870s or early 1880s, Makkos’ favorite iron proofing press bears the stamp of R. Hoe, who in 1847 patented the type of web press that surely printed his entire Picayune collection. Makkos’ R. Hoe is a whole different 500-pound beast: “After the type would be set by hand or else made on the linotype machine, they’d then put the type into the column-sized galley trays,” he explains. “Then they’d lay a sheet of paper down and hand ink it just to have a proof to give to the editor.”

The R. Hoe came with no letterpress type, just the rollers. It took three men to heave it upstairs to his room. Makkos rubs its gilded flower-work with pride. “I sent a photo of this to the Print History Museum in upstate New York, and they say they’ve never seen one like it,” he says. Based on his research, Makkos hypothesizes his R. Hoe came over on a ship and lived in New Orleans for more than 130 years, and was perhaps used by the union press on Chartres Street in the French Quarter, one of the first print shops in Louisiana owned and operated by its workers. Though tough to corroborate, based on his research thus far Makkos calls his R. Hoe the oldest working press in Louisiana.

Lacking wood typeset letters for his press, Makkos scoured salvage stores, searching for historic New Orleans type; he recently scored a Touro Hospital letterhead print block from the early 20th century. Makkos and an assistant have also begun sorting the buckets and drawers of galley type salvaged from Laborde’s, a task akin to completing a jigsaw puzzle of several million pieces. It has taken them a year to find and organize just two-dozen complete typefaces of sometimes-microscopic letters and numbers.

in 2012, the Times-Picayune became primarily digital, printing the paper only three days a week plus occasional supplements, and decreasing the chance that some future Makkos might one day stumble upon, say, a rare, comprehensive cache of classic Picayunes from 2013. So Makkos takes his find seriously. “We first have to digitally archive all of this more thoroughly, in a way the Times-Picayune itself either couldn’t or just never bothered to,” he says. While organizing the papers, he plans to pass them through more high-tech and, more important, larger scanners than were originally used to create the Picayune‘s current microfilm archive. He’s applied for various grants to fund this effort, and hopes to archive the entire collection before the city’s tricentennial celebration in 2018. His longer-term goal is to create a research archive and printing museum in New Orleans.

But he’s just as excited to let the collection inspire new art objects, created on his R. Hoe. Within the year, he will hand-print limited runs of historic images from his collection and create a series of books, the first exploring and documenting ways in which women are represented in Eliza Jane Nicholson’s choice of iconography. To that end, Makkos is currently at work recreating print blocks that feature illustrations from the Victorian-era newspaper. “You couldn’t reproduce it like this off of microfilm,” he says. “Having these originals is the only thing that makes this possible.” On his 1870s proofing press, Makkos will combine his new photoblocks with the old lead typefaces he shoveled out of Laborde’s, to recreate important parts of the Eliza Jane Nicholson Collection, using the same methods that created the original newspapers in the mountain of tubes and boxes that today fill his studio, and his life.

Michael Patrick Welch is a New Orleans-based journalist and author of four books. His work has appeared in Salon, McSweeney’s, The Oxford American, and Vice, among other publications. Follow him at @mpatrickwelch.