It’s not hyperbole, but I do not recall any world figure in recent years whose death evoked so many first-person reminiscences as that of Muhammad Ali.

And just think—it took The New York Times five years to allow its reporters to refer to him by his adopted name after he changed it from Cassius Clay. That change came in 1964, when he won the heavyweight title. And United Press International misspelled his name for a couple of years, before realizing he was not “Mohammad” but “Muhammad.”

In the days after his recent death, journalists were climbing over one another to get their first-person stories in the paper, and so were readers who might have seen him on a street somewhere, or asked him for an autograph, or saw him pat a little kid on the head. It was as if he had a kingly presence.

My old friend Bob Lipsyte, one of the seminal journalists in the 1960s, practically filled the Times one day with stories after Ali’s death, and Bob told me he had half a dozen radio shows he was about to do.

Muhammad Ali’s life turned into a class in journalism good and bad. At the end, I believe those who covered him had become better for it. For many journalists were forced to become tolerant, hearing another side of life from a person some of my colleagues loathed, and even feared.

The Times’s longtime columnist Arthur Daley declared Ali “a loudmouthed braggart.” And the Daily News’s Dick Young, the lead columnist for what was then America’s largest-circulation newspaper, taunted him with questions about the Black Muslims. Daley never quite came to grips with Ali’s religious conversion, even after the paper called him “Ali.” Daley, reluctantly acceding, nevertheless would refer to him as “the former” Cassius Clay. But Young eventually came to accept Ali and often wrote warmly of him toward the end of Ali’s career.

I think his life taught those of us in the business to not close our notebooks when interviewing someone with whom we disagree, and actually to engage that person in a meaningful conversation.

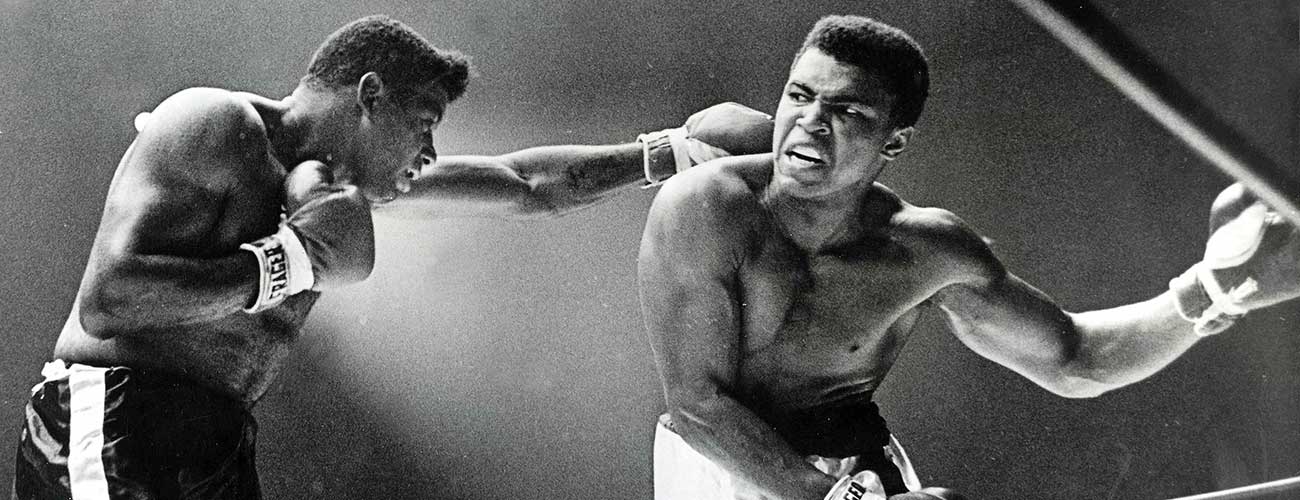

The morning after he won the heavyweight title, upsetting the fearsome and supposedly unbeatable Sonny Liston, Cassius Clay announced to the world he was Muhammad Ali, tossing what he called his “slave name.” Reporters from an earlier era, such as Young at the Daily News, refused to call him anything but Cassius. Young bemoaned what was happening to “My America” as he labeled Ali a draft-dodger.

It was a strange, mind-bending time as the Vietnam War raged. We’d be interviewing Ali, calling him “Muhammad,” but when we turned in our copy it had to be “Cassius.” Lipsyte many times tried to slip in “Ali” only to see it wind up as “Clay” in the next morning’s Times.

I was trying to understand just what Ali was all about. He had been famously quoted, after refusing to be drafted, “I ain’t got nothin’ against them Vietcong,” he told one interviewer. “None of them ever called me n*****,” he told another.* But after all, Ali was an Olympic champion, he had a group of white backers from his hometown in Louisville, Kentucky, and, quite honestly, I couldn’t understand what white America had done to get him to feel this way. Yes, I was naïve, perhaps, but I also saw him as a guy who had a lot of people rooting for him, was making a lot of money, and…well, I realize now I wasn’t walking in his shoes. I couldn’t see what the problem was. I talked to him about prejudice. He talked about empowerment.

“What did the Jews do in Miami Beach when they wouldn’t be allowed in?” he asked me. Before I could begin to think of an answer, he replied, “The Jews bought the place.” Then he looked at me and said, with an embarrassed grin, “Oops—you’re not Jewish, are you?” I told him I was, but not to worry about what he said. For when you think about it, he was right. I conceded that empowerment was necessary for blacks in America.

There were so many contradictions about him, but they helped me in my field and I’m sure they helped many other writers as well. Indeed, he and Young eventually became friends.

Ali was all over the place as champion. In 1965, a year into his reign but looking for an extra payday because the commercial world was closed to him, Ali agreed to do the color commentary of a heavyweight fight between Floyd Patterson and George Chuvalo. The promoters lined up a group of writers to visit Chuvalo’s training camp in the Catskill Mountains. We were to go by bus from Midtown.

I got on the bus and looked at the driver—it was Ali! Yes, he was going to drive the bus. It was wintertime, but we had an uneventful 90-minute ride until we came to a country road. All of a sudden the bus skidded to the side—hit an embankment and rolled over. We were tossed about, but unhurt. Someone opened the emergency door on the side and we scrambled out. I waited for Ali.

“Do you have a driver’s license?” I asked as he trudged through the snow. “Suspended,” he replied.

But on the way home, guess what? He drove the bus again. Instead of going straight back to the hotel drop-off point, though, he drove through Harlem. Suddenly, he pulled over to the curb and opened the door. A boy, about 12 years old, was standing there. Ali looked at him and waved. The boy’s mouth opened wide. Then Ali closed the door and drove off, singing, “He’s got the whole world in his hands.”

Another Ali moment of surprise and shock: After he had failed the Army’s written entrance exam, many people claimed he did it on purpose so he didn’t have to serve. It did seem inconceivable to me that this guy who made up poems about his opponents’ demise—“They all must fall/in the round I call”—couldn’t pass that dumbed-down test.

I called his old high school principal in Louisville. I asked what kind of student the voluble, fast-talking Ali had been as Cassius Clay. “Here’s something interesting,” said the principal. “His IQ was only 78.”

We then had a discussion about IQ and testing and whether it was weighted for a segment of the population to which Ali had little exposure. Perhaps. I called my wife, who ran programs for gifted children in a virtually all-black neighborhood in Queens, New York, and she suggested that it seemed impossible to her that Ali was anything less than very smart, an astute observer, and that even though he was simply one man, the whole concept of IQ as a marker of intelligence could not be valid any longer.

“No one with his insights and verbal skills could ever be considered below normal,” she explained.

But it was all part of the enigma I never completely solved in writing about him. I do know this, though: It paved the way for this journalist to forego value judgments in interviewing, to really be neutral and objective. And I have some pretty good reason to think so. For after I once asked what I thought was a perceptive question, Ali said to me, “You know, you’re not as dumb as you look.”

* This story has been changed to note Ali made these statements in separate interviews.

Gerald Eskenazi produced 8,000 bylines in more than 40 years with The New York Times , in addition to writing 16 books. He now lectures on sports and the news media.