Yes, it’s 2017. Time for a look back at that great year, 2016, and the words of the year it spawned.

The words of the year usually reflect what has happened in the past year socially and politically, and this year was no exception, overfull as it was with political and social drama. In many ways, the year seemed “surreal,” which is one reason that word ended up as Merriam-Webster’s word of the year.

M-W said “surreal” was chosen “because it was looked up significantly more frequently by users in 2016 than it was in previous years, and because there were multiple occasions on which this word was the one clearly driving people to their dictionary.” Those occasions, M-W said, were after the terror attacks in Brussels and Nice, the attempted coup in Turkey, and the biggest spike of all, after the November election in the United States.

M-W defines “surreal” as “marked by the intense irrational reality of a dream; also: unbelievable, fantastic.” All are fairly neutral in connotation; that “surreal” was used and looked up in relation to what were negative events is pretty, well, surreal.

“The dictionary is a neutral observer of the culture,” Peter Sokolowski, M-W’s editor at large, said in a video post. “We’re good at reading data. We’re not good at reading minds.”

Among M-W’s runners-up was “bigly.” Its lookups were related to the belief that Donald Trump had used it, causing mirth and derision at his not using a “real word.” But it is a real word, an adverb meaning “big.” Most people now believe Trump was saying “big league,” but swallowed half of it.

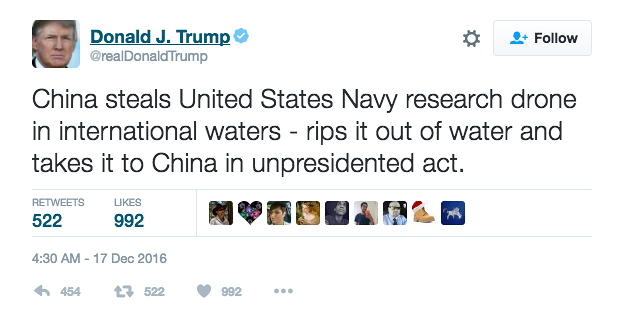

But in a tweet, a Trump misuse gave The Guardian its nomination for word of the year, “unpresidented.”

Though the tweet was deleted about 90 minutes later the (Freudian?) misspelling lives on, in hashtags, jokes, and memes, mostly aimed at Trump, whose other misspellings remain on Twitter, mostly.

Since “unpresidented” was not a real word before Dec. 17 (and is not in any reputable dictionary yet), The Guardian provided some helpful definitions: “An instance of someone being ‘prepared to say what most of us are thinking’, but actually saying things most of us are not thinking”; “An irrecoverable act of folly committed by a president”; “Feeling of loss when a president who has neither the temperament nor the knowledge to actually be president is elected president, causing one to wonder who will actually be running the country and triggering feelings of malaise and dread”; and “The state of an impeached president.”

Of course, a lot of that is tongue-in-cheek. Some of us would hope.

Not so with Dictionary.com’s word of the year, “xenophobia.”

“Some of the most prominent news stories this year have centered on fear of the ‘other’ – the Brexit vote, police shootings, Syria’s refugee crisis, transsexual rights, and the US presidential race,” the site’s blog post said. “Because these stories have resonated so deeply in the cultural consciousness over the last 12 months, Dictionary.com has chosen xenophobia as its Word of the Year.”

Dictionary.com, like Merriam-Webster, bases its words of the year on spikes in lookups. With “xenophobia,” the largest spike came after the unexpected vote in Britain to leave the European Union, and another spike after President Obama said that Trump’s rhetoric constituted “nativism or xenophobia.”

But Dictionary.com also makes its choice based on related lookups and global themes, not just in lookups of the word itself, and it cited the rise of “ideologies that promote fear or hate,” in the United States and elsewhere as part of its rationale.

Oxford Dictionaries chose “post-truth” as its word of the year, defining it as “Relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.” Oxford chooses its words of the year to “reflect the passing year in language” and said that lookups of “post-truth,” which it traces to 1992, went up by about 2,000 percent between 2015 and 2016.

Then last week, the American Dialect Society chose “dumpster fire” as its word of the year. “As a metaphor for a situation that is out of control or poorly handled, dumpster fire came into prominence in 2016, very frequently in the context of the U.S. presidential campaign,” the ADS said. (We were caught up with that as well. And yes, phrases, hashtags, and emojis can be named as words of the year.)

The ADS says it has the longest-running “words of the year” selection, and says it’s the only one not tied to commercial interest—its membership includes lexicographers, academics, writers, students, and others. “In conducting the vote, they act in fun and do not pretend to be officially inducting words into the English language,” the ADS says. “Instead, they are highlighting that language change is normal, ongoing, and entertaining.”

For many, though, the “dumpster fire” that was 2016 was not “normal” or “entertaining.” But it was certainly “surreal.”

Merrill Perlman managed copy desks across the newsroom at the New York Times, where she worked for twenty-five years. Follow her on Twitter at @meperl.