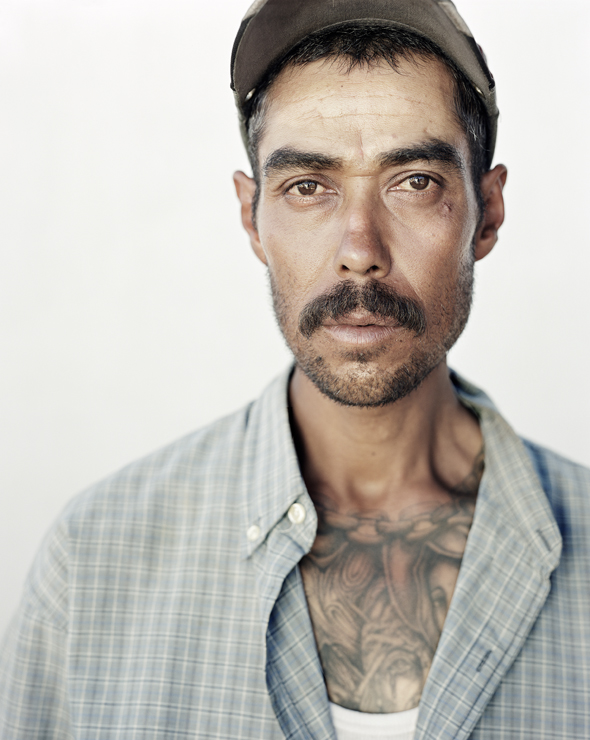

Undocumented José had worked in kitchens in the US before being apprehended by authorities. (David Harriman)

Every year, the United States deports hundreds of thousands of undocumented immigrants back to Mexico. Since 2008, David Harriman has been at the border photographing people just after they reenter the country.

Harriman, a British photographer based in London, takes portraits of returning migrants for “Mariposa” (“Butterfly” in Spanish), an ongoing project documenting Mexican repatriation. Over the past few years, Harriman, 48, has periodically flown to the American Southwest to shoot portraits; there are currently more than 100 in the collection.

“When these people are repatriated, the furthest thing from their mind is getting photographed,” Harriman says. “But having said that, they were really happy to engage once I got into it.”

During each trip, he stays in Tucson, AZ, and every morning, he drives about 70 miles south to Nogales, Mexico, just over the border. With an assistant, a large-format camera, and diffusion panels, Harriman sets up a makeshift studio on a patch of of scrubland, or near a small bus station. Sometimes, he says, he’ll wait at the crossing for hours without seeing anyone go by. Other times, buses with more than 100 people enter the country.

The idea stemmed from one of Harriman’s earlier projects, “La Linea” (“The Line”), an effort to document the landscape of the US-Mexico border. “I thought, I couldn’t not document the people, the humanity involved with it,” he says. He hopes to turn the project into a book.

Harriman’s lifelong fascination with American landscapes and culture first drew him to the subject. “I became fascinated that the usa just kind of runs out, and then a very different culture begins,” Harriman says. That is, the US has long expanses of uninhabited terrain between metropolitan areas, an openness the UK lacks. “That drives my eye, more than if I’m back in my own homeland.”

“Mariposa” is named for the Mariposa crossing at Nogales, a place where Harriman has met all sorts of people, from those who had attempted to cross the border just hours before being deported to those who had been living in the US for years.

On one shoot, Harriman met a family with two children that had lived in the US for three years before being sent back to Mexico. The only possession they had was a blanket. On another, a woman approached Harriman, frantically claiming that a coyote, a person who smuggles migrants across the border, had assaulted her. “I didn’t actually want to photograph her, but she insisted that I did, so it was a difficult one,” Harriman says. In broken Spanish he asked her to be still for the camera, and as she became calm, tears began to roll down her cheeks.

While the border itself has changed dramatically over the past decade–high fences have replaced old barbed wire in many places–Harriman has kept his portrait style consistent. “In order to document something over such periods of time, you’ve got to have some consistency, so every time I’d go down there I’d be trying to see it through the same eyes,” he says.

Harriman says the “Mariposa” project falls somewhere between journalism and fine art. It’s not photojournalism in the purest sense–it’s more intentional, and more formal–but his work serves a journalistic purpose. “I think anything where you’re telling a story crosses over into photojournalism,” Harriman says. The stories he’s telling are about the plight of people who want to escape the lives they were born into. “It’s all about hope,” he says, “but their hope’s just run out at that point.”

Nicola Pring is a CJR intern