Book reviewers for newspapers write the first draft of cultural history. Or so we tell ourselves, at times, to lift our spirits. Of late this is not so easy. All signs now point to a future in which the news hole for cultural coverage will be budgeted strictly for updates on celebrity pregnancies. Authors are going to keep on writing books, of course, but exposure will involve coordinating the efforts of a publicist and a fertility expert.

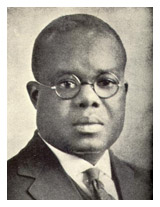

To some of us, it seems obvious that newspapers should respect, and even foster, the activity of reading as such—obvious and yet, given the circumstances, also mildly subversive. So perhaps it is a fitting time to rediscover Hubert Harrison (1883-1927), a left-wing “community organizer,” as we say nowadays, who once jokingly proclaimed himself “the only ‘certified’ Negro book-reviewer in captivity.”

To some of us, it seems obvious that newspapers should respect, and even foster, the activity of reading as such—obvious and yet, given the circumstances, also mildly subversive. So perhaps it is a fitting time to rediscover Hubert Harrison (1883-1927), a left-wing “community organizer,” as we say nowadays, who once jokingly proclaimed himself “the only ‘certified’ Negro book-reviewer in captivity.”

His public debut came in 1907 with a letter to The New York Times complaining about its books coverage—arguably rendering him a literary blogger avant la lettre. By the early 1920s, Harrison edited what he called “the first regular book-review section known to Negro newspaperdom.” He had passed through the ranks of the Socialist Party and Marcus Garvey’s early black nationalist organization, and his commentary on books naturally tended to have a polemical edge. But his sense of mission went beyond using reviews as a format for social criticism. He also saw reviewing as a way to consolidate an audience that took pride in its own seriousness about reading.

Prominent in his own day, Harrison was all but completely forgotten until his excavation by Jeffrey B. Perry, a retired postal worker, whose Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918 was published in December by Columbia University Press. For a brief look at Harrison’s life and accomplishments, let me point the reader to my piece on the book, and also mention this sketch of how Perry came to excavate his hero’s literary remains.

Out of some 700 items by Harrison in magazines and newspapers, roughly ten percent were book reviews. He also wrote a handful of incisive commentaries on African-American theater of the 1910s and 1920s, including an assessment of The Emperor Jones that Eugene O’Neill considered among the most insightful. A selection of his book and theater reviews appears in Perry’s volume A Hubert Harrison Reader (Wesleyan University Press, 2001). Even better news: the entire run of his journalistic output will be made available through a digital archive hosted by the Columbia University library system.

For bedraggled cultural journalists in our own century, it is inspiring to see Harrison’s sense of the dignity and needfulness of what we do. Book reviewers are, he insisted, “literary critics in their working clothes.” In a 1907 New York Times article, Harrison divided their labors into four broad categories: impressionism (which sounds like a breezy feuilleton), comparative criticism, interpretation, and creative criticism. One senses that the latter type of work was closest to Harrison’s heart. It was “the highest of all,” he wrote, an endeavor “which—to crib an expression from Matthew Arnold—creates new currents of thought to act as points of departure.”

By Harrison’s lights, a critic handling new books could work in any of these modes, even the most demanding. Still, he complained that reviewers for the Times were often lazy and hazy about their job. Writing some fifteen years later, he offered the advice of a literary veteran to “new recruits” joining the critical ranks. It would be hard to improve on his recommendations.

“In the first place,” he wrote, “remember that in a book review you are writing for a public who want to know whether it is worth their while to read the book about which you are writing. They are primarily interested more in what the author set himself to do and how he does it than in your own private loves and hates. Not that these are without value, but they are strictly secondary. In the next place, respect yourself and your office so much that you will not complacently pass and praise drivel and rubbish. Grant that you don’t know everything; you still must steer true to the lights of your knowledge. Give honest service; only so will your opinion come to have weight with your readers. Remember, too, that you can not well review a work on African history, for instance, if that is the only work on the subject that you have read. Therefore, read widely and be well informed. Get the widest basis of knowledge for your judgment; then back your judgment to the limit.”

Harrison’s own “base of knowledge” was encyclopedic. Besides reading Latin, he kept up with books in several European languages, and at one point he intended to study Arabic. But the very ardor of his devotion to critical journalism made it harder to bear the scorn of white book publishers, who tended not to send review copies to black newspapers even after repeated requests. This policy, wrote Harrison in one column, “is short-sighted and unsound. After all, pennies are pennies, and books are published to be sold. We believe that the Negro reading public will buy books—when they know of their existence.”

His work for newspapers was just one part of Harrison’s rich and complicated career as a public intellectual. Among other things, he seems to have been a speaker so effective as to make Cornel West seem tongue-tied by comparison. But some index of how badly he faded from the historical record can be found in Oxford University Press’s new Encyclopedia of African-American History, 1896 to the Present. Its five massive volumes make a few passing references to Harrison, but he has no entry of his own.

While Jeffrey Perry has rescued Hubert Harrison for the historians, perhaps it is book reviewers who should erect a memorial to him. For he was one of our own. His devotion to a thankless task should make him our patron saint—unless, of course, we give that over to St. Jude, who traditionally handles lost or desperate causes.

Scott McLemee is on the board of the National Book Critics Circle. In 2004, he received its Nona Balakian Citation for Excellence in Reviewing.