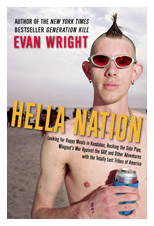

Evan Wright won himself a mass audience with Generation Kill (2004), which expanded on the Iraqi reportage he had done for Rolling Stone. The subsequent TV series made from the book has ensured that his name is identified with gonzo-flavored war reporting. Yet this Dispatches-on-the-Euphrates vibe does an injustice to the range of Wright’s work, which has more recently appeared in Vanity Fair and the Los Angeles Times. He has written about skateboarders and anarchists, skinheads and porn merchants—a disparate group united mainly by their outsider status. Notwithstanding its hyperventilating subtitle, Hella Nation: Looking for Happy Meals in Kandahar, Rocking the Side Pipe, Wingnut’s War Against the GAP, and Other Adventures with the Totally Lost Tribes of America collects the best of these pieces. In a conversation with CJR’s James Marcus, the author splits hairs over how best to define what he calls “rejectionists,” and denies his debt to the late Hunter S. Thompson—sort of.

Let me begin with a question about the earliest piece here, “Heil Hitler, America,” which appeared in Hustler in 1997. As you note in your introduction, Max Frankel of The New York Times singled it out as a squalid fiction, not to mention a recruiting poster for neo-Nazi thuggery.

Let me begin with a question about the earliest piece here, “Heil Hitler, America,” which appeared in Hustler in 1997. As you note in your introduction, Max Frankel of The New York Times singled it out as a squalid fiction, not to mention a recruiting poster for neo-Nazi thuggery.

I should say that you’re a little late. I wrote to the Columbia Journalism Review back in 1997, after Max Frankel wrote this editorial saying that I had made the whole thing up. I demanded my day in court at CJR.

Did they write back?

No. That’s how insignificant I was.

How about the Aryan Nations crowd you profiled in the piece—did you get any fan mail from them?

No, I didn’t, which is more surprising. No reaction whatsoever.

And how about your other subjects in Hella Nation? How have they responded to your portraits of them?

The pieces are so different that the responses have been different as well. The military people—the guys in the 101st Airborne in Kandahar—really liked what I wrote. In fact, when I was in Baghdad in 2007, working on a different story, I was in this bad neighborhood, and this guy came running after me! He had been profiled in the 2002 piece, and he said, “Man, that was great, I never got to thank you.” That was one of the funniest responses.

The weirdest thing was that mad-dogs-and-lawyers story, which resulted in a death threat. It was taken very seriously by law enforcement in California: they gave me various warnings, and I met with the prosecutor in San Francisco. It was very strange.

You’ve often been compared to Hunter S. Thompson, a line of descent you dispute on the very first page of the book. You suggest that his brand of gonzo journalism is often “more about the reporter than the subject.” If that’s the case, who do you view as your predecessors, both in terms of style and subject?

That’s a hard question. A.J. Liebling—now, his style is a little different, but his subject matter was the largely the same. He wrote about underworld characters: dancers, boxers, and so forth.

Is that how you would characterize your own subjects?

Yes. It’s not always that they are underworld, but that they’re perceived that way. But you know, Hunter Thompson actually is one of my biggest influences. What I’ve always disliked, especially after they made the Johnny Depp movie, was the way he was turned into a character.

So you’re talking about his earlier work, where his own personality didn’t loom quite so large.

I’m talking about Hell’s Angels, which is just great immersion reporting, and even some of the later stuff. In Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72, he writes this crazy Hunter Thompson thing in the introduction, about how he had to carry all his guns to Washington to do his political reporting. But then you start reading the book, and it’s actually by this guy who’s obsessed with the inner game of politics and knows all the players.

Let me backtrack and say something else. In the publisher’s rush to market (which I thoroughly applaud), they tend to spin things: oh, he writes about subcultures. Or: the underworld. What I’m really interested in is people who are voiceless. And voiceless doesn’t necessarily mean somebody who’s powerless, cowering in the corner, afraid to speak. It’s people who we’ve seen again and again in televised media, and yet we have no idea what they actually think or say.

Would the WTO anarchists in “Wingnut’s Last Day on Earth” be one example of that?

Right. For a week the international media saturation-bombed us with images of these kids in black smashing windows, but nobody was really talking to them. Same thing when I went to cover the military. There was all this footage of our troops as heroes, and of course most reporters tend to talk to the officers—because reporters go to college, and officers go to college. So I decided to write about it from the standpoint of enlisted personnel.

What else draws you to these voiceless subjects, whom you call “rejectionists” in your introduction?

Well, here’s a little personal narrative that I didn’t put into the introduction. In a nutshell: when I was thirteen, I was insanely obsessed with Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul On Ice. This was in rural Ohio, where I wanted to lead a Black Panther revolution. I ran away, and was sent to a home for troubled kids. That all resolved itself, years ago, but I still have a real affection for people struggling with some ridiculous obsession. I want to be a voice for the voiceless—you know, that noble thing—but I also have a personal affinity for rejectionists.

One great strength of the book is that you can write about Wingnut and his comical cadre without making fun of them.

I’m glad that comes across. I’m trying to reject the whole hipster irony culture. You know the idea: you leave New York or Los Angeles (two places where I’ve spent most of my adult life), and then you find idiots in the hinterlands, and show what buffoons they are. I suppose that because I actually am from the hinterlands, I dislike that kind of journalism.

I’m glad that comes across. I’m trying to reject the whole hipster irony culture. You know the idea: you leave New York or Los Angeles (two places where I’ve spent most of my adult life), and then you find idiots in the hinterlands, and show what buffoons they are. I suppose that because I actually am from the hinterlands, I dislike that kind of journalism.

In any case, it exists more on television. The saddest part about being a print person is that we’re saddled with all of the sins of TV. I mean, I’m out in the world working as a journalist, and people tell me, “I hate the mainstream media!” I have to correct them: no, you hate television. They’re the ones who do the worst things. We’ve got Judith Miller from The New York Times, but we’re not nearly as bad as TV.

In “Scenes from My Life in Porn,” you note that “porn video is indigenous Southern California folk art. The cheesy aesthetic—shag-carpet backdrops, tanning-salon chic, bad music, worse hairdos—and the everyman approach to exhibitionism are honest expressions of life in the land of mini-malls, vanity plates and instant stardom.” To what extent do you mean your portraits of America’s “lost tribes” to tell us something about the bigger culture?

I want to throw it out there, the possibility of commenting on the bigger culture, but I’d rather the readers draw their own conclusions. One of my pet peeves is that I dislike journalism that tells us what to think about the big picture. I should also say that I was paraphrasing (not plagiarizing!) a line of P.J. O’Rourke’s there. He once said that serial killers were a form of American folk art. It’s a little homage.

Later in the same piece, you describe your stunned state of mind on the set of The World’s Biggest Gang Bang II. You were, as you write, in the midst of “a group of people deliberately and methodically engaged in acts of insanity.” That sentence might apply to more than one of your pieces, don’t you think?

Yes. And the other thing is, in that same passage, I compare it to descriptions of combat, which is funny, because years later, I ended up in combat many times. And when I was in combat, it was not that surprising to me, because I had already experienced The World’s Biggest Gang Bang II.

This could be an innovative new training regimen for the military.

I think some of them have already taken that course. But anyway, I do think that many human activities can be filed under that description. Again, I always refer back to television. The televised media shows certain images over and over, and that gives them such power that they almost have the force of logic.

Take the anarchists: you have the dominant image of the WTO, the black-clad kids smashing windows. The images convey an entire, unspoken narrative: these are angry protestors smashing windows because they’re outraged, they’re full of righteous anger. As a print person, I feel that it’s my job to go back and see what was really happening. And what I find is that it’s often a bunch of people doing things for no reason whatsoever. In fact, the anarchists weren’t angry when they were smashing windows, they were having fun. And they weren’t really righteous, they were followers of a real wacko named John Zerzan. A lot of my journalism is focused on revealing the absurdism behind so many of our actions. It’s not a deliberate mission, it just sort of happens.

You peek into some dark and dangerous corners in Hella Nation. Yet often you encounter these strange, contradictory pockets of innocence. The buff soldiers of the Fifth Platoon Delta Company “still give the impression of hometown innocence,” and even the taxi-dance halls you chronicle in Los Angeles have a kind of dowdy sweetness to them. Is that always there?

Once you remove your own preconceptions as a journalist, you often find that sort of innocence—often in people who are doing very destructive things. That makes it more confounding. It really proves that innocence itself is not necessarily a wholesome thing.

About Generation Kill, you said: “I’m apolitical, but I do hope it pisses off more people on the left than on the right.” Is this book designed to piss off that same demographic?

That quote was more in reference to the politics of the war. I’m not sure what motivated me to say it [laughs]. But I think is has something to do with how the troops are perceived—that’s what I was talking about. The left has gone overboard trying to portray them as victims of bad recruiters. My point was that a lot of the troops actually like fighting and going back to Iraq. As for this book, I actually have no sense of who it would anger at all.

Maybe you’ll get lucky and piss off the entire population.

When you publish a book these days, the easiest way to sell it is to put something really incendiary on the cover. Publishers want strong political opinions, strong cultural opinions. But unfortunately for the sales department, I don’t offer that.

James Marcus is the deputy editor of Harper’s Magazine. His next book, Glad to the Brink of Fear: A Portrait of Emerson in Eighteen Installments, will be published in 2015.