Last September I went on assignment with a translator to Dagestan, a Russian republic on the Caspian Sea. Since we were reporting on the Islamic insurgency, which has been simmering there since the 1990s, it wasn’t particularly encouraging when our taxi was stormed by four huge men in blue camouflage who pointed assault rifles and shouted threats. It further dawned on me that the situation had become problematic when the operatives pushed us out of the car and marched us at gunpoint into the dreaded “Department Six” anti-terrorism headquarters. The penny finally dropped when I saw the sign above the door of the interrogation room. It read, “For the Wanted.” Just then, a particularly aggressive man barked that we would never get out.

“Um, not good,” the translator whispered.

We had both known that detention was a risk on this trip, as she had been arrested a couple of times before. Frankly, I should have known better, because I teach conflict-zone reporting and spend hours telling other people how to avoid such perils. We had foolishly ignored Rule No. 1: Don’t stumble into a danger trap. I’m normally a cautious wimp, and had been careful earlier in the week about whom to approach. We hired drivers who remained ignorant about our mission. We never sent sensitive e-mails.

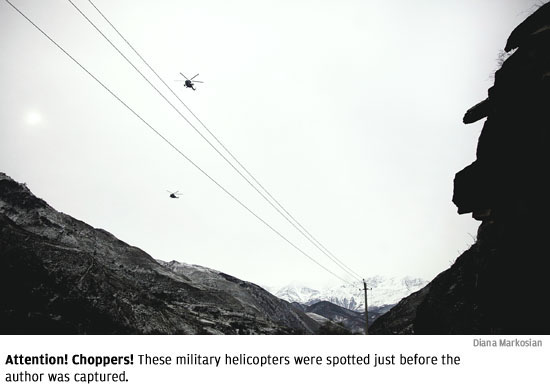

But we got sloppy on this afternoon, when we impulsively poked around the town of Khasayurt, a goryachaya tochka, or hot spot, where security forces were rounding up suspected terrorists and shooting them. We should have alerted the former deputy mayor, with whom we dined the previous night, to arrange an official escort. We should have turned around when military helicopters whirled overhead. But we didn’t.

Unbeknownst, we had blundered into a “special operation” against the Islamic extremists who want to establish an independent Muslim state in Russia’s North Caucasus region. The stunning mountainous area is a growing stage for an international jihad, and bombs and shootings occurred daily the week we were there. Authorities deem the rebellion the biggest security threat in Russia, and they don’t look fondly upon independent journalists who witness their harsh responses.

All this was flitting through my head as the snarling man told us what he thought about human rights—not much—and waved his AK-47. Meanwhile, two secret service agents inspected our documents. Rule No. 2 is to have a contingency plan and we did, thank God. We regularly checked in with our editors, so they would notice if we didn’t call that evening. Our wills were in order. We coded incriminating information and were carrying clean notebooks with the names of Very Important People. Our credentials looked fine. We had emergency contacts on speed dial. Back at the hotel I had piled dirty laundry on top of my computer. If agents bothered to face the mess, all they would find was a dummy laptop that I used for traveling. It had innocuous files and a clean browser history and no suspicious software. Our cover story was bland and true: I was researching a book about mountains and conflict.

However, the fact that Khasayurt was far from the hills troubled our interrogators, as did the fact that we had made contact with a woman whose son their buddies had assassinated. I tried to divert their attention by pointing out we had committed no crime. (Rule No. 3: Know the law and don’t break it.) To which the barking man replied: “Our notion of democracy is different from yours.” He touched his gun for extra effect.

The two secret agents, meanwhile, played a classic “good cop, bad cop” routine, complete with offering cigarettes (bad cop) and health warnings (the good one). “Take it,” the mean cop snarled, pushing the tempting smokes toward me. “Don’t! Smoking is unhealthy,” urged the nice one. Spotting an opening, the translator beckoned the good cop into the hall. (Rule No. 4: Gain control of the situation.) She informed him that I was an extremely famous person whose capture would cause a diplomatic mess. “You wouldn’t want that,” she counseled, to which he replied, “Oh, no.” Upon returning to the cell he dismissed the barking policeman with an apologetic, “These guys are unprofessional.”

Now we had to ensure the translator’s well being. Her Russian passport put her in danger, as local journalists can be knocked off in this region. As an American, I faced some risk of maltreatment, but generally authorities simply expel pesky foreigners rather than kill them. The translator was probably okay as long as we remained together, and for that we played the female card. “I promised her mother I would take care of the girl,” I said, throwing a protective arm around her shoulders. “She stays by my side.”

The translator in turn scolded the men: “She’s old enough to be your mother.” I winced slightly at this. “Would you treat your mother like this?”

They agreed they would not.

Here I summed up Rule… well, it doesn’t have a number, but sometimes there’s no recourse but to Bore Your Captors Out of Their Skulls. “Look,” I said, leaning forward as the bad cop lit me a cigarette, “I have this theory about mountain clans. They’re always fighting.”

“Definitely in Dagestan!” said the pleasant cop. “We have 40 warring clans. You must visit the mountains.”

“If we let her out,” snarled the wicked one.

I tried to distract him with a ramble about the traits of highland folk, starting with tribes in Papua New Guinea. “Mountain people have a different mentality. They’re suspicious of outsiders”—I shot him a look here. “Why are Dutchmen peaceful? Because it’s a flat country and they have to get along, but when you gain altitude people start sparring, because you can’t see what’s on the other side of the hill, and generally lowlanders subjugate people living at high altitude and exploit their natural resources. Think about it,” I went on. “We see this all over the world, in Kashmir, Appalachia, Ecuador, the Atlas Mountains, even the Pyrenees. Some 80 percent of conflict occurs in…. ”

“Enough!” shouted the bad cop. “You’re giving me a headache. Let’s drink tea.”

The duo escorted us upstairs to a toasty room, where we sank into a plush sofa in front of a flat-screen television. There, a woman on a talk show sobbed about her dead son. I guessed his demise was linked to the insurgency when the mean agent snarled, “So this is what you came here to see?” The nice guy broke out a package of cookies and put water on to boil. “I recommend the raspberry variant,” he said, adding that he would drink from the same pot to prove it was not poisoned. (Rule 5: Be wary of drugged refreshments.)

After a few ladylike sips, the translator asked for the bathroom, where she checked off Rule 6: Text emergency contacts. (We had held onto our cell phones after the interpreter swatted the gunmen’s hand, on the grounds that good Muslim men don’t touch strange women.) I followed suit with an e-mail to my husband about our whereabouts, so that he could inform diplomats in Moscow. (Rule 7: Make sure spouse has embassy number.)

Over tea, we interviewed the chaps about their covert jobs. Rule… well, there’s no number for this one either, but Flatter Your Captors As If Your Life Depends On It. This can work, too. After dispensing with pleasantries about their intelligence, our journalistic curiosity got the better of us and we grilled the pair about life in the Federal Security Services. It’s a rare reporter who gets the inside scoop on Russian spies, and the lads welcomed a sympathetic ear. “We receive no overtime pay and toil every weekend,” griped the nice one. He hungrily reached for another biscuit.

“You can’t imagine some of the people we arrest,” said the malicious one. He shot an appreciative glance at the interpreter. “It’s a pleasure detaining a pretty woman.”

Conversation hit a lull and the interpreter suggested that they release us in time for dinner. They agreed. It was as simple as that. Everyone said goodbye with handshakes, and warnings about menacing terrorists. Then they gave us their telephones numbers. The kind one even walked us to the car.

“How about a drink if I knock off work early?” he asked hopefully.

The translator politely demurred. Rule No. 8: Don’t date sources, especially sources with guns.

Judith Matloff teaches conflict reporting at Columbia's Graduate School of Journalism. She's the author of two books on conflict, Fragments of a Forgotten War and No Friends But the Mountains, as well as a manual for journalists covering dangerous stories, How to Drag a Body.