On my first day at the Columbia Journalism Review, the editors were reading page proofs for an upcoming issue, and if you found a glitch, the editor who had read the piece before you had to pitch a coin into a pizza-fund jar—a dime to a quarter, depending on the grievousness of the error. This provided a quick insight into the economics of the place. Also, it was fun. I thought, maybe I could work here for a while.

So, I did. The copy we were reading that fall day was for the twenty-fifth anniversary issue, and here we are—zip!—at the fiftieth, trying to peer into the past and the future, as I will here. I see that Jim Boylan, CJR’s founding editor, stole all the Pulitzer quotes for his essay on the previous pages. So if you don’t mind, I’ll start this on a personal note and save the mission material for the end.

I came to CJR as half of a junior editor, splitting the position with my wife, Mary Ellen Schoonmaker, as we had done before on the copy desk at BusinessWeek. We took bimonthly turns, one of us working at the magazine while the other tended toddlers and wrote freelance. In one of my at-home stints, I wrote a long piece for CJR. Mary Ellen delivered the manuscript, and her desk was positioned in a way that allowed her to observe the reaction of the editor, a thin and classy man named Spencer Klaw. “He danced,” she whispered to me on the phone. “What?” I said. “He danced,” she said, “in the hall.” Thus was the hook set.

Klaw, who died in 2004, edited the magazine from 1980 to 1989. If I was ever going to be an editor, I thought in those days, here was the model. He didn’t scare anybody; you just didn’t want to disappoint him. His lieutenants were a bear of a man named Jon Swan, who spun straw prose into gold overnight, like Rumplestiltskin, and the steely Gloria Cooper, passionate and smart. Some time before I started, the legend goes, Gloria detected inadequate valuation of her work, vis-a-vis Jon’s work, and secretly wrote an unsigned commentary, overnight, on Jon’s typewriter. When Spencer praised the puzzled Jon the following morning, Gloria was all cat and canary.

This is a good moment to thank all of them for caring for the flame that Jim Boylan and his colleagues lit back in 1961, and to thank all the editors and staff members before and after them. In my time, Suzanne Levine was the editor after Spencer, and led the magazine in a fairly gutsy fashion between 1989 and 1997. In 1994, she sent Trudy Lieberman to write about David Bossie, the activist who at the time was feeding Whitewater gumbo to reporters. We could not obtain a photo, so Suzanne hired a police artist, who revised and revised his sketch until Trudy said, bingo!—that’s the guy. Marshall Loeb came next, from 1997 to 1999, and pushed the magazine in a slicker direction that reflected his roots at Fortune and Money. I have a memory of Marshall walking into the office early one morning with two immense suitcases, after what must have been a grueling all-night flight from China. He was in his seventies by then, but he dove into the pile of papers on his desk with what looked to me like rapture.

It is David Laventhol whom I would personally like to thank most of all. David was named CJR’s publisher in 1999, and shortly after that its chairman and editorial director. This was after a career in which he had re-shaped a great swath of the newspaper landscape, in an era in which the big dailies were aiming for the stars. He more or less invented the Style section at The Washington Post, helped build Newsday into a powerhouse as its editor and then its publisher; he served as publisher at the Los Angeles Times and then as president of Times Mirror. He liked to stretch journalistic ambitions and boundaries and understood that CJR was born to agitate for exactly that agenda. In 2000, he installed me as executive editor and Brent Cunningham as managing editor—pilot and co-pilot—and kindly eased us into the roles as he eased his way toward retirement.

David and I more or less took turns doing issues for a while, and one of my early ones was a big package on newsroom morale, complete with a survey and pretty cool cover art. I was proud for about a week. It arrived in people’s mailboxes around September 11, 2001, after which nobody ever thought much about newsroom morale again.

Until shortly before we put together this fiftieth anniversary issue, I had not stopped to realize that I’ve been running the editorial side of CJR for a decade. Which is nice. It’s never been a particularly safe position, given that dreams of solvency and greater impact regularly elicit new beginnings, and given that our audience tends to include a set of journalists who assume they could do a better job with it, an indeterminate subset of which may be right. So I feel lucky. To quote Dr. Seuss, These things are fun, and fun is good.

I mean the working kind of fun. We redesigned the magazine twice in that period. We published a book, Reporting Iraq, to be proud of. We won some shiny prizes. We became a better citizen of the world, looking more often beyond the borders of the United States. We wrestled hard, sometimes well, with the technical, economic, and cultural shock waves that have so deeply shaken journalism in this period. It has been, you may have noticed, some kind of decade.

In 2004, we built and staffed a website to cover the coverage of presidential politics, later merging that into CJR.org to create a handsome six-desk press criticism-and-analysis machine. There we cover the coverage of politics and policy, in a time of ferocious and context-free debate (Campaign Desk); business and finance, during a killer recession (The Audit); science and the environment, at a moment when a serious presidential candidate can deny evolution (The Observatory); news innovation and economics, in the middle of a wild and unpredictable interregnum for the business (The News Frontier, and The News Frontier Database); media issues and occurrences (Behind the News); and journalism-related books and culture (Page Views). A sharp crew of writers, thoughtful and fast, works under the steady hand of Justin Peters and, in the case of The Audit, Dean Starkman. There was a period when web and print did not harmonize here, when there were budget wars and a wall—metaphoric and literal—between CJR print and CJR digital. We took it down. The young staff, digital to their bones, is eager to write for the fifty-year-old print magazine, too, which makes me happy.

In print, I look back at the early part of the decade and wish we had some of those cover stories back. With a bimonthly you only get six at-bats a year, and you want a home run every time. Two that we did hit over the wall in those years are Brent Cunningham’s “Re-thinking Objectivity” in July 2003 and Liz Cox Barrett’s “Imagine” from that January, in which she set up several brainstorming parties of young newspaper reporters all over America and constructed a vision of a dream daily out of their collective mind.

I do think our on-base percentage rose steadily through the years. I am proud of just about all of the Second Read features we have published in the back of the book, in which writers recall a book that helped shape them, or that should not be forgotten. I am particularly proud of “Into the Abyss,” our cover piece in November 2006, which presented the voices of the journalists covering Iraq at its worst, in oral-history fashion, and which would become Reporting Iraq; of Michael Shapiro’s portrait of The Philadelphia Inquirer in agony, in the March issue that year; and of Eric Umansky’s treatise on the coverage of torture, in the September issue. In 2008, I thought Lawrence Lanahan’s layering of The Wire against urban journalism in real-life Baltimore, from January 2008, was a revelation, and so was Bree Nordenson’s exploration of the ramifications of information overload, in November. In 2009, we looked at the future of journalism in three separate cover packages, from three perspectives, and won a lovely crystal media-criticism trophy from Penn State for our efforts, which is sparkling above my desk as I write.

That year also brought Dean Starkman’s May cover piece on the failure of the business press in the run-up to the financial meltdown, the kind of press criticism this magazine was born to produce. (It will be expanded into a CJR book, The Watchdog That Didn’t Bark, next year, with our new books partner, Columbia University Press.) Starkman had another winner in 2010, with his “Hamster Wheel” piece on the great newsroom speedup and its journalistic costs. Moe Tkacik’s “Look at Me!”, a barbed critique of journalism in the age of branding, was loved or hated by all who read it. I loved it. And I have loved most of our cover pieces this year, and much of the rest of what has been in between the covers. What can I tell you?

If this is starting to sound nostalgic, it is somewhat nostalgic. I am not going anywhere and, God willing, will continue as CJR’s executive editor for a good run. What is new is that thanks to a generous funder, CJR is in the process of hiring an editor in chief, to whom I will report, and with whom I hope to launch this place into the next half century. Among other things the editor in chief will be, I am told, is someone who enjoys giving speeches and being on panels about the future more than I do (which is not so much). That editor will find there is plenty of work to share.

As an orientation exercise, perhaps the new editor and I will listen together to my greatest-hits phone-message collection. I have saved one from the late David Halberstam, for example. Imagine a voice that sounds exactly like God, telling you emphatically he is not used to people messing with his copy. Another is from Richard Johnson, who once wrote an oily gossip column for the New York Post. The message begins: “I am doing a story about how the Columbia Journalism Review has embarrassed itself . . .” (Actually, we had done no such thing.) On the other side of the ledger is an e-mail from a political science major named Julian from Canada who said he had come across CJR in the bookstore where he works. What Julian wanted to know is this: “It seems you guys are not a huge magazine, and thus I’ve been buying every issue when I see it at work (as an employee I could just borrow it for free) in order to help support you guys. I was just wondering, would I be more helpful to your continued survival as a publication if I subscribed?” God bless you, Julian. If you need an internship, just call.

One message that I erased, unfortunately, came from Seymour Hersh, but I remember it vividly and can supply a dramatic re-enactment: Scott Sherman, a longtime contributing editor to CJR, was reporting his terrific 2003 profile of the great investigative reporter. A dispute erupted about whether a nice anecdote that Scott had witnessed was on the record, or off. The phone message went this way: “Hoyt? Hersh. Who the fuck is Scott Sherman and what the fuck is he doing? What he’s doing is wrong. It’s wrong!” This was followed by the sound of a phone slamming down. Everyone survived, including Scott, and I want to thank Seymour Hersh for his kind letter to CJR at fifty, which you can read on page 19, as well as for his years of indispensable investigations.

While I am expressing gratitude, I want to thank Victor Navasky, CJR’s wise and resourceful chairman, who has done nothing less than keep this place in the black and glued together, with the help of the stalwart Dennis Giza, CJR’s fiscal compass, and our co-chairman, Peter Osnos. I want to also thank our dean, Nicholas Lemann, who has given CJR nothing but support and good ideas, and absorbed more arrows on our behalf than we’ll ever know.

And then there is the staff. One editorial skill I am quite confident I have is the ability to hire strong and creative people, because, hey, look at them. I cannot say enough about these hardworking, wicked-smart, and articulate writers and editors. And thanks to all those great free-lance writers through all those years, too—except the ones who were late.

Finally, you, the reader, without whom, who cares? All of us connected to CJR—staff and readers, friends and enemies—seem to know that we are part of a conversation that matters. Journalism matters. This is something we know even more deeply now that it seems to be a resource we can no longer take for granted, like the air.

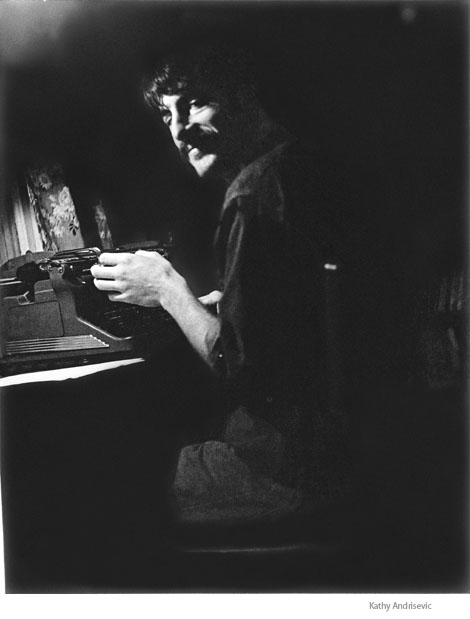

Two weeks before I went to journalism school, back in Missouri and back in the day, it dawned on me that reporters probably had to type. So I bought a used textbook, covered the keys with little red stickers as the book suggested, and learned how. You can see the typewriter, my father’s Underwood, in the accompanying photo of the guy with the moustache and no clue of what lies ahead.

The real lesson came much later, after years on the job: that journalism is not all that difficult, really, but journalism of value is difficult indeed. CJR is that voice saying it is worth the effort. I cannot express the goal we share here better than Jim Boylan did fifty years ago in CJR’s founding editorial, which you can read here—in that line about the need for journalism that is a match for the complications of the age.

Our age is most complicated. It requires a level of journalism to match it. CJR can help with that. Let’s go.

Mike Hoyt was CJR’s executive editor from 2001 to 2013, teaches at Columbia’s Journalism School and is the editor of The Big Roundtable, a startup that is a home for narrative writing.