Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt is the result, a messy albeit well-intentioned hybrid of reportage, oral history, and polemic. Hedges, who won a Pulitzer with The New York Times, and Sacco, an artist-journalist whose book Palestine won the American Book Award, have both been praised for their conflict coverage, and Days of Destruction bluntly depicts its subjects as casualties of war—a war waged by the malign forces of corporate capitalism against the hapless chumps who work for a living. It is an effective jeremiad that falls short as documentary, with solid reporting undermined by clunky agitprop that ultimately detracts from the book’s message.

Since leaving the Times in 2003, Hedges has reminded me of an Amish boy on rumspringa, rejecting his alma mater’s down-the-middle dispassion in favor of a stridently progressive, heart-on-sleeve approach to journalism. Days continues in this vein, and, to his credit, Hedges is quite clear that he and Sacco are acting not as neutral observers, but as men on a mission. Their goal: “To show…what life looks like when the marketplace rules without constraints, where human beings and the natural world are used and then discarded to maximize profit.”

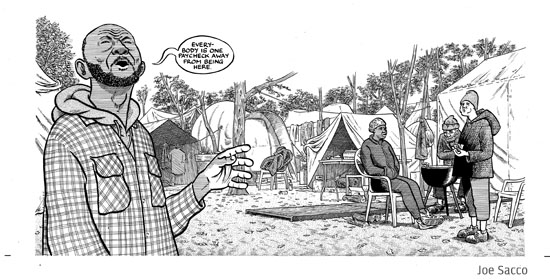

They do this by depicting four American crisis zones in long chapters that alternate between text, in which Hedges describes the people he met and the challenges they face, and Sacco’s illustrations of residents narrating their own life stories. Though these visual segments are poorly integrated into the book, they are engaging and well-suited to the oral-history format; I found myself wishing there were more of them.

There are powerful textual moments in Days, too: the depiction of Whiteclay, NE, a block-and-a-half-long “town” that exists to sell beer to the residents of the Indian reservation across the South Dakota line; a glimpse of the squalid trailers inhabited by the Immokalee farm workers; a plaintive interview with three unemployed West Virginians, roommates in a crowded house purchased with FEMA money, one of whom dies of an overdose seven weeks after Hedges’s visit. These are people who don’t often make the news, and Hedges and Sacco deserve praise for finding them and chronicling their predicaments.

But Hedges can’t resist veering into manifesto mode, which soon becomes tiresome. After a moving segment about a West Virginia woman whose house is threatened by landslides caused by strip-mining, Hedges unloads this soliloquy:

As [societies] begin to break down, the terrified and confused population withdraws from reality, unable to acknowledge their fragility and impending collapse. The elites retreat into isolated compounds, whether at Versailles, the Forbidden City, or modern palatial estates. They indulge in unchecked hedonism, the accumulation of wealth, and extravagant consumption. The suffering masses are repressed with greater and greater ferocity. Resources are depleted until they are exhausted. And then the hollowed-out edifice collapses.

The entire book is like this. It reads like 300 pages of Studs Terkel constantly being interrupted by an overcaffeinated Howard Zinn.

As a result, the book’s human portraits too often seem less important than the political frame in which they hang. The problem, I think, is that Hedges and Sacco set out not to document the state of a gut-shot nation, but to demonstrate that corporate greed is the finger on the trigger. To that end, and to its ultimate demerit, the book consistently reduces its subjects to the sum of their miseries, and excludes anything that would hint at a diversity of experience. Hedges and Sacco talk to all the prostitutes and drug casualties they can find, but to few people who might complicate the pictures of these communities and the economic forces that made them the way they are. In their haste to name villains and victims, they neglect the nuance of reality.

The Camden chapter is particularly galling. The authors take pains to emphasize the post-industrial gloom of the city, which is across the Delaware River from Philadelphia. (Compared to Camden, West Baltimore looks like West Egg.) Yet the portrait feels insufficiently complex. Hedges and Sacco casually dismiss generations’ worth of minority civic activism with a flippant line about “compliant black elites whose loyalty rarely extended beyond their own corrupt inner circle”; they assert that, in Camden, “the world is divided between the prey and the predators,” thus reducing urban poverty to an Animal Planet documentary. They refuse to grant Camdenites any sort of agency, and it just rings false.

In 2010, a young urban planner named Gayle Christiansen chronicled several efforts at urban renewal in Camden, reporting on entrepreneurs and small-business owners who were attempting to revitalize their neighborhoods, one shoe shop and construction company at a time. These efforts—which ultimately may not succeed—are as telling as Days’s compendium of the city’s unalloyed woes. It’s not that Hedges and Sacco should balance every grim story with a hopeful one. But misery and hope coexist, and occasionally intersect. Camden is a third-world setting, but it is filled with people acting on first-world ambitions, and this is as much a part of Camden’s story as the crack houses and hookers.

Throughout the book, you get the sense that Hedges and Sacco looked just hard enough to find the evidence to support their thesis. And, yes, the book is a polemic, meant to decry unjust policies and processes and galvanize public protest against them. But it uses people to make its points, and there’s something off-putting about oversimplifying real lives to support what is ultimately a political argument. When writing about people who are so far out of society’s mainstream—people who are reduced and stereotyped by everyone they meet—there is a moral obligation to write about the person, not just his or her circumstances. I wonder how many of Hedges and Sacco’s subjects would recognize themselves in Days?

To see a larger version of this image, click here.

In a book ostensibly about people who live on the margins, the person we hear the most from is Princeton resident Chris Hedges. I respect that, to a point. Every story reflects its teller, and Hedges is open about his allegiances. But he is injudicious, and the excesses ultimately sink this well-meaning, well-reported book. He is there, for instance, to underscore a section about Native-American poverty with a clumsy “The tyranny we imposed on others is now being imposed on us”; he is there in the coal-darkened West Virginia hinterlands, a landscape where misery can speak for itself, asserting that “those who carry out this pillage probably believe they can outrun their own destructiveness. They think that their wealth, privilege, and gated communities will save them.” It is as if he didn’t trust that we’d get his point, so he pounds it home, page after page after page, with a constant, You have nothing to lose but your chaaiiins!

It’s exhausting, and I say this as a pro-labor zealot who agrees that corporate excess has crippled the working class. American society has failed in spectacular fashion, and it’s good that journalists are venturing out to record the wreckage. But the best work Hedges did for the Times in, say, Bosnia, proved that when the evidence of tragedy is so obvious and overwhelming, a good reporter need only describe it and let the facts speak for themselves.

One can’t help comparing the book to Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, the Walker Evans-James Agee collaboration that profiled three southern sharecropper families at the tail end of the Great Depression; its subjects demand your empathy, but never your pity. Or, more recently, to 2011’s Someplace Like America, in which photographer Michael Williamson and journalist Dale Maharidge chronicled their own cross-country poverty tour. In that book’s introduction, Maharidge reflects on the surprising tenacity and resilience he saw in the eyes of American’s junkies, squatters, laborers, and dreamers. They have been battered, but they are not beaten. “You cannot defeat people with eyes like these,” he writes.

But throughout Days, in the oral histories and the illustrations, the subjects’ eyes are downcast or vacant, as if awaiting either a savior or the guillotine, whichever comes quicker. (The only smiles and exuberance come in Sacco’s sketches that accompany the final chapter, a segment on Occupy Wall Street in which the protests are compared to the actions that toppled Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu and the Berlin Wall.) Hedges and Sacco looked America in the eye, and maybe this is what they saw. But it doesn’t feel like the whole picture.

Justin Peters is editor-at-large of the Columbia Journalism Review.