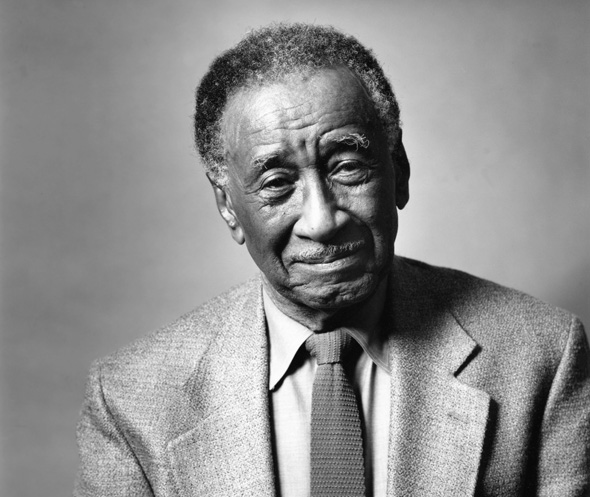

Editor’s note: Essayist, critic, and novelist Albert Murray died on Sunday at his home in Harlem. He was 97. Earlier this year, James Marcus, deputy editor of Harper’s Magazine, reread Murray’s South to a Very Old Place (1971). In his review below, Marcus calls the classic work an “anti-travel book”–one in which Murray “puts the torch to every bit of received wisdom about the [American South] and its racial conundrums.” — CJR 8/22/13

There is nothing quite so liberating for a journalist as failing to carry out an assignment. I’m not talking about a blown deadline or minor change in game plan–I mean missing the original target by such a wide margin that it’s clear the writer should have been aiming elsewhere in the first place. And there is no better example of such a fortuitous misfire than Albert Murray’s South to a Very Old Place (1971). The book was first assigned as a rueful tour of the American South, aimed primarily at northern readers who might never set foot below the Mason-Dixon line. Instead Murray produced a kind of anti-travel book, in which the observable facts are constantly eclipsed by the author’s memories and associations–even as he puts the torch to every bit of received wisdom about the region and its racial conundrums.

The germ of the book was a commission from Harper’s Magazine back in 1969, when Willie Morris ruled the roost and his traditional sense of literary decorum was giving way to the more bumptious vibe of the New Journalists. The original idea was that Murray, an Alabama native who lived in Harlem, would take a swing through the South to talk with the rising generation of newspapermen and writers, including Edwin Yoder, Marshall Frady, Joe Cumming, Shelby Foote, and Walker Percy. All of these men were white. Murray, who was black, seemed intent on using his conversations with them as a cultural and intellectual barometer.

This was a shrewd idea, give the drastic atmospheric changes then under way in the region. The South had already begun its reluctant transformation in the wake of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The same year that Murray took his trip, Charles Evers became the first black mayor in Mississippi since Reconstruction. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court ordered the immediate desegregation of 33 Mississippi school districts, whose foot-dragging interpretation of “all deliberate speed” was essentially an act of defiance. Progress, and a dogged determination to squash it, were visible everywhere. By talking to white southerners who were also indisputable progressives, Murray may have hoped for a fresh spin on what was still the American dilemma.

At 53, he had published relatively little. Almost two decades in the U.S. Air Force, with postings all over the country and abroad, had put a crimp in Murray’s career as a writer. During his military service, he tinkered with a novel, part of which appeared in New World Writing in 1953. And once he left the Air Force and moved to New York City in 1962, Murray began contributing to The New Leader, Life, and Harper’s, which ran a short story called “Stonewall Jackson’s Waterloo” in 1969. Yet his track record was still fairly skimpy when he floated his idea for a Deep South odyssey.

No matter. Morris was impressed by Murray, whom he had met through Ralph Ellison. Both, Morris would later recall, refused to accept any prefabricated notions about race, politics, and identity. It was Ellison “and our mutual friend Al Murray, also a Negro writer from the South and a former teacher at Tuskegee, who suggested to me as much as anyone else I had ever known the extent to which the easy abstractions, the outsider’s judgment of what one ought to feel, had simplified and dogmatized and hence dulled my own perceptions as an outlander in the East.”

Harper’s, meanwhile, was about to launch a series called Going Home in America, which would send a motley crew of writers on roots-excavating forays to Minnesota (Midge Decter), Michigan (John Thompson), and Kentucky (Elizabeth Hardwick). And Murray’s proposal was more or less folded into the series, at least in Willie Morris’s mind. So Murray picked up his travel advance and set off on his journey, “not as a reporter as such and even less as an ultra gung-ho black black spokesman but rather as a Remus-derived, book-oriented downhome boy.”

That self-description alone suggests that conventional journalistic practice has been tossed out the window. Another clue that Murray’s expedition will not proceed by normal means: his first stop is New Haven. That dour Connecticut city is not, he allows, part of the Deep South. But the Yale campus “has some very special downhome dimensions indeed these days,” thanks to the presence of Robert Penn Warren and C. Vann Woodward. Which is to say that home is a more portable concept than we might think–that it’s primarily a mental construct, ready to be unpacked whenever and wherever the imaginary traveler cares to rest his bones.

Murray, of course, had already tipped his hand on the very first page of the book. Going home, he writes, “has probably always had as much if not more to do with people as with landmarks and place names and locations on maps and mileage charts.” So it makes sense that having sought out two southerners at Yale–a “veritable citadel of Yankeedom”–Murray immediately identifies them with two figures from his childhood. Woodward, the distinguished author of The Strange Career of Jim Crow, is a dead ringer for an old Mobile insurance agent. And Warren evokes a ginger-haired auto mechanic known as Filling Station Red.

Murray wasn’t really there for a stroll down some honeysuckle-scented memory lane. With Woodward he took up the hot-button topic of antebellum “house slaves”–whom black nationalists were then vilifying as traitorous Uncle Toms for having supposedly savored the perks of plantation life while the “field slaves” stewed in their cabins. (Woodward, like Murray, found the distinction specious and misleading.) In Warren’s office, the conversation wandered from Joel Chandler Harris’s Uncle Remus tales to Frederick Douglass to the passel of Nashville poets who dubbed themselves the “Fugitives” during the 1920s.

What Murray was after in each case was an alternative to what he called the “folklore of white supremacy and [the] fakelore of black pathology.” To his mind, black Americans of the late 1960s were caught in an ideological squeeze play. On one side were the statistical, cookie-cutter theories advanced by white sociologists, which suggested that the black experience in America was primarily a hotbed of “frustration and crime, degradation, emasculation, and self-hatred.” On the other side was the Black Power movement, with its separatism, fire-breathing militancy, and increasing contempt for mainstream civil-rights crusaders like Martin Luther King Jr.

Murray resisted both. The back-to-Africa rhetoric struck him as no less absurd than the infantilizing analysis of ghetto life. He believed instead that “American culture, even in its most rigidly segregated precincts, is patently and irrevocably composite”–that we were a black-and-white nation, in which the fate of the two races was forever intertwined. American Negroes (the term Murray preferred) were full participants in the American enterprise.

This seems relatively mild as such statements go–the sort of bumper-sticker piety you might see on a passing Volvo. But during the late 1960s, these were fighting words, and Murray would articulate them over and over in South to a Very Old Place. It wasn’t merely that he enjoyed butting heads with his opponents (although he did). He was also trying to convey a deeper truth about life in the American South, which he thought was invisible to Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Malcolm X alike. Murray had no intention of sweeping the historic crime of slavery under the carpet, nor of soft-pedaling its destructive impact on black Americans. But he refused to view them as outsiders grafted onto some sort of Anglo-Saxon armature. No, they had gotten in on the ground floor, and their resilience and ingenuity in the face of epochal misery was now “indigenous to the United States, along with the Yankee tradition and that of the backwoodsman.” They were, as he liked to say, Omni-Americans–as were we all.

Leaving New Haven behind him, Murray finally heads south. In North Carolina, he drops by the Greensboro Daily News to interview its associate editor, Edwin Yoder. He is struck by the young newspaperman’s temperament, which he describes in typically additive fashion as “seed-store-feed-store plus courthouse square plus Chapel Hill plus Oxford Rhodes scholar.” But like Woodward and Warren before him, Yoder is hardly visible (or audible) during the conversation, having been displaced by the whirring mechanism of Murray’s free-associative fancy.

Yoder reminds him of an earlier newsman and diagnostician of the American South, Jonathan Daniels. Which reminds him in turn of his first trip out into the great world as a Tuskegee graduate in 1939, when he missed his bus connection in Columbus, GA, and “spent the night on a couch in the red-velvet-draped, tenderloin-gothic, incense-sultry sickroom of the legendary but then long since bedridden Ma Rainey.” (How typical of Murray to toss off that last anecdote, which many a writer would have milked for a novel-length slab of pathos!) Which reminds him in turn of Faulkner, and then of Thomas Wolfe: two more Southern boys endlessly exploring the riddle of their own origins.

Murray’s next stop is Atlanta, where he visits Joe Cumming, the local Newsweek bureau chief. Cumming, we are told, “is at work on one of Newsweek‘s periodic roundup reports on the progress of the so-called black revolution.” And unlike Yoder, he manages to get in an occasional word edgewise. But as usual, the real action is elsewhere, as Murray pulls another contrarian ace from his sleeve. Tokenism, he argues, is good. “[W]hen you are talking about revolutionary change, tokens and rituals are often more important than huge quantities.” And to bear out this argument, he spies none other than Atlanta Braves slugger Hank Aaron on the sidewalk–a “statistically unique, statistically insignificant, but no less symbolically overwhelming figure.”

It should be clear by now that we’re not going to learn much about the South’s rising generation of white newspapermen. No doubt Murray, who was celebrated as a champion conversationalist–in a 1996 New Yorker profile, Henry Louis Gates Jr. noted his “astonishing gift of verbal fluency”–had some fascinating exchanges with them. But even if the author had carefully taped and transcribed this material, it would have produced a modest report for Harper’s. And I’m guessing that after 20 years of delay, during which he saw his old friend Ralph Ellison race to the head of the literary pack with Invisible Man, Murray was eager to open up the throttle.

So instead of the reportage he had promised Willie Morris–and instead of the short, pugnacious New Leader pieces he would soon collect in The Omni-Americans: Black Experience and American Culture (1970)–Murray aimed at something more ambitious. In his rearview mirror were the modernist giants: Faulkner, Joyce, Hemingway, Auden, Proust. There were also a number of formative critics, including Kenneth Burke, Constance Rourke, and that supremely British eccentric Lord Raglan, whose The Hero: A Study in Tradition, Myth, and Drama (1936) shaped many of Murray’s ideas about literary art.

What he took from these models, which were literary rather than journalistic, was a belief in elaborately stylized prose and deep-dish subjectivity. Not so different, you might say, from the New Journalists who were just then hitting their stride–especially the other Tom Wolfe, who had long since knocked down the Chinese wall between himself and what he was describing. But Murray went further, and made up his own rules. You argued with others but primarily with yourself. You observed the world with finicky accuracy but then transformed it into art. And the cartwheeling, conversational tone of his sentences was his alone, as were the onrushing rhythms and the pungent, hyphenated adjectives marching along in single file–or more often sprinting.

In the initial chapters of South to a Very Old Place, these qualities are something of a mixed blessing. Murray’s musings are comical and attractively cantankerous, yet they seem to exist in a vacuum–in the sealed chamber of his own sensibility. He can’t stop ruminating, arguing, saddling up one hobbyhorse after another: house slaves, sociology, tokenism, black matriarchy, protest fiction. The reader becomes increasingly desperate for some hard evidence that Murray has actually left his apartment on Lenox Terrace.

In the second half of the book, however, something marvelous happens: The outside world finally gets equal billing. Perhaps Murray sensed the need to dilute his argumentation with some sinus-clearing actuality. It also seems likely that his personal connection to Tuskegee and Mobile (where he grew up) made him more impressionable and open to his surroundings. In any case, while en route to Tuskegee, Murray is overwhelmed by memories. He recalls his first Greyhound bus ride to the college, the songs that were playing on the radio that summer, and “the whiteness of academic columns as you saw them through the flat preautumnal greenness of the elms lining Campus Avenue.”

Some of these memories, oddly enough, are ascribed to other Tuskegee students of the era, as if Murray can creep out of his solipsistic shell only by degrees. And some have a collegiate friskiness to them, which seems only appropriate. Here, for example, Murray runs down the faculty roster, culminating in that agricultural wizard George Washington Carver, who was then so old that Henry Ford would soon pay to have an elevator installed in Carver’s Tuskegee lodgings:

They all will remember W. Henri Payne with his brownskin Frenchman’s moustache whether they took French or not that year. They will remember Alphonse Henningburg and his beautiful wife. Nor will anybody have forgotten that the only way to repeat anything Dr. Carver said was to imitate him in as high a pitch as possible (adding precisely enunciated dirty words which would have horrified him: “They ask me: ‘Dr. Carver what makes rubber stretch?’ and I say to them quite frankly I don’t cop what the fuck makes that shit act up like that, I don’t dig no rubber-stretching shit. I dig peanuts, I dig potatoes.”)

It’s instructive to compare Murray’s Tuskegee interlude with the one V. S. Naipaul included almost 20 years later in A Turn in the South–after Murray himself prepped him for the visit! Naipaul’s account is careful and cumulative. He gets the facts, elicits testimony from a couple of locals, and as he explores the broiling interior of Tuskegee’s Dorothy Hall, notes that the “colors in the hot paneled club upstairs were like the colors of a gentlemen’s club.” The irony is unmistakable, but also quiet: a murmur. Whereas Murray is sweeping, breathless, atmospheric. He wants the feeling of the place, and the memories of it, and he wants to surprise himself in the act of remembering.

In Mobile, at last, he is really back home. There the Scott Paper Towel factory has gobbled up the landscape of his youth like a “storybook dragon disguised as a wide-sprawling, foul-smelling, smoke-chugging factory, a not really ugly mechanical monster now squatting along old Blackshear Mill Road.” There Murray wanders the streets and connects with half-remembered acquaintances. And there, for the first time in the book, other voices climb confidently into the driver’s seat.

In fact, the chapter is jammed with lengthy, back-porch soliloquies. Murray seldom identifies who is talking. And given the preoccupations of the speakers, which happen to be his preoccupations, it’s pretty clear that he orchestrated and intensified what they had to say (much as he would later channel Count Basie in the bandleader’s autobiography, Good Morning Blues). In any case, the results are frequently hilarious. One such speaker gives the back of his hand to the Black Power dream of African repatriation. The Africans, he says, will

take one look at them goddam jive-time Zulu haircuts and them forty-dollar hand-made shoes and they going to lock your American ass up in one of them same old slave-trading jails they put our ancestors in, and they going to have you writing letters back over here to this same old dog-ass white man in the United States of America asking for money. Hey, wait. Hey, listen to this. Ain’t going to let them get no further than the goddam waterfront. They go lock them up with a goddam Sears, Roebuck catalogue. I’m talking about right on the dock, man, and have them making out order blanks to Congress for Cocolas and transistors, and comic books, cowboy boots and white side walls and helicopters and all that stuff.

This is identity politics as black comedy, with some incidental buckshot fired at American-style consumerism. It is also a sly bit of self-mockery, since Murray himself was an avid consumer of fine clothes, fine art, audio equipment, and probably the occasional transistor. And as a boyhood admirer of Tom Mix, he must have longed for the cowboy boots as well. Maybe he should have shared the microphone more often.

Murray’s chronicle of his journey never appeared in Harper’s. Perhaps Willie Morris found it too weird and wandering for his taste. It was one thing, after all, to devote an entire issue of the magazine to the heavy-breathing theatrics of Norman Mailer’s “The Prisoner of Sex,” quite another to publish Murray’s unclassifiable (and occasionally unreadable) circuit of the South. More to the point, Morris himself was forced out in 1971. The owners argued that revenue was down and blamed the editor’s penchant for long, liberal, supposedly ad-repelling articles. In that climate, it’s no wonder that the raw materials for South to a Very Old Place got spiked.

Murray wrote the book anyway. When South to a Very Old Place was published in 1971, it was nominated for the National Book Award, and reviewed most prominently by a young novelist named Toni Morrison. She praised Murray’s resistance to racial stereotypes and his mixture of “tender familiarity and brutish alienation.” What Morrison didn’t like was his chuckling disdain for “the Afro- part of Afro-Americans”–i.e., his unwillingness to view himself as part of a great diaspora–as well as the short shrift he gave to black nationalism.

Who was right? Murray’s voice is so persuasive that it’s tempting to declare him the victor, but the argument is no simpler now than it was then. In a way, these two formidable intellects were restaging the old quarrel between Booker T. Washington, with his emphasis on stoic self-reliance, and W. E. B. Du Bois, who crusaded relentlessly for equal rights at home and Pan-African solidarity abroad. That Murray would opt for the former position is no surprise–he was a product of Tuskegee, which Washington had founded in 1881. As for Morrison, she was not only a generation younger, but had taught and mentored such firebrands as Stokely Carmichael, who made the phrase “Black Power” part of the popular lexicon. A meeting of the minds was unlikely.

Morrison would go on to celebrity, success, and the Nobel Prize. (Murray, never a huge Morrison fan, told Gates that the award was “tainted with do-goodism.”) His own path was more circuitous, and never quite yielded the sort of fame that he deserved. Still, Murray would publish many volumes of fiction and criticism, as well as sui-generis productions like Stomping the Blues (1976), a euphoric study of American music. And his influence on the next generation of black intellectuals, including Stanley Crouch, Cornel West, and Stephen Carter, was enormous. They didn’t necessarily endorse all of Murray’s ideas, but they inherited his allergic reaction to received wisdom. They also saw their own role in the nation’s cultural life as central–they were, as Murray put it to Robert Boynton in 1995, “just a bunch of Negroes trying to save America.”

And it all began with South to a Very Old Place. The book’s speed, intensity, tenderness, and pugilistic laughter remain as fresh as ever. It is by no means a perfect creation. There are stretches where you wish the author would simply stop talking and let the particulars speak for themselves. Blazing a fresh trail through the briar patch, turning every assertion about race and identity and the storied South on its head, he seems almost determined to leave the reader behind. Yet you keep turning the pages, eager as ever to accompany Murray around the next bend and to share with him the purest of all literary intoxicants: self-discovery.

James Marcus is the deputy editor of Harper’s Magazine. His next book, Glad to the Brink of Fear: A Portrait of Emerson in Eighteen Installments, will be published in 2015.