Discounting cash-in reunions, studio sessions with bank robber Ronnie Biggs, and the like, The Sex Pistols last played in January 1978 at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco. Their useful life ended unimprovably, with singer Johnny Rotten asking the crowd, “Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated?” and then stalking off the stage.

Among the crowd that night was Greil Marcus, a thirty-two-year-old critic and author on assignment for Rolling Stone. His review of the Winterland concert ran in the March 9, 1978 edition, which featured an alarmingly vacant Jane Fonda on the cover, and was perfunctory at best. In it, he praises the Pistols’ energy and bravado, notes the bad behavior of certain attendees, and infers from Rotten’s exit the conclusion, at long last, of a short, anomalous era in pop music.

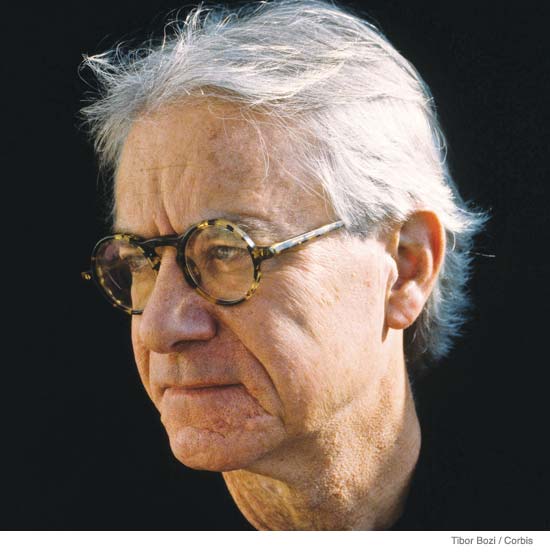

An owlish figure who studied political science as a graduate student at Berkeley and writes like it, Marcus, then as now, was known for his focus on the iconography and secret history of rock and roll. Marcus began writing about Bob Dylan in 1968, the exact point at which he lost his relevance, and Marcus has somehow managed to since write enough fawning prose about him to fill a recently released anthology that carries a shipping weight of 1.4 pounds—in addition to two other dense book-length studies. With that record, Marcus may have been the single critic in the United States least likely to write the best book about what punk rock meant and why, all these years later, anyone should care.

Peers and rivals such as Lester Bangs and Robert Christgau were so entranced by this music and the potential it held to redeem all the cashiered promises pop music made in the late 1960s—promises, essentially, that radio songs could create a new way of living, an escape from a world of slicks and frauds—that they seemed to remake themselves in response to it. Marcus was a more wary figure. He was seemingly more comfortable with old, forgotten blues and folk records than with the Billboard 100, and certainly not one to attempt, as Bangs did, to himself become one of the madding crowd. In his review of the Pistols’ last show, there is a tangible feeling of unease, a sense that this was not a place he was meant to be.

And yet, perhaps because punk traded so heavily on such feelings of discomfiture, it was in fact his perfect match. Originally published in 1993, Marcus’s Ranters and Crowd Pleasers: Punk in Pop Music, 1977-92 is a collection of occasional journalism comprising dozens of columns and features written for such outlets as Rolling Stone, The Village Voice, and Artforum. It is the one book to read if you want to really know about punk.

So far as punk was anything more than pop style—and most of even the good stuff was not—it was a response to a question: If you could say anything, what would it be? Today, that question doesn’t carry the same implications it once did, but the brief early glory that ended on stage at the Winterland Ballroom represented the temporary triumph of inarticulate free expression over a world dominated by glad-handers and smooth-talkers. It may be that there were no more than a half dozen great records among hundreds in that first wave; the point was that the records were real at all. Their very existence spelled out a horrifically loud rejection of all sorts of smug mendacity. Anyone can be a musician, they said. You don’t need fancy clothes and a contract. You don’t even have to know how to play.

The main line on punk ends in its total, miserable failure. As it turns out, most people who make a fetish of amateurism are making excuses to stall for time while they learn what they’re doing. Steve Jones, the Pistols’ guitarist, went on to a career as a Los Angeles session man, a real pro who landed numbers on Miami Vice soundtracks and actually started up a band called The Professionals. This wasn’t selling out. This is who he was all along, and so too most of his peers and progeny, who mustered up the guts to say something only to find they had nothing at all to say.

Most of the writing on punk holds that it was, ultimately, a glimpse at an uncompromising future that never actually arrived. Unlike Bangs and Christgau, though, who loved punk for what it wasn’t—soft, slow, tentative—Marcus saw it for what it actually was. For him it was a sensibility, and not a theory, one that more than anything was about a vague sense that the world was not as it should be. And this is likely why he was one of the few to notice that the Winterland show was not the end of anything at all.

Punk—call it loud, fast rock and roll played in the mid- to late-1970s by the first generation to whom Bob Dylan and The Beatles were hoary old relics—was a lot of things. It was the inevitable result of some of the stranger musical experiments of the 1960s and the invention of cheap recording technology; it was an inchoate reaction to the same anxieties that would soon put Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher in office; it was the perfect cultural expression of eternal adolescent alienation; it was a fad. For a few months in 1976 and 1977, the papers and the television carried ominous warnings about feral youths listening to incomprehensible ranters who dyed their hair green and wanted to overthrow the government and set everything on fire. The Sex Pistols, who denounced the Queen as not even being human, were banned from the British airwaves; rock critics briefly exulted and then forgot about the whole thing.

Marcus shows no real concern with those few brief months in 1977 when punk was capital-I Important and every broadcast in England led with a picture of some young unfortunate with a safety pin through his face. Nor does he have anything much to say about the parallel scene in downtown New York, where, he notes, “most punks seemed to be auditioning for careers as something else.” He has little interest, in fact, in most of the canonical punk rock with which I was obsessed at age fourteen, when I cajoled my mother into buying this book for me, and with which any number of fourteen-year-olds are probably just as obsessed right now: Television, Minor Threat, Hüsker Dü, and the Minutemen aren’t mentioned at all, and the Ramones once, in a passing reference to their tiresome shtick.

What does interest him is a lot of strange music of which I’d never heard. Much of it I wouldn’t discover for many years, partly because many of the records were, quaint as it seems today, physically unavailable in the United States at a price I could pay, and partly because the heterodoxy of what he was describing was just intimidating: it was music I’d never heard anyone else speak up for, which seemed to come from a world at a right angle to the one I knew. Most of what he recommended was quite brilliant. These were (mainly) English groups with such fantastical names as Essential Logic (“imagine Alice forced to get a band together and play for the Red Queen…a modest, perfectly intentional demolition of the ability to take anything at face value”), Delta 5 (they “accept the inevitability of love but maintain their suspicions”), Gang of Four (“leisure as oppression, identity as product”), and The Mekons (“collective self-realization through playful art against a backdrop of social strife”).

Where the acts that I was listening to were generally working minor variations on a single theme of loud solipsism, these groups were imagining, and creating, a small and temporary utopia in short bursts, the place the singer Poly Styrene described when she sang about x-rays penetrating through a latex breeze. If I’d had the ear for them, I would have heard a way out of the charmless narcissism that had me holed up in my bedroom with Minor Threat blaring through my headphones. I didn’t, but then few people did. Marcus was one of them.

More alienated and politically astute than his fellow critics, Marcus was never put out by punk’s revolutionary posturing, and so never fixed on hair dye, safety pins, and moral panic as being anything worth much thought. He took anarchism and bad fashion as given, and kept listening after the scabrous youth of London were done with their fourteen minutes. What he heard showed that the conventional line on the music was totally wrong. The safety-pinned kids may have failed to do whatever it was they were supposed to do—overthrow the British monarchy? kill bad radio forever?—but it was exactly at this point that punk became interesting.

There were a lot of people in places like London, Leeds, and Los Angeles who did have something to say after all, and found in the music an idiom in which they could say it. “The story,” Marcus writes, “was always the same: the music made a promise that things did not have to be as they seemed, and some brave people set out to keep that promise for themselves.”

Take The Mekons. They started in 1977 at the University of Leeds as strictly a joke, more a students’ collective of almost two dozen pranksters and semi-musicians than a proper group. They vowed that they would never record, allow themselves to be photographed, or give interviews, and then cheerfully did all of it. They brought a couch inscribed with the word “spaceship” on stage with them. They sang absurd songs—their first single, “Never Been In A Riot,” consisted of a couple of chords and a drum roll, sounded like sucking the pulp out of a dead tooth, and was chiefly concerned with mocking The Clash’s risible claim to want a “White Riot.” (The Mekons did actually end up in a riot, fighting off a neo-fascist attack on a gay bar they frequented, which made the joke even better.) Beside this utter incompetence, the Pistols may as well have been Led Zeppelin or King Crimson.

The Clash, the most successful of the original punk bands, had slogans, communiqués, a tune in which they elevated an arrest for shooting pigeons into a cosmic attack on the idea of representative democracy. The Mekons had principles: “that anybody could do it; that we didn’t want to be stars; that there was no set group as such, anybody could get up and join in and instruments would be swapped around; that there’d be no distance between the audience and the band; that we were nobody special,” as guitarist Kevin Lycett once told the writer Simon Reynolds. What was in the hands of a great and yet thoroughly conventional band like The Clash a set of contrived rebel postures was something quite different for The Mekons. They actually meant what they were saying.

For Marcus, intensely focused as he was on music by people who quite deliberately had nothing to say at all, this sort of thing clearly came as true revelation. The old folk and blues acts with which he was obsessed meant nothing they said and probably paid it no attention; their lyrics were dusty inheritances. Their descendants, such as Dylan and The Band, loved dramatic poses and the sound of words. They were performers, assuming transient roles for the benefit of an audience.

For The Mekons, quite the opposite was true. They had no idea how to perform, no notion of what it meant; crude as it was, their music was pure, direct reaction to a time of upheaval. In it, Marcus heard “some hint here, some fragmentary cultural memory, of the Ranters, the possessed and sometimes naked heretics who defined the farthest reaches of extremism during the English Civil War.”

There is no such distance in his reaction to Gang of Four. The first time he saw them live, he reports, he left directly after their set despite having wanted to hear the headlining Buzzcocks for years. “I didn’t,” he writes, “want anything to interfere with what had just happened.” This was September 1979, and he had just seen probably the strongest group in the world, one which utterly overwhelmed him even before he could really understand what they were saying.

Preposterously, these four handsome young men had not only perfected an original and fantastically danceable sound that somehow married the bass-led rhythms of Jamaican dub to the jagged guitar of The Velvet Underground and was immediately identifiable as the purest sort of punk—while being clearly suited for radio. (While they were never much commercially, their style has underwritten numerous popular acts over the years.) They were also avowed neo-Marxists, steeped in the Frankfurt School and wary of the notion of individuality. A critic of Marcus’s dispositions could want little more.

“If this is the future of rock, I can’t wait,” Marcus wrote. Within months of first seeing the group he made his way to England to join them on tour and to report on what he called, with no evident irony, “Britain’s postpunk pop avant-garde.” “Don’t romanticize it,” he is warned by the head of Rough Trade, a leading label; he admirably fails.

The resulting long dispatch is the heart of the book. In it he sees a performance at a venue promoting a “Chile Solidarity Disco,” is lectured by an all-female quartet, The Raincoats, on the ways in which rock is inextricably bound to “the exclusion of women and the ghettoization of blacks,” comes to understand the financial structure of an independent record label, talks to the marvelous nineteen-year-old singer and saxophonist Lora Logic about punk as self-invention, and after asking the same pretentious questions I would like to have asked them, comes to understand Gang of Four as “the voice of false consciousness in rebellion against itself, and, almost simultaneously, the voice of resistance to that rebellion, the voice of a yearning for accommodation.” This was, in every way, a group that fulfilled every promise ever made on The Sex Pistols’ behalf.

None of it mattered for those who didn’t do their own digging in the days before Google and torrent sites, when the surface was not easily chipped, and this is the source, presumably, of much of Marcus’s desperate energy and passion. He wanted people to know how good Gang of Four were; he wanted them to be popular. One would not write this way about a fringe act today, when there is no broad consensus and even the most saleable act aims only to hit a niche, but there was a sort of bravery in Marcus’s exertions. Other critics wanted to change what people heard; Marcus wanted people to change the way they heard.

He, and the band’s other backers, failed: among people who care about such things, Gang of Four is hardly any kind of obscurity, but they topped out at number fifty-eight on the UK charts and did even worse in the States. This was, writ small, the failure of punk, which was after all a popular form and not a pretext for referencing Theodor Adorno. Even when its best got everything perfectly right, no one really cared.

This was on some level the subject of what was probably punk’s finest moment, The Mekons’ 1985 return from oblivion with Fear and Whiskey, in my opinion the best record of that decade. It is a lot of things: a great collection of drinking songs, a dark meditation on the death of labor and of the promise of America, and the first and best and most convincing of what would eventually be far too many fusions of punk rock and country. (The Mekons sold even less than Gang of Four, but are just as responsible for vast amounts of terrible music made by other people.)

As Marcus writes, this record “carries an unmistakable undertone of self-mockery, of humiliation, of shame, because it cannot count. Fear and Whiskey is just fear and whiskey, nervousness and oblivion; it is the music of people who are sure that the world they cannot change will never find a place for them, that what they have to say will never be heard.” It is the best record about a terribly modern fear, that in the vast cacophony of people liberated to say whatever it is they feel they need to say, no one will ever hear what you have to say.

Improbably, given The Mekons’ origins as the sloppiest and most amateurish band in the world, Fear and Whiskey was just the first of an uninterrupted string of wonderful records that continues to this day. They are not really a going concern and not quite a business, but every so often they take a short tour or release a new record, and their audience, which barely rises to the size of a cult, takes it as a gift. All along that was the future of rock: a great old band in a small club, cheerfully oblivious to their utter obscurity and everything but their lives and what compelled them to start in on music at all.

Marcus never comes to a direct answer to the question of whether this is failure, and if so what kind it is, but he does offer an oblique one. Along with The Mekons and The Clash and a host of other groups, many of them just the kind I admired most at age fourteen (X, Sonic Youth, Black Flag), these pieces trace the careers of two singers who were, at most, fellow travelers: Elvis Costello and Bruce Springsteen, the crowd pleasers of the title. In Costello, he sees someone trying and failing to express a single idea of surpassing importance: “that fascism, far from being defeated in 1945, simply went underground, where it now functions as the political unconscious of the West.” In Springsteen, he sees something like the living embodiment of rock music, his anthemic treatments of working class immiseration and his stark acoustic ballads of murder on the high plains the natural and fitting obverse of, say, The Mekons’ obsession with striking coal miners.

“The Sex Pistols’ first achievement,” he writes in his introduction, “was to burn rock ‘n’ roll down to essentials of noise; if punk ever really ended, it was in the middle of its tale, when two singers from whom most punk chroniclers would withhold the name burned punk down to something close to silence.” It is a striking claim, and in it one can just discern an answer to the problem posed by The Mekons. There is a worse thing than not to be heard and to not have an audience, it would go; it is to be heard and not understood, to have a vast audience that simply doesn’t care what you have to say. (This is a fate with which a Rolling Stone writer whose intricate, dense articles on various rock genealogies are skimmed or skipped by millions of subscribers eager to make their way to the latest interview with Jackson Browne is perhaps unusually sympathetic.) And there is a real victory in freeing oneself from the need for validation, in being content with an audience that may be small but has ears to hear you.

For as long as he’s been writing, Marcus has been generally less interested in his actual subjects than in the invention of resonant mythologies about them. This is dangerous for someone writing about simple music, and leaves him prone to unconvincing theoretical disquisitions on such ideas as how old Dylan records about getting drunk fit in a line tracing back to the Great Awakening. (Lipstick Traces, his other book on punk, shows the danger by tracing the connection between the Pistols and the French situationists; it is nowhere near as bracing as his reportage on the music.) It’s one thing to write about pop records and live performances as if they are strictly cultural artifacts, and something very different to forget, as he sometimes has when not faced with the immediate presence of an act as powerful as Gang of Four, that this is a fiction and a contrivance.

It says a lot about the power of this music that it forced him to remember, and to show just how sharp a thinker he can be at his best. Perhaps fittingly, unlike several of his less compelling ones, this book has been flitting in and out of print in various editions and under various titles since it was published. Like its subjects, it hasn’t been heard widely; one hopes it’s heard well.

Tim Marchman , a sportswriter, will be a 2012 Knight-Wallace Fellow at the University of Michigan.