Journalists have always been parochial. Reporters tend to focus on their story, their beat; newsworthiness depends on the narrow interests of a community. In some ways, the internet has pulled us out of our isolated spheres and offered the potential for vastly growing our audiences, yet for most outlets, that expansion has not happened. The news has largely remained local—or at least has aimed to stay that way in light of brutal economic threats.

But things are changing. We face, at once, the rapid, technology-fueled spread of disinformation; the rise of authoritarianism as a response to worsening income inequality; and the broadening fear of demographic shifts in countries around the world. The press has been tasked with covering these stories, and has been caught in their nets.

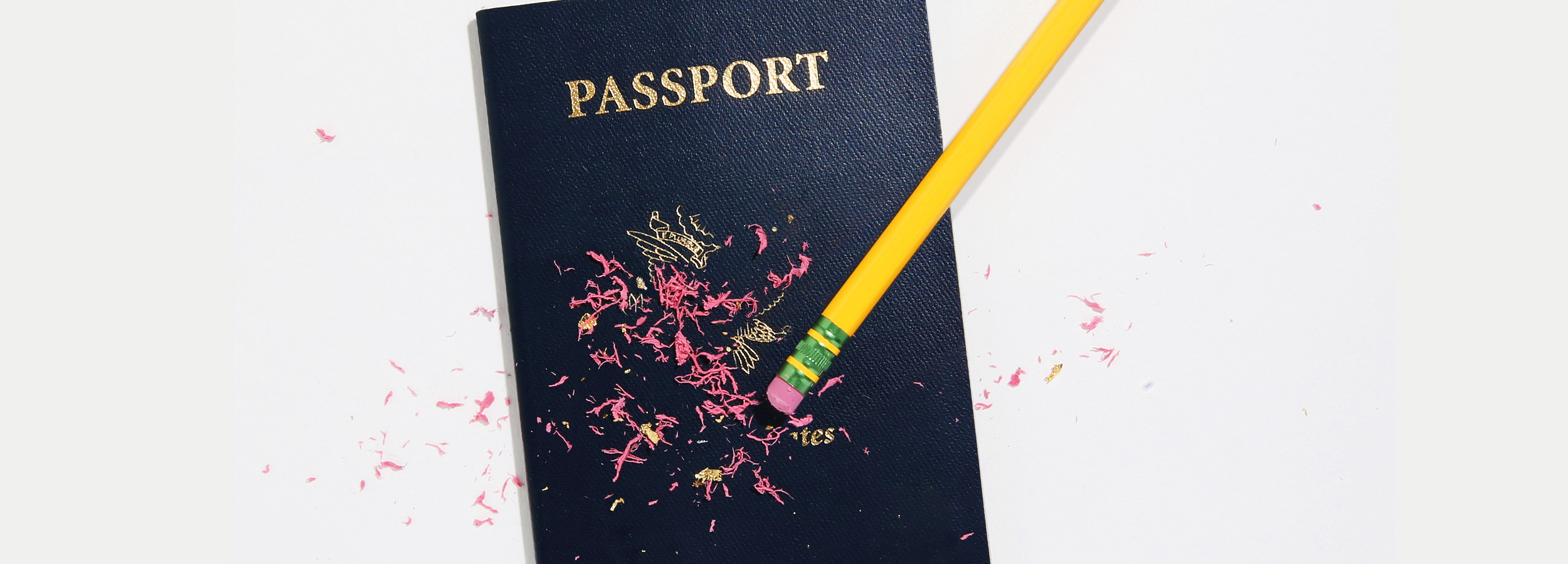

The proliferation of misinformation has been particularly transformative. In the hazy months following the election of Donald Trump to the White House in 2016, one of the astonishing facts with which journalists had to grapple (and there were so many) was that Russia had targeted the United States with fake and misleading stories in an attempt to help Trump win. The idea sounded dystopian, and it was: Russian hackers at content mills had flooded social media, primarily Facebook, with untruths intended at once to sow disorder in the American electorate—steering voters to Trump, who played on their angst and bigotry—and to discredit legitimate journalism.

As we’ve seen disinformation metastasize, real journalism has been dragged under the chaos.

By using the same social-media pathways that mainstream news organizations had come to depend on (in grave error), the Russian disinformation campaign was able to tarnish us all. Fraud and facts commingled. Trust in news outlets eroded. Trump shouted “Fake news!” and Americans saw confusion unspool on their computers. Sometimes readers found legitimate news that Trump tried to discredit because he disliked how it made him look; other times, they found the intentional misframing of information to distort the truth; on many occasions, they found what was simply rank nonsense.

As we’ve seen disinformation metastasize around the world, real journalism has been dragged under the chaos. We’ve seen it in Myanmar and Brazil, Sri Lanka and New Zealand, sometimes in orchestrated campaigns that bear the fingerprints of state actors, sometimes in one-off manifestos from deranged minds. The result is always the same: false reports poison the very platforms that house real journalism. No one in the press is safe from seeing her earnest, diligent work displayed amid the flotsam.

Journalists were just beginning to contend with the scope of this problem when word came that Jamal Khashoggi, a Saudi columnist for The Washington Post, had been kidnapped and murdered in his country’s Turkish embassy. Khashoggi was a serious journalist—deeply thoughtful, compassionate, open-minded. He bemoaned the curse of governments exerting local control by way of disinformation and censorship. In response to his death—and his complaint—Trump rolled his eyes. Details of Khashoggi’s murder remain unexplained, despite the best efforts of his colleagues at the Post to bring his killers to justice.

What reporter anywhere is safe? Our parochialism now seems quaint, a relic from a time when autocrats weren’t weaponizing information that could be disseminated by the internet at rapid speed, to the great profit of companies in Silicon Valley. We can still keep our noses pressed to computer screens, staying focused on our work, but every so often we have no choice but to sit up and recognize that we’re part of the world around us.

Here’s the good news: journalism has always been a tribe, and it turns out our tribe is a lot bigger than we might have thought. All of the attacks and the challenges that confront reporters are drawing us together. So when Maria Ressa, a founder of the news site Rappler, is threatened and detained for her courageous reporting in the Philippines, her voice becomes a rallying cry for our industry. When Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo, two Reuters reporters, are jailed for their work in Myanmar, their names become a hashtag for the media business and they are eventually freed. And when a group of committed journalists working at The Capital Gazette are gunned down in their newsroom, in Maryland, they hear from journalists around the world, all offering help. Our fraternity, stretching from one corner of the earth to the other, is tighter than ever.

It is heartening to know that the biggest challenges we face aren’t ours alone to shoulder. It’s easy to get lost in individual gloom over the threats to our profession, the decimation of local news, the toxicity of social media, the painfully slow march toward diversity and equality for women. But what we have found, in compiling this issue of CJR devoted to global journalism, is how journalists around the world are tackling the same problems at the same moment, in strikingly similar ways.

All news is local, as we know. Reading this issue, you may be both terrified at the scale of our shared concerns, while also encouraged by the fact that there are so many talented people devoted to overcoming them, in a vast, global effort. That raises the odds for us all, together, to find our way through the chaos.

Kyle Pope was the editor in chief and publisher of the Columbia Journalism Review. He is now executive director of strategic initiatives at Covering Climate Now.