On a Monday night in September, 2,000 people gathered at a theater off Times Square to watch five political journalists sit on a stage and talk about polls. The occasion was a live taping of the FiveThiryEight Elections Podcast, an almost unimaginably nerdy event for which attendees paid up to $100 per ticket. As members of the crowd sipped IPAs and cheered each jab at Donald Trump, the panel bantered over recent developments in the presidential race and issued predictions for the coming weeks.

With its reliance on polling data over source cultivation and number crunching over narrative, FiveThirtyEight, a website focused on statistical analysis of politics, economics, culture, and sports, is at the forefront of a shift in the way political journalism is practiced. At the live event, that change was perhaps best embodied in the youngest journalist on the panel, senior political writer and analyst Harry Enten.

At 28–his sobriquet, bestowed by colleagues, is “Whiz Kid”–Enten has emerged as one of the stars of FiveThirtyEight’s political coverage, drawing attention both for his sharp analysis and his unique personality. He is the sort of journalist whose facility for interpreting polling data, combining it with demographics and historical precedents, and communicating his conclusions precisely and accessibly inspires envy in slower-moving, more numerically-challenged thinkers. He is also the sort of person who will arrange to be interviewed in a diner, only to inform you that he prefers to ingest his meal supine. He will have his food packed at the end of your conversation, to be consumed later in bed.

Related: 7 photos that capture the absurdity of this election season

The meteoric success of young reporters whose capacity to process information seems to rival that of computers is nothing new. Ezra Klein, the wunderkind who began blogging for The Washington Post at 25 and has since become editor in chief of Vox, was among the early standouts. Nate Silver, who was 30 when he founded FiveThirtyEight, was another.

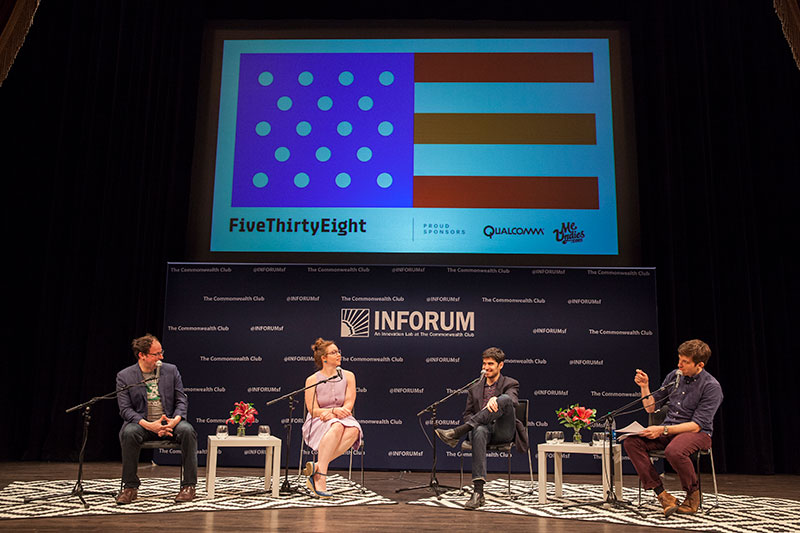

Nate Silver, Clare Malone, Harry Enten, and Jody Avirgan take the stage at San Francisco’s Herbst Theatre for the FiveThirtyEight Live podcast this June. (Peter DaSilva / ESPN Images)

This election cycle has amplified the voices of several Young Turks whose desk-bound, scientific-method approach to journalism cuts against the grain of more traditional reporting techniques. Even more so than four years ago, 2016 has showcased a crop of political reporters who take a dramatically different approach from the boys-on-the-bus ethos of earlier generations stretching from David Broder to Hunter S. Thompson through Dan Balz. Sites like FiveThirtyEight, Politico, Slate, and The New York Times’ The Upshot have embraced statistical analysis as an antidote to anecdotal extrapolation.

The rise of this sort of data journalism has its critics. Silver “does not take a side, except the side of no side,” wrote Leon Wieseltier just after FiveThirtyEight launched at ESPN. “He does not recognize the calling of, or grasp the need for, public reason; or rather, he cannot conceive of public reason except as an exercise in statistical analysis and data visualization.” For those on Wieseltier’s side of the argument, there is a feeling that something essential is lost when human decisions are reduced to data points, that data journalism is in some way bloodless and empty.

With backgrounds in statistical analysis rather than traditional journalism, both Enten and his boss, Silver, approach their work from a different perspective than most reporters. “There is a helpful ethos that Nate and Harry provide where they see themselves as outsiders to the media culture,” says Clare Malone, a senior political writer at FiveThirtyEight. “I think being an outsider, maybe you’re able to call B.S. a little easier. That’s a helpful role to have.”

Related: Nate Silver unloads on The New York Times

To anyone following the 2016 election, polling analysis and statistical examinations are inescapable. Conversations about good and bad polls, skewed polls, and polling “bumps” are ubiquitous. FiveThirtyEight is known for the fervor with which it embraces–and then slices and dices–these figures. But Enten, perhaps more than anyone else at the site, eschews the sort of sourcing and conversations from the campaign trail that have long been the bedrock of political journalism. He operates almost entirely from his computer, crunching figures, aggregating polling data, and searching for historical indicators. His pieces are full of numbers, an explanation of what those numbers mean, and a prediction about where they could be pointing.

“I have no problem with going around and talking with politicians and this, that, and the other,” Enten says. “But the idea of using yard signs when there are polls, the idea of taking one poll and running with it versus taking an aggregate of polls…” he trails off with an exasperated sigh.

I think being an outsider, maybe you’re able to call B.S. a little easier. That’s a helpful role to have.”

Enten’s mention of yard signs is no accident. The bête noire of data journalists is Peggy Noonan’s Wall Street Journal column from the day before the 2012 election. Noonan began by writing, “Nobody knows anything. Everyone’s guessing.” To statistics-minded journalists who had spent months building models and crunching data, this statement was tantamount to heresy. When Noonan went on to predict that Mitt Romney would squeak out a victory, citing the yard signs she’d seen in Florida as evidence, data journalists found the platonic ideal of everything they stood against.

Noonan’s naivete seems laughable now, but it’s worth noting that even the most sophisticated polls and analyses can be wrong or simply blind–as FiveThirtyEight’s was this year in failing to predict the remarkable staying power of Donald Trump. Elections are interesting in part because, even with the latest data wizardry, the preferences and desires of voters remain somewhat unfathomable, even to themselves.

“Nothing exceeds the value of shoe-leather reporting, given that politics is an essentially human endeavor and therefore can defy prediction and reason,” media reporter Jim Rutenberg wrote in a May New York Times column titled “The Republican Horse Race Is Over, and Journalism Lost.” Rutenberg blamed the entire field of data journalism for failing to help audiences make sense of the political chaos, and took aim at FiveThirtyEight specifically.

On the next FiveThirtyEight Elections Podcast, Nate Silver vigorously defended his approach while also analyzing why so many data journalists had erred in their predictions. “I acted like a pundit and screwed up on Donald Trump,” he later wrote, arguing that a site that has built its brand on analyzing data relied too heavily on subjective analysis and had given too much weight to so-called “fundamentals,” such as party endorsements, favorability ratings, and historical precedents.

All the more reason, Silver says, to prioritize numbers. “I find sometimes that campaign coverage is insufficiently skeptical because of having the reliance on the same group of several hundred people for quotes and for access,” he tells CJR. “So much of the business model is insider information, and we think insider information is not always that useful.”

Public awareness of the current wave of data-based journalism can be largely traced to the rise of Silver, FiveThirtyEight’s founder and editor in chief. His roots in journalism trace to the statistical upheaval in baseball, which has revolutionized the way players are evaluated and even changed how the game is played. He began his journalism career by selling a statistic that forecasts a ballplayer’s future performance to Baseball Prospectus, and began writing for the site in 2003.

By 2008, Silver had shifted his attention to politics, starting the blog FiveThirtyEight.com in an effort to bring scientific analysis to political forecasting. His profile rose after he correctly predicted the winner in 49 out of 50 states during that year’s presidential election, and by 2010 he had relocated to The New York Times.

The Times prominently featured FiveThirtyEight, which takes its name from the total number of electors in the US electoral college. After Silver’s model nailed all 50 states in the 2012 Obama-Romney election, his fame exploded.

Despite the success of his blog at the Times, both in raising his standing and driving traffic, Silver left the newspaper in early 2013. Analyzing his departure, then-Times public editor Margaret Sullivan expressed admiration for Silver’s work, but said he caused dissension in the newsroom. “Much like the Brad Pitt character in the movie ‘Moneyball’ disrupted the old model of how to scout baseball players, Nate disrupted the traditional model of how to cover politics,” Sullivan wrote.

That disruption has spread across the industry, with newspapers, websites, and (perhaps less effectively) cable news embracing at least some level of data-driven reporting. When Silver relaunched FiveThirtyEight under the ESPN umbrella, Enten, then a 25-year-old columnist for The Guardian, was among his first hires.

Enten’s most distinctive feature is his voice. The nasally Bronx accent is reminiscent of something out of 1940s Hollywood, or what Ira Glass’s Jewish uncle might sound like.

Silver was drawn to Enten’s ability not just to cite statistics, but to ask questions about the numbers and take a skeptical approach to conventional analysis. “The standard to me is, even if you might not have an answer I agree with, are you worth reading?” Silver says. “Harry is always worth reading and worth listening to.”

As the election nears, more and more people have been reading and listening to what Enten and the rest of the FiveThirtyEight journalists think. According to data that ESPN provided to CJR, the site attracted nearly 10 million unique visitors last month, and the elections podcast was downloaded by almost eight million listeners over the same period. Enten’s rise, in an age of data primacy, mirrors the site’s.

Raised in Riverdale, the affluent, upper middle class neighborhood in the northwest corner of the Bronx, Enten claims that he first voted in a presidential election when he was four years old. His father, the former supervising judge of the Bronx Criminal Court, would take his young son into the voting booth for city, state, and national elections, and let Enten pull the voting lever.

These outings birthed an early interest in politics, that, combined with a fascination for prediction, led Enten to pursue a government degree with a specialization in statistics at Dartmouth. While in college, he interned at NBC News and Pollster.com, and started his own politics blog called “Margin of Error.”

In 2011, recently-graduated and jobless, Enten spent six months on his parents’ couch in the Bronx, blogging about the Republican primary race and getting drunk on espresso martinis with his father at a nearby bar.

He parlayed a freelance gig at The Guardian into a full-time position, writing about elections, weather, and sports for the website, where he adopted a relentlessly contrarian tone. “I pretty much discount the idea that Democratic strength among Latinos and young voters in 2012 comes close in any way to guaranteeing Democratic success in future elections,” Enten wrote in a 2013 piece. Although his assertion contradicted the prevailing wisdom, Enten backed it up with data from gubernatorial elections showing the success among Latinos of Republicans like New Jersey’s Chris Christie. It was this sort of analysis that won him a job at FiveThirtyEight.

On the podcast and in person, Enten’s most distinctive feature is his voice. The nasally Bronx accent is reminiscent of something out of 1940s Hollywood, or what Ira Glass’s Jewish uncle might sound like. When speaking on a topic he’s passionate about, Enten’s voice rises and he waves his hands for emphasis.

Getting ready for #SuperTuesday with @ForecasterEnten @FiveThirtyEight #DietInACan pic.twitter.com/S1TrpWtFl9

— Galen Druke (@galendruke) March 1, 2016

Whether writing or speaking, Enten is a font of historical minutiae. He made a point of weaving esoteric sports trivia or allusions to ‘90s sitcoms into nearly every conversation we had. It’s almost impossible to believe that he doesn’t spend most of his waking hours buried in reference books, but Enten claims to hate reading.

Instead, he draws on his prodigious memory or late-night binges of YouTubed election night clips and discontinued sitcoms, which he watches in his apartment a few blocks from FiveThirtyEight’s Upper West Side offices. Enten’s father, who he calls his best friend, died last fall, and aside from trips to the Bronx for dinner with his mother and Sunday afternoons watching football at the office, his time is entirely dedicated to his work. “I like what I do, and more than that, I live what I do,” Enten says. “I think very few people watch old election night clips on YouTube.”

To understand the facility of Enten’s memory, example works better than explanation. During a recent chat at the Manhattan diner, he recreated game four of the 1999 National League Championship Series (“It was on a Saturday. Jared Feldman was over to watch it.”); the 1977 New York mayoral race (“How can you get a better race than that one??”); and the television theme song discography of Jesse Frederick (“Perfect Strangers, Full House, Step-by-Step…did I say Perfect Strangers?”).

Neil Paine, a senior sportswriter at FiveThirtyEight and Enten’s deskmate for the past two years, remembers being impressed, confused, and somewhat unsure what to make of his colleague when they met. “I’d never in my life met a real person who is like this, talked like this, behaved like this, sounded like this,” Paine said. “I did not know that this type of person existed in real life.”

The data-driven, analytical nature of FiveThirtyEight’s journalism doesn’t leave much room for writing with personality. While Enten occasionally manages to hint at his interests (recently, he noted that some pollsters treat independent voters like the golden key in Super Mario World), the podcast and his lively Twitter feed best showcase his unique sensibilities.

Referring, on the podcast, to tightening post-Labor Day polls, Enten questioned whether Hillary Clinton was more like former Yankees closer John Wetteland or former Met Armando Benitez. On Twitter, he recently summed up his thoughts on the 2016 election thusly:

My thoughts on 2016. pic.twitter.com/zs67zC6DQY

— (((Harry Enten))) (@ForecasterEnten) September 12, 2016

Figuring out how to explain why this year’s race, and the coverage of it, is best represented by a dumpster fire has been among Enten’s goals for more than a year. As he sees it, 2016 has presented journalists with plenty of anomalies. Both candidates are historically disliked. Donald Trump, in his background and temperament, is unlike any candidate in memory. Endorsements from party leaders, which have played a large, sometimes decisive, role in past elections, seemed to have little influence on the Republican side of the primary. All this has created major problems for journalism. On Twitter, the dumpster fire .gif has emerged as visual shorthand for any sort of complete disaster. For Enten and many others following this election, the metaphor is clear-cut.

While the data journalism community has wrestled with this trash-fueled blaze, critics have been happy to point to this year’s upheaval and lump the failures of forecasters together with other faults they see in journalists practicing this brand of analysis. At times, Silver and others in the field have come off as smug, and Trump’s success has certainly been a rebuff to the prognosticators who promised he would fade numerous times over the past year. But more than that, the sample size for presidential elections under the current model is small. Demographic data and voting preferences are constantly shifting, and with elections occurring only every four years, making predictions is extremely challenging. Still, the accurate analysis of the available data is vital both to the public and to politicians.

FiveThirtyEight podcast guru Jody Avirgan acknowledges the value of talking to voters and looking at yard signs. But he likens his employer to a media criticism site whose job is “to butt up against the conventional wisdom, the unsubstantiated reporting, the rumor-mongering, chasing the latest shiny thing. Frankly if there weren’t bullshit news cycles to butt up against, I don’t think we’d have as prominent of a role.”

Nate Cohn, one of Silver’s successors at The New York Times, says that getting statistical analysis right is vital not just for making predictions, but for providing a framework for political change. “Bad data analysis and bad polling has had an effect on our democracy,” says Cohn, who is an admirer and friend of Enten’s. “The country is undergoing big changes demographically, politically, culturally, and I think that the way that those changes are interpreted and perceived by the public is, whether people realize it or not, a big product of the available data.”

The reality for political reporting, as nearly every journalist CJR spoke to for this story made clear, is that the distinction between “traditional” and “data-driven” journalism is a bit blurrier than the binary narrative often cited by critics of data journalism. “I think it is well worth the time to talk to voters to get interviews, tell a story like that, go to campaign stops. I think that’s a very interesting part of politics and elections,” Enten says. “But I think that numbers themselves are a story in that you’re talking to hundreds–and then when you’re combining polls–thousands of voters.”

Yet even Enten acknowledges that sometimes “the numbers tell you something, but you need to talk with people to understand it.” He points to a recent piece about young voters’ lack of enthusiasm for Hillary Clinton in which he looked at polling data broken down by generation and found that the margin by which a demographic approved or disapproved of Barack Obama’s presidency aligned closely with whether that group supported Clinton or Trump. Only one set of voters went against the grain: People between the ages of 18 and 24 held Obama in high regard, but were far less likely to say they supported Clinton.

This article, and the data from which it was drawn, have impacted both Clinton’s strategy and reporting on the topic. Enten called it “a perfect case where numbers can lead you to something, and then you can go out and use traditional reporting and figure out why that is, what is going on.”

With less than 50 days until the election and three debates on the horizon, the deluge of media attention will undoubtedly make it more difficult to distinguish what is actually going on in this race, what really matters and what’s just noise. While plenty of outlets will provide valuable reporting on campaign strategy and insider opinions, Enten will be at his computer analyzing the data, trying to explain its meaning, and following the numbers where they lead.

Pete Vernon is a former CJR staff writer. Follow him on Twitter @ByPeteVernon.