Michael Sitrick will be your best friend and your worst enemy. Michael Sitrick notices when you got a fact wrong in your story. He won’t yell at you, though. He’s good that way. Michael Sitrick always takes your questions and you can just call him Mike. Mike is easy to love and easier to fear. And he heads one of the most expensive PR firms in the business, with a rate reported to be $1,100 an hour.

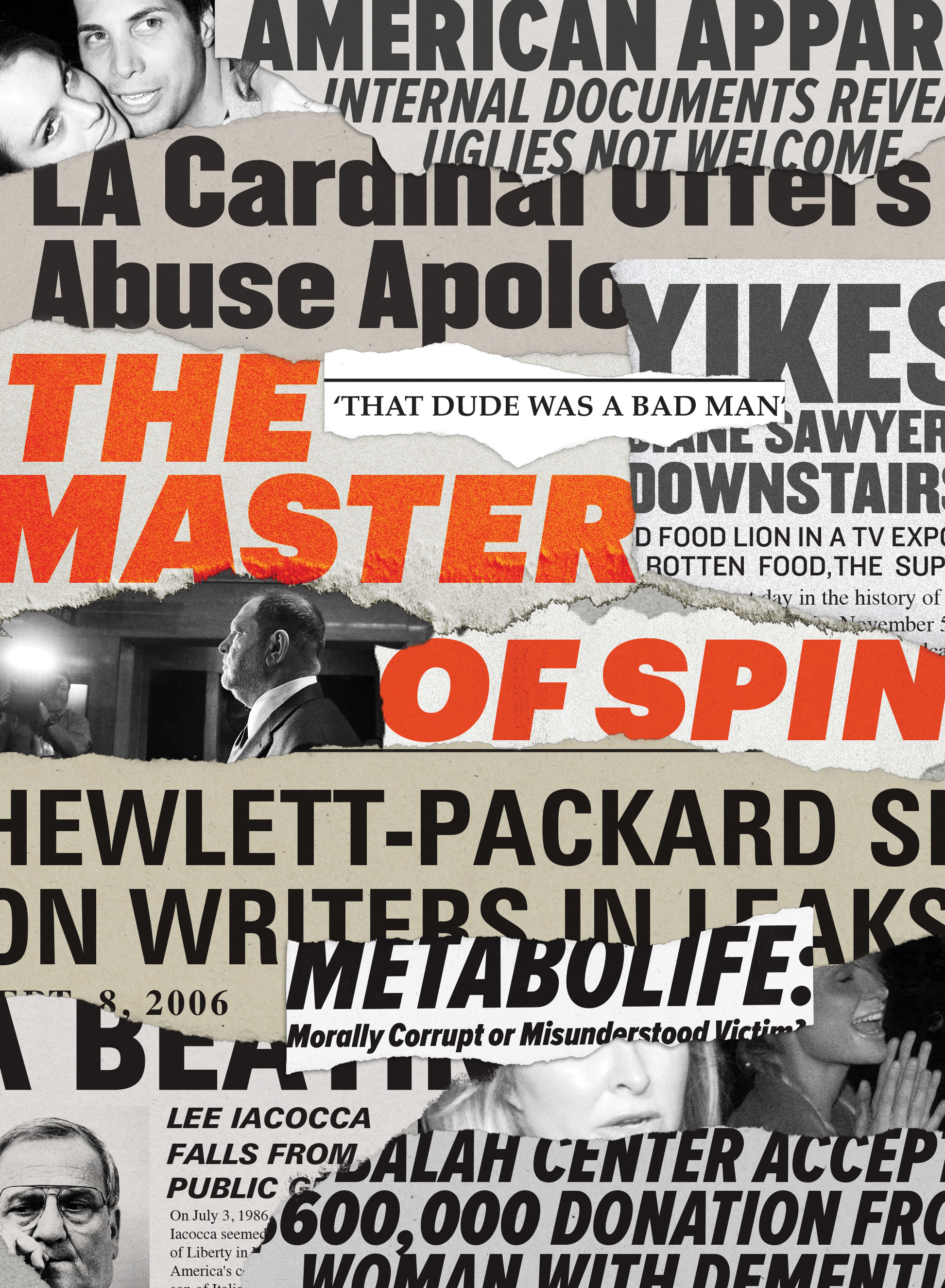

Michael Sitrick, 71, is a public relations puppet master who has pulled the strings behind some of the biggest stories in media. He specializes in crisis PR and has made a name for himself as the man you call when you have money and step in some shit. Clients in that category have included Roy Disney during the ouster of Michael Eisner as CEO of the entertainment company; Food Lion, a grocery chain, during its fight against an ABC report about unsafe food-handling practices; Metabolife, accused of lying to the Food and Drug Administration about how ephedra can kill you; Patricia Dunn, during the Hewlett-Packard spying scandal; Lee Iacocca, during his life as Lee Iacocca; the Los Angeles Catholic archdiocese during the abuse cover-up scandal; American Apparel when it cut ties with creepy founder Dov Charney; R. Kelly, although not recently; and Harvey Weinstein.

ICYMI: BuzzFeed reporter discusses controversial scoop

And he has done all that without uttering what is usually considered a lie, which of course depends on your definition of a fact. And your definition of the truth. And the definition of a lie. Which is why talking with Michael Sitrick is a confusing game. That’s why he’s good. That’s why he’s scary. And that is why he’s the perfect mirror to a media industry in crisis. Sitrick hewed the contrarian take when Slate was just a twinkle in Michael Kinsley’s eye. Sitrick was using the internet and social networks to stoke distrust in the media when Donald Trump was still hosting WrestleMania. Seeing journalism through the eyes of someone so good at manipulating it might offer us a window into understanding what’s gone so wrong. Or maybe it offers us nothing; maybe he was just spinning me, too.

Illustration by Esther Wu

Ryan Holiday, the former PR person for Tucker Max, who wrote a whole book about lying to the media, calls Sitrick the greatest public relations operator of all time. Holiday, who worked with American Apparel at the time the company hired Sitrick, compares him to the original PR master, Edward Bernays, famous for promoting cigarettes as feminist “freedom torches.” Holiday tells me, “Like Bernays, he has also had his share of controversial clients. That’s one of the pitfalls of success in that business—the better you get at it, particularly in the crisis game, the more unsavory people need your services.”

Sitrick courts the unsavory. He thrives on the fight. He is fond of telling apocryphal, though possibly at least partially true, stories about fighting bullies on the South Side of Chicago, where he grew up. In one tale, Sitrick’s younger brother David is beaten up by five kids on the way home from school. Sitrick’s father tells him, “You do what it takes to make sure this never happens again. . .He’s your brother. Fix it.” Sitrick does. He and David go back and square off against the bullies and prevail.

There is another version of the story, one that appears in a 2006 Los Angeles magazine profile of Sitrick. In this telling, his father instructs him to let David fight a bully himself, but to go along with his brother to make sure the “fight is fair.” The story is the kind that journalists love. The moral that Sitrick wants us to learn is that he is the champion of the little guy. The fixer. The man who ensures a fair fight. But a bully is a bully because he has power. How can a fight ever be fair when the price is $1,100 an hour?

Maybe the real moral is that Sitrick just loves a tough fight.

Sitrick is the oldest of three boys, born in Davenport, Iowa, to Marcia and Herman. They moved to Chicago when he was three months old. When I speak with him, Sitrick makes a point of saying that he grew up in a one-bedroom home on the South Side. His dad, a decorated World War II vet, was the general sales manager for WGN Radio. The family moved to Alabama when Sitrick was in his senior year of high school. But Midwestern grit and the grift of Chicago are what made him. He’s animated when he talks; his voice still has a little of that Chicago grind in it. He knows how to tell a good story. And the stories he tells are of fights, first his father’s, and then his own.

His father, he says, single-handedly captured 21 Nazis during the Battle of the Bulge. It sounds improbable, but Sitrick doesn’t lie, that’s one of his rules: don’t lie and always back up your claims. The story goes like this: during the battle, Herman captured the German soldiers one at a time as they came into an abandoned farmhouse seeking shelter from the cold. In 2017 he was awarded the Legion of Honor, France’s highest distinction for military and civil actions. He died in January at the age of 93.

According to Sitrick, he’s no less brave. At 15, he was jumped by five kids from his parochial school, who pushed him down the stairs. He recalls being knifed beneath a viaduct. Who knows which parts of these stories are actually true, but they’re almost too good not to print—and of course, they’re repeated in nearly every profile of him. Hell, they make great copy. Sitrick knows what reporters love.

Another story Sitrick likes to tell is of his fight with his parents when he tried to drop out of college to become a professional musician, playing guitar and singing in a band with his brother. He was offered a recording contract when he was 18, but was told he’d have to go on tour. According to Sitrick, his mother told him, “You’ll go on tour, but it will be Vietnam!” He didn’t drop out of school.

He worked briefly as a reporter, but bailed when he found he could make more money in PR. He worked for Mayor Richard Daley’s Department of Human Services, where he insists he was not involved with any of the scandals that office generated. He went on to Selz, Seabolt & Associates, the National Can Corporation, and Wickes.

But it was media that made Sitrick. In 1985, Sitrick orchestrated a Wall Street Journal article on Wickes, a failing retail giant, describing how, after it had been devastated by the recession of the 1980s and come under investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission for omitting information from tax filings, it had emerged triumphant from a Chapter 11 bankruptcy. The story was a risk. Sitrick gave a journalist named Stephen J. Sansweet unrestricted access to the company. In exchange, Sansweet agreed not to write about anything sensitive until Wickes was reorganized. Sansweet did not return CJR’s requests for comment, but in 2006 he told Los Angeles that he had smoothed Sitrick’s way into the world of media. “I must have made half a dozen calls on Mike’s behalf to Journal reporters and bureau chiefs around the country. I’d say. . . ‘I think you can trust him.’ ”

The Journal article is typical of what has become Sitrick’s style of spin: It’s long, written by a reporter with cachet, and it preempts the story of the bankruptcy, depicting the new CEO, Sanford Sigoloff, as tough and hardworking. It’s not fluff, but it’s not negative, and, most important, Sitrick’s name doesn’t appear in the article at all.

Not long after the Wickes article, Sitrick got a call from Roy Disney and Stanley Gold. Gold ran Disney’s investment company, which was trying to acquire Polaroid. Disney was being labeled “Roy the Raider” in the press and wanted Sitrick’s help reassuring the public that Polaroid would not be cut up and sold for parts. Sitrick took the job, and in 1989 Sitrick and Company was born.

ICYMI: Poll: 60% of people think journalists get paid by their sources

His favorite fight was the one starring Hewlett-Packard and Patricia Dunn, whom Sitrick calls Pattie. Dunn, chairwoman of the board at HP, hired a security firm to investigate leaks at the company. That security firm hired private investigators, who impersonated members of the press in order to access phone records for HP executives suspected in the leaks. Dunn was indicted on felony charges for the illegal spying. (The case came years before Weinstein, another Sitrick client, used similar tactics to attempt to bully reporters.) Sitrick maintains that Dunn was a scapegoat, that everyone at HP knew about the spying, that it wasn’t her fault. He had her go on 60 Minutes, an op-ed with her byline was published in the Journal, and James Stewart, a business writer, produced a fairly sympathetic profile of Dunn for The New Yorker. The charges were dismissed. Pattie had been wronged. Did you know she had cancer? She was being bullied. He fought for her and won.

Or that’s the truth as Sitrick sees it. The house of cards he helped stack. The other version of the story is that Dunn was a control freak who oversaw an illegal spying operation run amok, who got off because of her failing health. Each story has the same elements—but if stacked differently, they can offer different scenarios. Which one do you want to believe? That’s how Sitrick fucks with you.

The stories Sitrick builds don’t always last. Sitrick was hired to represent Metabolife, the multilevel marketing company that sold ephedra-based weight loss supplements. The company came under fire when the supplements were linked to thousands of heart attacks, strokes, and deaths. The founder, Michael Ellis, was charged with lying to the FDA. Sitrick fought hard against the negative public perception of Metabolife. In The Fixer (2018), written with Dennis Kneale, he talks about how he allowed Ellis to be interviewed on camera but only in a gym crowded with Metabolife employees, because he didn’t trust 20/20. (Sitrick also insisted that the interview be streamed live online.) Sitrick argues that the FDA was out to get Metabolife and to expand its turf by regulating diet pills.

Despite the PR efforts, Ellis went to jail. When he came out, he wrote a book that insisted on his innocence. In his own book, Sitrick writes, “Independent studies proved that his product was safe and effective when used as directed. And millions and millions of people had used the product over many, many years without incident.”

The other version: ephedra was a dangerous supplement and Ellis knew it and hid its effects. The government took action and banned ephedra. Ellis was convicted of lying to the FDA.

The Sitrick story is Trumpian in its use of facts that are not facts, its theme of distrust of the media, and the character of the aggrieved who is unfairly targeted by the government. Or as Sitrick and Kneale outline the approach in The Fixer: get the facts, act preemptively, use social media as a means to an end, and put your opponent in the wheel of pain.

The wheel of pain, it seems, involves hammering the press on the facts until the story is changed or killed. In the Food Lion case, Sitrick was brought in to represent the company as it was suing ABC for a Primetime Live special about unsanitary food-handling practices. Food Lion argued that ABC had committed fraud by sending reporters into the stores posing as Food Lion employees. In 1997, a North Carolina court found the network guilty of trespassing and fraud. Sitrick had PR representatives in front of the courthouse every day, spinning what had happened inside to the media. The matter at stake—as Sitrick tells it in Spin (1998), written with Allan Mayer—wasn’t “investigative journalism, it was honesty in journalism.” But the truth was, Food Lion was selling rotten meat. Food Lion won in 1997. But in 2002, a court overturned the verdict.

When I ask if he regrets his role in any of these stories (including that of Weinstein, who was later dropped as a client), Sitrick doesn’t answer. Instead, he focuses on the injustice committed, the supposed wrong he was hired to right. That time he was brought on to represent the Archdiocese of Los Angeles? It wasn’t the molesting priest he was defending, but the good name of the church. “You have to look at what the objective is,” he says. “When you’re brought in, and what you see, when you see it. For example, in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, we’re representing the church, not the priests.”

His words are offered as a defense that’s not really a defense. He gives an answer, but it’s also not an answer. He deflects from the big-picture wrong to the specifics. The method positions Sitrick as a defender not of history’s assholes, but of truth.

“We try to find out what the information is,” Sitrick tells me. “If it’s wrong, we want them to correct it, and most journalists want it corrected.”

Which seems innocuous enough. But once you pan out on his logic, you realize he’s still rehabbing the reputation of a church that harbored and excused abusers for years.

“If somebody is a bad man, or a bad woman,” Sitrick argues, “you still have an obligation, I believe. . .to give their side. At least, to withhold judgment until you hear their side.”

It’s a sentiment that seems, on the surface, objective. But it presupposes that Sitrick’s clients, the wealthy and powerful, haven’t been controlling the story from the beginning. It’s a false equivalence of power. It’s spin.

Still, Sitrick argues that everyone deserves a good defense, even—maybe especially—if the court of public opinion has turned against them. The media can be an angry mob. Social media can be even worse. Misinformation can derail someone’s life.

In this, Sitrick isn’t entirely wrong. The question is his method, and who is entitled to this good and costly defense.

I ask Sitrick if there is someone so bad he won’t defend them.

“The American Nazi Party, of course not,” he says.

“What about Richard Spencer?”

“I don’t want to talk about specifics,” he tells me. “But if you are talking about Harvey Weinstein—.” He launches into a story about getting the call to represent Weinstein on the day his own mother died. He focuses on that story. It’s detailed. I get the name of the restaurant he was at with his father when the nurse called with the news. What he said to the nurse. As for Weinstein, I get one sentence. Sitrick agreed to represent him and a few months later dropped him. Why? “It’s a client confidence matter,” he says.

It’s brilliant spin. I can’t think of him as a Weinstein-defending monster when he’s telling me a story about the death of his mother, can I?

Sitrick tells me about a client, no name given, who was facing a rape allegation. The client showed Sitrick texts from the woman indicating that the sex was consensual. Confronted with the texts, the woman admitted to making the charge up. Done. Wrong made right.

But what if it wasn’t made up, I ask? Women often text their eventual rapist, who often starts out as a friend or lover. Women are afraid to go forward with a rape charge.

She lied. He protected a young man’s life and career.

But what if he didn’t? I push.

Sitrick is calm and self-assured: the facts are there. The facts support him. He’s not here to debate what-ifs. “In this case she lied,” he says. “In this case she admitted it.” I drop it. He spun me. I know he spun me. He spun me the whole interview. But how can I argue? He is so confident. He seems to know the truth, while I’m just looking for it.

But facts are hardly neutral. How the cards are stacked determines the outcome of the game. In the words of a former ABC employee with extensive knowledge of the Food Lion case, Sitrick’s PR work was “fake news before fake news existed.”

It would be easy to call the PR work of Sitrick evil and journalists the prevailing warriors for truth. But it’s not so simple.

Sitrick doesn’t see what he does as dishonest; nor does he see the media as the enemy. Sitrick is careful; he doesn’t dislike the media. He understands they/we are underpaid and overworked. We’re all competing for scoops and now, with the internet, it’s hard. He gets it. He hires journalists. He just wants us to understand “the truth.”

Sitrick’s favorite tactic is one he calls “lead steer.” The idea is that you find a journalist who is respected and you give her a story that counters the accepted narrative about your client. Journalists want a scoop. And where one journalist goes, others will follow.

Sitrick isn’t wrong. That’s the problem. The reality is, contrarian hot takes are the bread and butter of online journalism. Entire media companies like Gawker were founded on them. But at the heart of the metaphor is that journalists are cattle. After all, as every cowboy knows, one of the ways to end a stampede is to ride to the front of the herd and lead the livestock where you want them to go.

The stampede rushes forth. As a journalist, reading Sitrick’s ideas about PR and media is like looking at yourself in a funhouse mirror—it’s you, but warped. They aren’t bad rules, either. “Never lie” is a good one, although lie seems to be a matter of spin. The rule that “no comment” can be “PR malpractice” is another that seems okay to me, as a reporter. But access journalism often comes at a cost to objectivity. Where is the line? It’s easy to see why the moral compass of a journalist might get skewed by his magnetic force.

In Spin, Sitrick explains that journalists see themselves as “the countervailing force that keeps the oligarchs and plutocrats at bay. And if in the process a reporter can manage to make a name for himself—respected by his peers and honored by the Pulitzer committee—who’s to say that’s such a bad thing.” It’s a line that cuts journalists to their core. A not inaccurate profile, but one that feels dismissive, declaring us social justice warriors, motivated by an underdog. He understands us better, perhaps, than we understand ourselves. Like I said, Sitrick fucks with you.

So he woos journalists. He’s kind to them. He answers their calls, before deadline. He makes his clients available. He gives facts. He gives stories. He’s likable and charming and good at what he does. If writing is like building, arranging the information so that it stands, Sitrick not only blows the house down, he rebuilds it for you. During the reporting of this story, Sitrick was kind and generous. He offered a list of journalists and employees who would answer any of my questions, and they all did. They all spoke glowingly of Sitrick. He also did research on me. He read my articles. He knew about my divorce; he empathized with me. He said, “I think your ex was a jerk.”

I was mad when he said this. It felt manipulative. But I was also flattered: he did more research on me than the last four guys I dated. I think he meant it. It felt like he meant it. Or maybe I just got spun. Maybe both can be true.

If so, Sitrick is the paragon of the present moment. He truly believes what he’s selling. He truly believes the media got ephedra wrong. He truly believes we got Food Lion and Patricia Dunn wrong.

And that’s the thing: it’s not really about spin, but about belief in what truth is, what justice is. About how two people can look at the same facts and walk away with different stories. But if journalists are seekers, Sitrick is the guru. He believes he knows, while we are merely looking, and it’s that seeking that makes us malleable. He knows we are malleable. We want to get it right. So if he can sow doubt, with something that looks like proof, well, then? He has an in. And it’s hard to trust the story that you know is right when someone is telling you you are wrong. If it were a relationship, we’d call it gaslighting, but it’s a profession, so we call it PR.

Also, Sitrick’s touch is so light. Seth Lubove, a former Bloomberg News journalist who now works for Sitrick, says that he’s heard him yell in the office, but never at a reporter. In The Fixer, Sitrick notes that punching back at reporters is never a good idea. You have to be nice, and when you do fight back, you fight back with information and with the wheel of pain—relentlessly demanding the facts. Often he treads so carefully, journalists barely know he was there. Even those who were railroaded by him never knew his name until afterward. This is often because Sitrick isn’t hired by his clients themselves, but by their lawyers. Sitrick then directs the operation under the aegis of attorney-client privilege.

And he’s not always wrong. In the HP case, Pattie Dunn was being hung out to dry; surely other executives were equally guilty of doing what she did. With Metabolife, sure, maybe some people used it and didn’t die.

It would be easy to call the PR work of Sitrick evil and journalists the prevailing warriors for truth. But it’s not so simple. The reality is, he’s right. Media does mob. Journalists do get sloppy. Journalists can be evil. PR reps can fight bullies. The news is sometimes fake. The spin is sometimes right. Truth and fiction are contained in both occupations. Michael Sitrick will fuck with your moral compass. But then again, so will journalism.

UPDATE: This story has been updated to reflect that reporters entered the courtroom of the Food Lion trial.

ICYMI: How Esquire lost a major expose to The Atlantic

Lyz Lenz is a writer based in Iowa. Her writing has appeared in Pacific Standard, Marie Claire, Jezebel, and the Washington Post. Follow her on Twitter @lyzl.