In early August 1852, the Sacramento Daily Union published a story headlined “Fatal Duel—Death of the Hon. E. Gilbert.” The article appeared on page two. That a duel did not merit front page treatment is hardly surprising. Newspaper front pages in the mid-19th century were dominated by advertisements for butter, lamp oil, and tooth repair. As news, a duel—even a fatal one—was hardly novel. Back then, if two men were having a dispute it was customary to settle it in an open field, standing back-to-back, then walking an agreed upon number of paces before turning and opening fire.

What does seem novel about this particular duel are the participants: James W. Denver, a decorated war general, and Edward Gilbert, editor of the weekly Alta California who despised corruption. How did these two wind up in a death match? The Daily Union, in reporting “the deplorable termination of a duel,” didn’t shed much light, taking a too-soon approach in describing the dispute. “This is not the time or place to speak,” the paper wrote. “The community has lost a gentlemanly and honorable member.”

ICYMI: A school district kept a secret blacklist for decades. A reporter found it.

What happened, it turns out, is what happens every day in journalism: The subject of an article did not like how a piece turned out. Denver took issue with how Gilbert had reported the general’s efforts to aid starving and downtrodden immigrants in Carson Valley. “The article charged Gen. Denver with negligence and gross mismanagement in the distribution of provisions,” according to the California Newspaper Hall of Fame, describing how “some of the supplies were sold to Denver’s subordinates who pocketed the receipts.” To Denver, this was blasphemy.

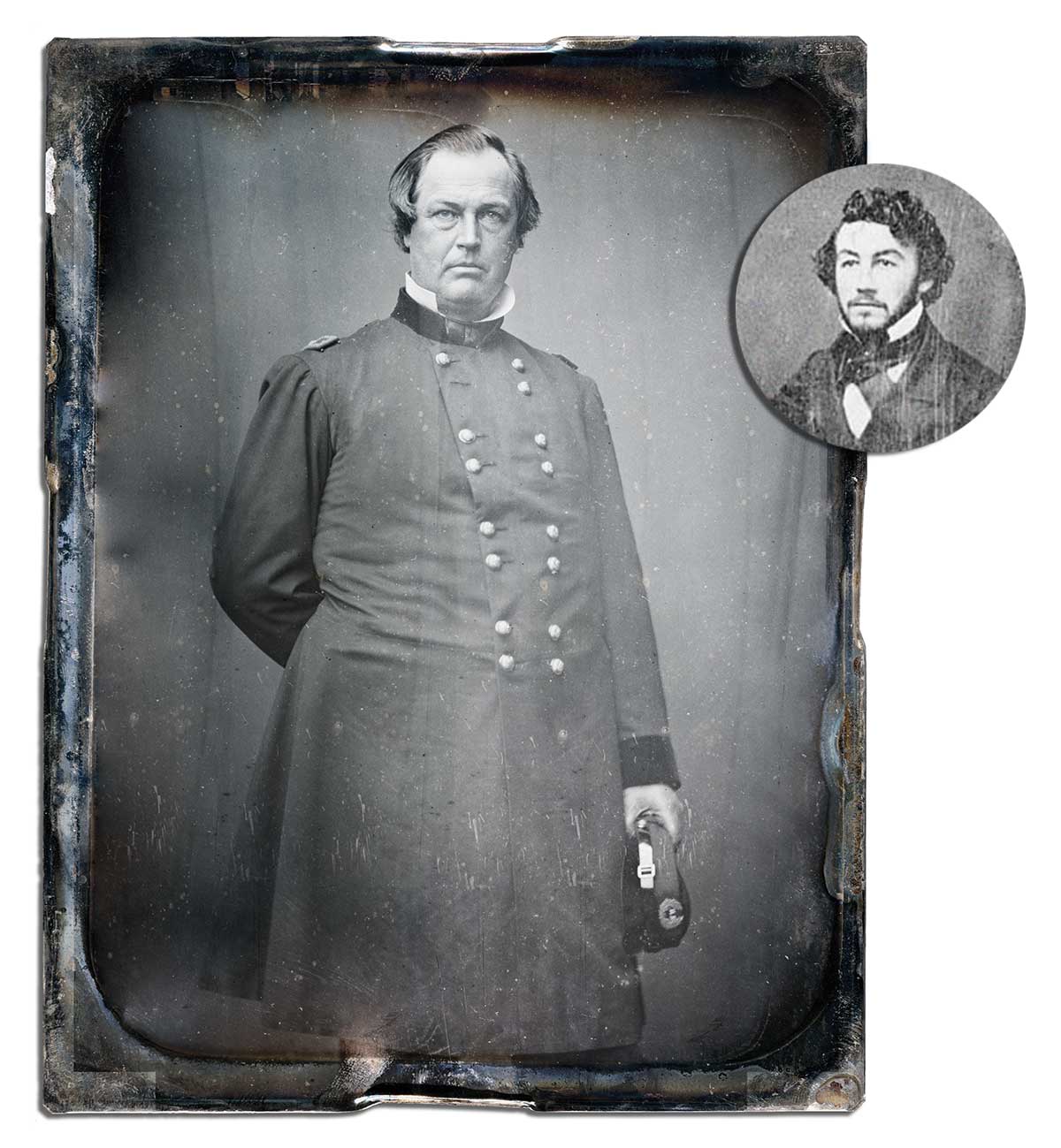

Gen. James W. Denver shot newspaper editor Edward Gilbert (inset) in a duel in 1852 that left the journalist dead. In the mid-19th century, settling scores by death match was hardly unique.

So the two men resolved to settle the matter with honor, agreeing to meet at a lush field called Oak Grove. They arrived at sunrise. “The weapons selected were Wesson’s rifles,” the Daily Union reported, “and the distance forty paces.” Gilbert was clumsy. He was not a good shot. Denver had been a soldier. Perhaps the old general felt bad for his rival because after they stepped 40 paces, Denver shot but badly missed Gilbert. To the gathered crowd, this looked intentional. Gilbert missed, too. Technically, the men could have parted ways. But Gilbert insisted they go again. “Denver then became angry,” the Hall of Fame account continued, “and muttered something about not going to stand around all day being shot at.”

They reloaded, then stepped off 40 paces again. “Mr. Gilbert fell almost instantly,” the Daily Union reported, “having received the shot of Gen. Denver in the left side just above the hip bone.” Gilbert didn’t move. “Four or five minutes after the occurrence, and without a word or scarcely a groan, his spirit passed from the earth,” the Daily Union said. “Many a manly tear was shed.”

In Gilbert’s time, and for many decades afterwards, physical attacks on the press weren’t just acceptable, they were expected.

No doubt these are dangerous times for reporters. Donald Trump has declared war on the media. Supporters at his rallies scold and threaten reporters, in person and through T-shirt slogans. (“Rope. Tree. Journalist,” one shirt reads. “Some assembly required.”) And while much of the chatter amounts to empty threats from trolls, there has been violence. In 2016, a Trump campaign staffer grabbed a female reporter’s arm so tightly that she was bruised. Last year, Montana congressional candidate Greg Gianforte body-slammed a Guardian reporter during tough questioning, an attack the Committee to Protect Journalists said “sends an unacceptable signal that physical assault is an appropriate response to unwanted questioning.”

At least no one whipped out a gun. In Gilbert’s time, and for many decades afterwards, physical attacks on the press weren’t just acceptable, they were expected. Gilbert’s killer was not arrested. In fact, not long after shooting the editor, Denver was appointed Secretary of State in California. The city of Denver was named after him. “The mid-nineteenth-century California community did not see anything abnormal in the circumstances surrounding Gilbert’s demise,” writes historian Ryan Chamberlain in his book, Pistols, Politics and the Press.

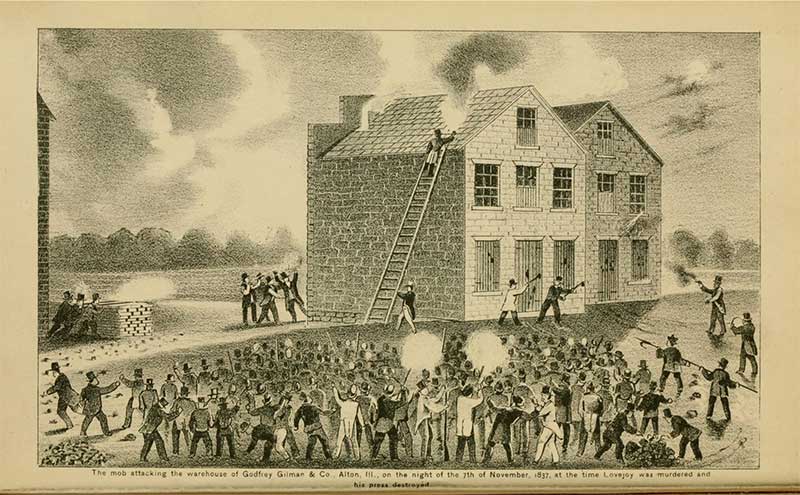

A pro-slavery riot in Alton, Illinois, in 1837 resulted in the murder of abolitionist newspaper editor Elijah Lovejoy.

It is a point worth reflecting on in our chaotic, mean-spirited moment that the First Amendment has never been a magical forcefield protecting the press, even from violence. Besides duels, journalists over the years have been attacked by angry mobs, kidnapped, beaten, even tarred and feathered. Their homes were egged, presses set on fire, horses stolen. Covering Congress was at times so hazardous that in addition to pencils and notebooks, some reporters carried daggers. The violence wasn’t just between journalists and those who didn’t like their reporting. Reporters and editors used to fight—even duel—among themselves. (Some still do; see Twitter.)

It may be comforting to know that times have actually been worse for journalists. But re-examining past attacks is also instructive, historians say, because the political, social, and journalistic forces that sparked violence against reporters in the country’s early days can resemble the disputes of today. Battles over class, immigration, and the country’s place in the world get at the core principles of America. News sites like Breitbart News and HuffPost are akin to the 19th-century partisan press. And social media acts as kindling just as the telegraph did a century ago, quickly and widely spreading controversy.

ICYMI: A newsroom was told by management to run a “vile” editorial. Staffers made a bold move.

“In a sense, people say that the current media situation is reminiscent of the highly partisan journalism of the 19th century,” says John Nerone, a University of Illinois journalism professor. “And what you see reappearing are some of the forms of violence associated with that 19th-century journalism.”

Nerone, in his book Violence Against the Press: Policing the Public Sphere in U.S. History, writes that physical attacks on the press have been “common enough to become part of the mythology of US journalism.” Mark Twain, in “Journalism in Tennessee,” one of his less well-known short stories, describes errant shots being fired at the editor of a fictional paper called the Morning Glory and Johnson County War-Whoop. The editor returns fire, then goes back to work. A short time later, a grenade is dropped down the newsroom stovepipe. “The explosion shivered the stove into a thousand fragments,” the narrator says. “However, it did no further damage, except that a vagrant piece knocked a couple of my teeth out.”

Satire, of course, only works if the details are plausible. “The hyperbolic violence that characterizes the daily routine of the chief editor of the War-Whoop is funny,” Nerone writes, “because it is an exaggeration of the familiar. Nineteenth-century editors were expected to counter violence.”

Physical attacks on the press have been “common enough to become part of the mythology of US journalism.”

Before Twain, around the time of the American Revolution, newspapers served the function of a town meeting. “The purpose of the paper was to allow citizens irrespective of class or party to communicate freely and deliberate rationally,” Nerone writes. Of course, not all opinions were equally valued by all parties, particularly those with any whiff of support for the British. Publishers and printers let authors write anonymously—often under silly pseudonyms—to encourage lively debate, which sold more papers. (This is somewhat analogous to today’s reporters granting anonymity to let sources “speak freely” on controversial topics.)

Those impugned in print were prone to violent retaliation, if they could get the author’s name. This often put printers on the wrong end of a club. Nerone writes of William Goddard, the forgotten newspaperman who ran the Pennsylvania Chronicle, along with a less forgettable character of history—Benjamin Franklin. In 1767, the paper ran a letter signed by “Lex Talionis,” Latin for retaliation. The target of this letter, a Mr. Hicks, approached Goddard a few days later at a tavern, but Goddard wouldn’t give up Lex’s identity.

“I was immediately surrounded by a number of persons unknown to me, with Mr. Hicks at their head, who became grossly abusive, and treated me with great insolence,” Goddard wrote in his own paper. “He repeated the designs he had formed to break my bones, and that he had prepared a suitable weapon for his purpose.” Hicks walked away. Goddard thought it was over and he went on drinking. But it was not. A friend of Hicks approached him to express his own displeasure with the letter, ordering him to leave. “I told him I had as much business there as himself,” Goddard wrote, “and refused to be turn’d out of doors. Without further ceremony, he struck me.”

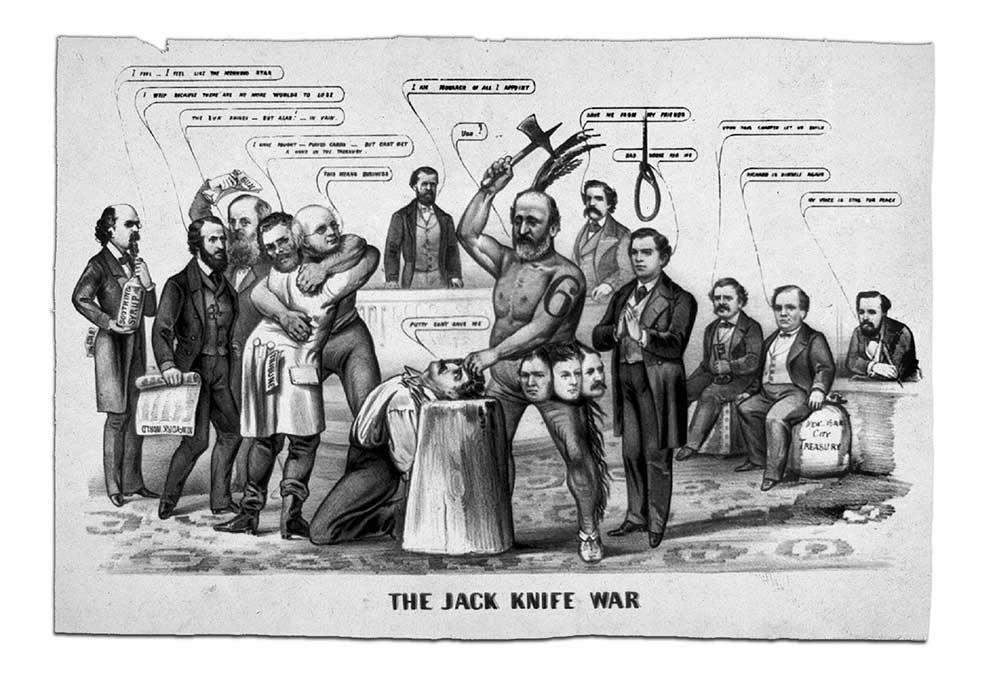

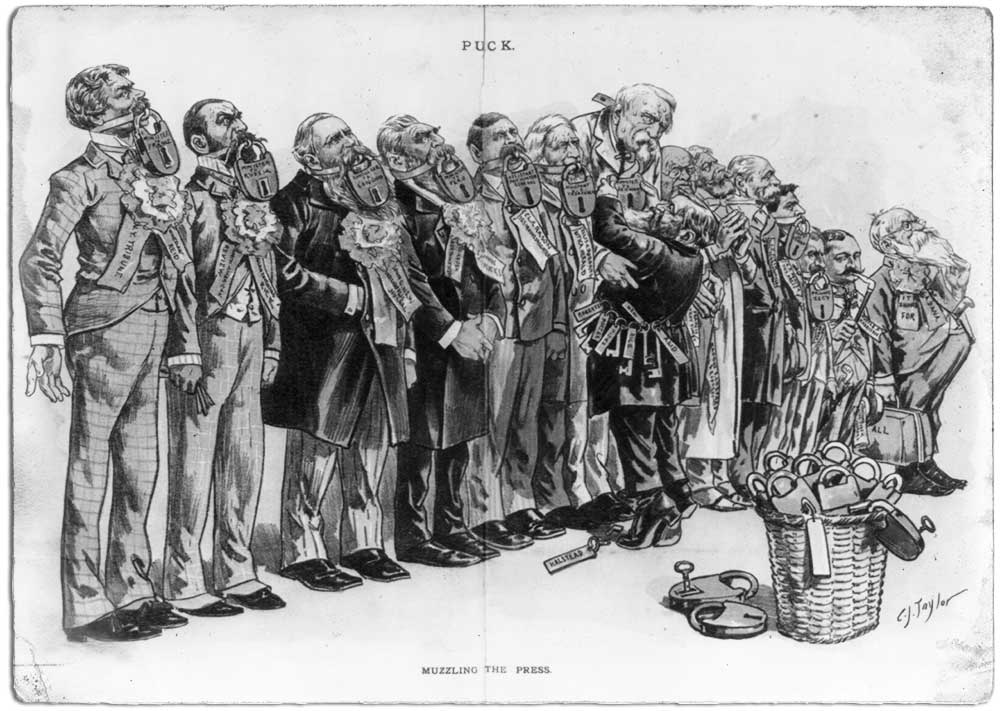

Political cartoons routinely depicted the muzzling, or worse, of journalists. Here’s an example with “Boss” Tweed in New York City in 1870.

Such attacks were daily events, as reliable as early-morning Trump tweets. They persisted in part because there was no discernible infrastructure—social or governmental—to prevent them. If a man was wronged or publicly insulted, he was obligated, out of a sense of honor, to retaliate. “It would be hard to overstate the importance of personal honor to an eighteenth-century gentleman,” Yale historian Joanne B. Freeman writes in Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic. “Honor was the core of a man’s identity, his sense of self, his manhood. A man without honor was no man at all.”

Violence against the press escalated both in frequency and viciousness as the stakes increased, particularly during the Civil War, and Reconstruction. The press had First Amendment rights, but this was before the honor culture abated and court rulings solidified the press freedoms in place today. “Freedom was understood as a middle ground between tyranny (no freedom) and licentiousness (too much freedom),” Nerone writes in a 1998 collection of scholarly essays.

Anti-abolitionists were particularly dangerous. Nerone cataloged more than 100 mob attacks against papers that supported abolishing slavery, the most infamous of which was the attack on Elijah Lovejoy in 1837. The minister-turned-newspaper man was killed in a gun battle with anti-abolitionists. At the Newseum in Washington, DC, on a memorial to slain journalists, Lovejoy’s name is listed first. There were dozens of other less high-profile attacks. Newspaper buildings were set on fire. Editors were egged and attacked physically by ideological opponents, as well as in print by other papers. A 1987 scholarly paper that analyzed coverage of attacks against abolitionist newspapers found that “the papers with the most demonstrable ties to established parties ignored freedom of the press issues and fervently blamed and opposed the abolitionist editors.”

During the Civil War, more than a hundred papers in the north were mobbed, egged, or set on fire. The attacks were led either officially or unofficially by Union troops upset over criticism of battlefield strategy, anger at any sign of sympathy for the South, or out of fear that reporters were disclosing too much information about internal politics and decision-making. General William Tecumseh Sherman held the most extreme hatred toward the press. “Napoleon himself,” he once said, “would have been defeated with a free press.” Nerone fact-checked Sherman’s bold assertion in a rather hilarious footnote: “Oddly, Napoleon was defeated without a free press.”

Journalists didn’t fold easily. If their presses were burned, they didn’t walk away—they would find other printers, open new newsrooms, and go right back to reporting the news. They also found clever ways of dealing with bullies, particularly those in government who threatened them with violence. A classic example is how two reporters from the Congressional Globe dealt with Representative Waddy Thompson of South Carolina.

Thompson was a real rascal. He owned slave plantations and opposed just about everything in the North. Thompson also had a temper and the physical capacity to intimidate. One account described him like this: “Thompson, whose physique was alarming, and whose spirit was thought to be like that of fiery hotspur.” In the winter of 1839, Thompson become upset with Globe reporters Lund Washington, Jr. and William W. Curran. According to an account in the annual report of the National Shorthand Reporters’ Association, the reporters “had failed to give him a larger space in the proceedings than his calibre merited.” Thompson’s recourse: “He made a tongue attack upon them in the House, and was prepared to attack them with arms elsewhere.”

Political cartoons routinely depicted the muzzling, or worse, of journalists. Here’s an example with President Benjamin Harrison in 1889.

The reporters armed themselves for self-defense. “Mr. Washington, a gentleman of much strength, carried with him a heavy bludgeon into the reporter’s box,” the shorthand association account said. “Mr. Curran was provided with a dagger or knife, sharpened especially for use.” Nobody came to blows. Though the reporters were prepared to stab and beat the congressman, they settled on a more passive-aggressive response. “No matter what Waddy Thompson said in debate, the reporters made no note of it,” according to the association. “They treated him as a blank. This brought the South Carolinian to terms. He made an open apology to the reporters, with the effect of restoring peace.” The power of the press, at least back then, included the power to make an egotistical nitwit disappear.

Still, violent attacks continued well into the Civil War. But in many ways, the war’s end also marked the end of routine violence against the press. For one, the war brought stable governments to many cities and towns, with laws, policing, and town halls that normalized sensible, non–violent political debate. Also, according to Nerone, the ensuing years gave rise to a more professional press, particularly as industrialization took hold. Newspapers became viable, even lucrative businesses. To attract the broadest possible audience for advertisers, newspapers dropped their highly partisan postures.

Into the 20th century, news outlets targeting minority readers were sometimes subjected to violence. So were labor reporters. However, as newspapers competed with each other for scoops, and as radio and TV news came on strong, the freedom of the press we think of today took shape. Court decisions no doubt cemented this culture, particularly the Supreme Court’s 1971 decision in the Pentagon Papers case. The press now had real institutional and agenda- setting power, the bedrock of which was objectivity, taste, and fairness.

Then the internet came along. For a while, media scholars saw this as a public good. Big corporations no longer had a monopoly on the free flow of information. New voices could be heard. But as the internet ate up the mainstream press, what emerged, historians and other scholars say, were volatile, partisan voices similar to the partisan press of Mark Twain’s time. Partisan outlets have become as dominant as the objective mainstream outlets of yore, if not more so. “The ability of the press to set the public agenda”—publishing nuanced, non-inflammatory content—“has become hacked,” Nerone says. And not just by partisan US outlets. Foreign powers, like Russia, have found a way into the conversation with fake, inflammatory news posted to social networks. The president himself has referred to reporters as “enemies of the state.”

Let’s remember what happened last May in Montana. Greg Gianforte, the Republican then running for the House of Representatives, was confronted by a Guardian US reporter with tough questions about health care. The topic isn’t slavery, yet as divisiveness goes, it’s just about the most controversial subject in the United States. In what realm is Gianforte’s response—to body-slam the reporter—even remotely expected? In Waddy Thompson’s day, perhaps. But if history truly does repeat itself, if the conditions of discourse in the United States appear even remotely similar to Thompson’s day, then maybe Gianforte’s response isn’t shocking after all. A commenter on the Washington Post article describing the body slam wrote this: “Journalists who don’t toe the party line need to get punished.”

ICYMI: One question that turns courageous journalists into cowards

“I am shot!”

By Michael Rosenwald

In 1883, with Twitter not yet a viable option for settling scores, the editors of two Richmond newspapers met in an open field to resolve their differences by shooting at each other.

Though duels were the gold standard in those days for defending one’s honor, rival journalists typically never went that far, settling for a bop on the nose or a brick through a window.

But those options weren’t appropriate for the level of animus between Richard F. Beirne, the editor of the Richmond State, and William C. Elan, editor of the Richmond Whig.

Abraham Lincoln had freed the slaves, but civil rights still vexed the country. Newspapers took sides. Long story short: Beirne thought Elan’s support of blacks in his paper’s editorials was not genuine. The Whig’s retort: “We laugh at the State’s vituperation and vaporing, and beg to remark that not only does the State lie, but its editor and owner lies.”

Fighting words.

Beirne, as The New York Times later reported, “demanded satisfaction” from Elan, putting him on notice for a duel. Representatives for the editors cordially made the arrangements, even agreeing that Elan’s nearsightedness made it necessary to shorten the standard 10 paces to eight.

“The weapons chosen were navy six-shooters,” writes Ryan Chamberlain in Pistols, Politics and the Press, “the largest of their kind.”

The confrontation came as duels were on their way out. Virginia had recently prohibited them. A detective got wind of the plans and showed up at the appointed time on his horse, arresting Beirne. Elan got away.

Both men remained committed to the idea of a shooting each other. The Times, for its part, stoked interest, covering the impending duel as if it were a prize fight.

“The excitement over the expected duel between Beirne and Elan has not abated,” the paper said. “All day anxious inquiries have been made as to where the principals are.”

Chamberlain, in his history of violence in journalism’s early days, writes that with papers on opposite sides of the civil rights question, “the sensational and national coverage of the rival editors started to have broader political implications.

“The duelists began to represent more than their personal quarrel,” he continues. “Because each editor was a strong advocate for his own political party, they began to symbolize opposing political ideals.”

Who might be maimed, however, was still of paramount interest to readers.

Finally, after using coded messages, the editors agreed to meet in West Virginia, where dueling was still legal.

“Neither had met before that day as they stared at one another from across their marks,” Chamberlain writes. “Both editors gripped their pistols and stared at each other in preparation for the first shot.”

They fired.

They missed.

The terms of the duel called for a second round.

They fired.

This time, Beirne stood tall.

Elan staggered, then fell to the ground, declaring the obvious: “I am shot!”

He had been hit in the leg. The wound, even in those days, wasn’t enough to kill him. While a doctor examined him, Elan smoked a cigar.

“Beirne declared that he was satisfied,” Chamberlain writes, “tipped his hat to Elan and left in a carriage.”

Michael Rosenwald is a reporter at the Washington Post. He has also written for The New Yorker, Esquire, and The Economist. Follow him on Twitter @mikerosenwald.