This AlterNet piece finds some revealing quotes from the Business Roundtable that show how that influential group’s views on who business is supposed to serve shifted after the shareholder revolution (and the Reagan revolution). Here’s what it said in 1981:

Balancing the shareholder’s expectations of maximum return against other priorities is one of the fundamental problems confronting corporate management. The shareholders must receive a good return but the legitimate concerns of other constituencies also must have appropriate attention. Striking the appropriate balance, some leading managers have come to believe that the primary role of corporations is to help meet society’s legitimate needs for goods and services and to earn a reasonable return for the shareholders in the process. They are aware that this must be done in a socially acceptable manner. They believe that by giving enlightened consideration to balancing the legitimate claims of all its constituents, a corporation will best serve the interest of the shareholders.

And 1997:

“In the Business Roundtable’s view, the paramount duty of management and of boards of directors is to the corporation’s stockholders; the interests of other stakeholders are relevant as a derivative of the duty to stockholders. The notion that the board must somehow balance the interests of stockholders against the interests of other stakeholders fundamentally misconstrues the role of directors.”

The article doesn’t really show what it says it will show—that corporations by law and precedent don’t have an obligation to put “shareholder profits over all else”—but I’d like to read a fuller exploration of that topic.

— And here’s another AlterNet article, from the same series on corporate America, in which a UMass professor argues that the shareholder revolution is to blame for a good deal of our economic woes:

In the name of this misguided philosophy, major U.S. corporations now channel virtually all of their profits to shareholders, not only in the form of dividends, which reward them for holding shares, but even more importantly in the form of stock buybacks, which reward them for selling shares. The sole purpose of stock buybacks is to give a manipulative boost to a company’s stock price. The top executives then benefit when they exercise their typically bountiful stock options and cash in by selling the stock. For 2001-2010, 459 companies in the S&P 500 Index in January 2011 distributed $1.9 trillion in dividends, equivalent to 40 percent of their combined net income, and $2.6 trillion in buybacks, equal to another 54 percent of their net income. After all that, what was left over for investments in innovation, including upgrading the capabilities of their workforces? Not much.

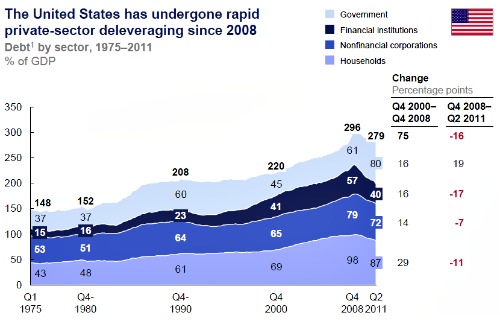

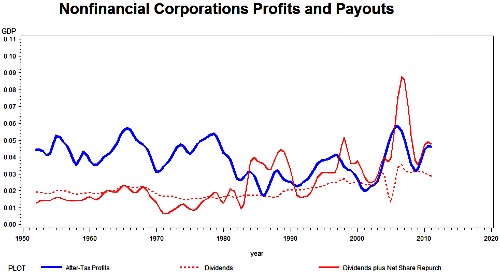

— That reminds me of JW Mason’s post at The Slack Wire, “Disgorge the Cash!” Mason writes that since 1980, public companies have given more than 100 percent of their profits to shareholders rather than reinvesting them into their companies. They could pay more than all of their profits because they levered up, I’d presume. Here’s a McKinsey chart showing that:

Here’s Mason:

Ryan Chittum is a former Wall Street Journal reporter, and deputy editor of The Audit, CJR’s business section. If you see notable business journalism, give him a heads-up at rc2538@columbia.edu. Follow him on Twitter at @ryanchittum.In the pre-neoliberal era, up until 1980 or so, nonfinancial businesses paid out about 40 percent of their profits to shareholders. But in most of the years since 1980, they’ve paid out more than all of them. In 2006, for example, nonfinancial corporations had after-tax earnings of $800 billion, and paid out $365 billion in dividends and $565 in net stock repurchases. In 2007, earnings were $750 billion, dividends were $480 billion, and net stock repurchases were $790 billion. (Yes, net stock repurchases exceeded after-tax profits.) In 2008 it was $600, $470, and $340 billion. And so on.

It was a common trope in accounts of the housing bubble that greedy or shortsighted homeowners were extracting equity from their houses with second mortgages or cash-out refinancings to pay for extra consumption. What nobody mentioned was that the rentier class had been doing this longer, and on a much larger scale, to the country’s productive enterprises. At the top of every boom in the neoliberal era, there’s been a massive round of stock buybacks, which you could think of as shareholders cashing out their bubble wealth. It’s a bit like the homeowners “using their houses as ATMs” during the 2000s. The difference, of course, is that if you took too much equity out of your house in the bubble, you’re the one stuck with the mortgage payments today. Whereas when shareholders use businesses as ATMs, those businesses’ workers and customers get to share the pain.