You can tell right from the headline on this Bloomberg News story that the piece is going to be seriously problematic:

Lamb for 12 on $400 Monthly Shows South Africa Welfare Addiction

Is this news story really going to suggest that a family of 12 is living high on the hog off what comes to $1.14 a month day per person? Yes, it is. Those good-for-nothing poor people and their lamb and macaroni. Let them eat veal!

Let’s pick it up from the second paragraph:

Side dishes: macaroni and bolognese sauce. What pays for the meal: South Africa’s taxpayers, via 4,540 rand ($418) in monthly government benefits. Nine of the residents in the house, from Matthys’s baby great-granddaughter to Hendrik, her husband, receive one kind of aid or another. Only one of the 12 works.

Welfare dependency, a problem across the developed world, has reached a danger level in South Africa. More people receive aid than have jobs, and the ratio has been worsening for five years. While the handouts have helped address abject poverty since the end of the apartheid regime, they haven’t helped recipients get skills needed for jobs in a country with 24 percent unemployment.

Did the ghosts of Lee Atwater and Ronald Reagan write this thing? It has everything but the Cadillac and the “strapping young buck.” Perhaps lamb is Afrikaans for “T-bone.”

Bloomberg writes that “only one of the 12 works.” But it never gets around to telling us that nine of the 12 aren’t of working age. We have to back into that ourselves. The heads of the household are in their 70s. There are seven kids. Bloomberg makes hay out of the fact that one, Christoline, says she’d have to move to Cape Town, 540 kilometers away, to look for a job if she didn’t get welfare for her baby. Christoline is 16, by the way.

That leaves two layabouts living on “handouts.” Is that because they’re lazy or because the unemployment rate in their city is some 90 percent?

That’s the first of a number of chicken-and-egg problems with Bloomberg’s piece. Here’s another:

In towns such as Brandvlei, dependence on social grants helps feed alcohol dependence, said Christolene Markus, a community-development worker at the Department of Social Services, as she stood in the door of the satellite office building. Two doors away is B&B Liquor Store, the biggest such establishment in town. People line up before 8 a.m. on Mondays.

“Look outside,” she said, pointing to a group of rowdy young men stumbling along the street running toward the store. “This is what it looks like when they get paid. And then later they come and beg at our office again.”

It blames welfare payments for fueling alcoholism, but doesn’t acknowledge that no-hope joblessness is surely a much bigger factor. It also implies that welfare payments for incentivizing pregnancy, but doesn’t acknowledge that poverty and pregnancy go hand in hand.

This isn’t to say welfare doesn’t provide negative incentives in some cases. It can and does, and there are legitimate reasons to restructure programs to less those effects. But at a minimum, it is highly questionable that welfare itself is a bigger factor in self-defeating behavior than the underlying poverty and joblessness it is meant to ameliorate. And a look at the data seriously undermines Bloomberg’s unsupported inferences.

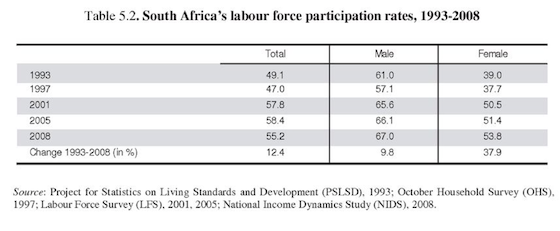

If welfare were really causing indolence in South Africa, you’d expect to see people dropping out of the labor force. But the OECD reports that labor participation has risen significantly over the last two decades, particularly among women, who are more likely to be welfare recipients (though it’s fallen sharply since the crisis, as it has just about everywhere):

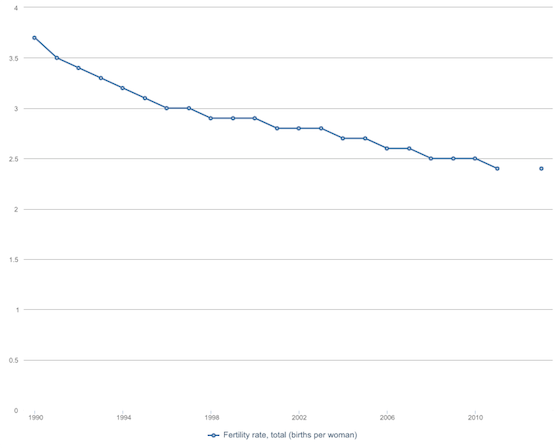

What about welfare-fueled pregnancies? Bloomberg, of all places, should know better than to rely on anecdotal data. With the explosion in welfare recipients in South Africa, you’d expect to see a booming birth rate, according to the wire’s logic. Instead, it has collapsed:

Does receiving welfare payments cause South Africans to work less? There’s data that actually contradict that via Katherine Eyal and Ingrid Woolard in Oxford’s Journal of African Economies:

We find that grant receipt is associated with a higher probability of being (in) the labour force, lower unemployment probability for those who do participate, and a higher probability of being employed. These effects are not small, ranging as high as 15% for some groups.

How’s the South African economy doing? Pretty good, all things considered. And by all things, I’m mainly talking about an HIV crisis that still plagues it, the lingering effects of the global financial crisis as well as the economic transformation that has accompanied the end of institutionalized segregation and political oppression not so long ago.

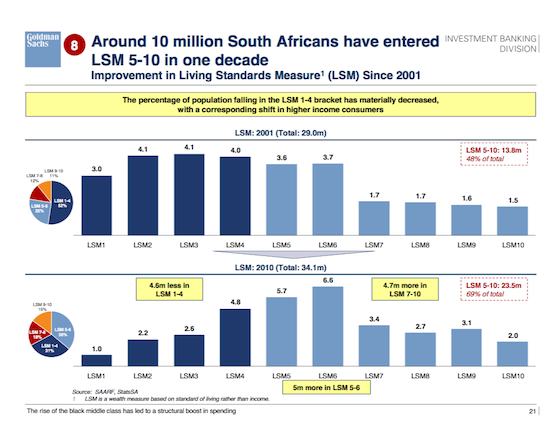

Government debt is still just 42 percent of GDP, up from a mere 28 percent before the crisis. South Africa’s stock market is worth more than $800 billion, ten times that of the next richest African country and 100 times more liquid in terms of trading volume. Real GDP per capita is up 40 percent since 1995. Disposable income has risen 10.3 percent a year since 2001. Productivity per worker has tripled in a decade. Extreme poverty has fallen dramatically, while the black poverty rate declined from 70 percent in 1993 to 61 percent in 2008. There’s been a dramatic upgrade in living standards across the population since 2001:

That chart and all the stats above come not from some goo-goo NGO, but from Goldman Sachs, which counts the growth in welfare grants from 2.4 million at the end of apartheid to 16.1 million now as one of the country’s “key advances” in “Two Decades of Freedom.” Those notorious Goldman lefties!

But can South Africa afford to give its poorest people lamb and macaroni on occasion? Bloomberg’s own reporting undermines its thesis:

Dependence on welfare has soared since South Africa’s first multiracial vote in 1994. At 13 percent of gross domestic product, spending on social programs including health but not education is less than the developed-world average, calculated by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development at 22 percent.

It reports that social spending in the country is 12 percent of government spending. Not 12 percent of GDP, but 12 percent of government spending, or about $12.4 billion. The South African economy is $392 billion. So welfare payments, which bring millions out of abject poverty, cost roughly 3.2 percent of GDP.

That includes old-age welfare, a la our Social Security.

Plus, South Africa is still one of the most unequal countries in the world—basically a third-world and first-world economy in the same country—which is why the headline fact here, that “16.5 million people receive government benefits, compared with 15.2 million working as of the fourth quarter of 2013” isn’t as relevant as an indicator of sustainability as spending levels are. Since high-income South Africans make so much more than those with low or no income, the taxes of the former can cover many of the latter. South Africa has relatively low taxes—roughly the same level as the US.

Then there are the massive structural issues that still weigh on the country’s primarily black population after apartheid, which Bloomberg all but ignores.

T.O. Molefe Melefe, writing at Africa Is a Country, is elegant on this, responding to Bloomberg’s anecdote about Christoline, the welfare recipient

But don’t mistake the desperate situation taking away the social grants would create for her as just the thing she, and her family, need to get jobs. If you know and understand the country’s history of racist land dispossessions and forced removals, and the destructive social effects of the migratory labor system on the communities supplying workers to the country’s economic centres like Cape Town and Johannesburg, you’ll know that it is a good and just thing that the social grants are stopping Christoline from leaving behind her one-year-old baby, family support network, and the possibility of returning to school in order to chase the faint promise of a job hundreds of miles away.

Melefe also picks up on the Reaganesque overtones of the piece.

Bloomberg, by the way, quotes no one that doesn’t criticize the welfare system. It’s a poorly done news story, frankly, and well below Bloomberg’s own standards.

One question I had that’s unanswered in the story: Did the Matthys family make this feast because a well-paid journalist from an important news organization was coming for a visit?

Ryan Chittum is a former Wall Street Journal reporter, and deputy editor of The Audit, CJR’s business section. If you see notable business journalism, give him a heads-up at rc2538@columbia.edu. Follow him on Twitter at @ryanchittum.