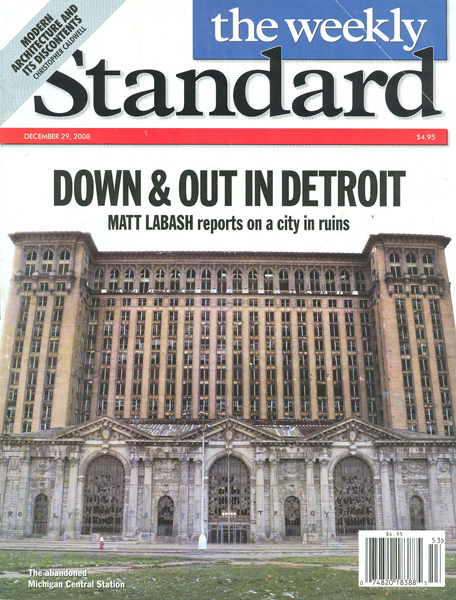

An Audit Credit to The Weekly Standard for helping to fill one of the business press’s yawning reality gaps: the space between “Detroit,” the metaphor, and Detroit, Michigan.

In a recent cover story titled “Down & Out in Detroit,” The Weekly Standard brilliantly, painstakingly, sometimes hilariously explores the city’s crumbling infrastructure, neighborhoods and institutions, and introduces us to some of its angry, struggling, stoic and resilient residents. This sprawling piece leaves no doubt about the reality of life in Detroit and leaves readers better off for having stumbled upon it.

Moving against the media traffic, the Standard reminds us that Detroit is a city first and a metaphor for the U.S. auto industry second. For the mainstream business press, Detroit is a metaphor first and last. Business coverage is all about “Detroit,” almost never about the city, which is what a hollowed-out economy like ours looks like in extremis.

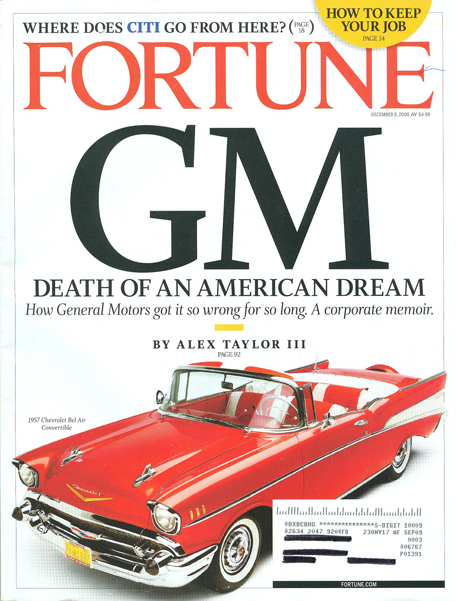

For a graphic demonstration on the differing perspectives on “Detroit,” note how the Standard cover contrasts with two related cover stories from about the same time.

First, The Weekly Standard:

Then Fortune:

And Time:

Fortune and Time took the standard approach. And if you search the past several months of news coverage for the word “Detroit,” once you exclude the Tigers, Lions and Red Wings, you will primarily find articles on the car industry and its tribulations.

That “Detroit” has become a metaphor is neither surprising nor inherently problematic. But that said, there is a problem here: that the national press has allowed the metaphor not just to enlarge reality—which is the point of metaphors—but to substitute for it. Detroit the city becomes a shadow, an afterthought, a non-thought, really, creating a key instance of that “reality gap” we mentioned above.

And this gap is a shame, because if the press told us in detail how “Detroit” and Detroit are interconnected—the ways in which American industrial and economic policy shape and reshape our cities—we would know a lot more than we do about our current predicament.

After all, the financial crisis comes after a long and painful period of globalization, deindustrialization, and financialization, one result of which has been a poisonous wage stagnation for the middle class, even as it has relentlessly increased its productivity.

Once a cradle of the middle class and a bastion of industrial productivity, Detroit is now a primary example of the unraveling of both, a nexus of failed economic policy. It is, alas, a gift to journalists trying to understand how we got here from there. It is, for all of its neglect—and even, to some extent, because of that neglect—an important place.

Thus a cheer for the Standard’s Matt Labash for getting on an airplane, for wandering around Detroit, for telling us with clear eyes and at great length what he saw. So simple and yet so rare!

The piece owes much of its impact, energy and even humor to the author’s skillful channeling of Detroit-area native and former New York Times reporter Charlie LeDuff. Labash’s introduction to LeDuff is so good, we’ll give it to you whole cloth:

For many, Detroit is identified with cars or soul music, with the novels of Elmore Leonard or the architecture of Albert Kahn. If they really hate Detroit, they might recall that its suburbs coughed up Madonna. But for me, Detroit has become synonymous with one man: Charlie LeDuff.

Currently a metro reporter at the Detroit News, Charlie crossed my path in 2003 when he was a hotshot national correspondent for the New York Times. Stuck on a press bus trailing Arnold Schwarzenegger in the last days before the recall election, I spied a madman a few rows ahead banging on the window as a jubilant crowd in Bakersfield mistook ours for the candidate’s bus. Pounding away, Charlie fed back their mistaken adulation. ‘I’M THE MEDIA! YOU LOVE THE MEDIA!’ he bellowed.

I errantly asked someone what motorcycle magazine he worked for, thinking him an out-of-work biker/pirate since he looked like the bastard spawn of Sonny Barger and Jean Lafitte—I described him at the time as ‘a leathered scribe with bandito facial hair.’ Part Cajun, part Native-American (he says his Indian name is ‘White Boy’), Charlie was as much performer as reporter, walking around in sleeveless New York Post baseball jerseys, once breaking a wine glass on his head to keep campaign staffers off balance. ‘It’s a trick,’ he told me quietly, ‘the glass is thin up at the top.’

But Charlie was also writing some of the best newspaper feature stories in the country. His beat involved covering what he calls ‘the hole,’ forgotten people in forgotten places.

LeDuff comes across as an ideal guide to Detroit: energetic, committed and deeply sane, despite occasional appearances to the contrary. Also, crucially, he is an experienced, Pulitzer Prize-winning national reporter who chose to return home. Thus, he combines breadth of experience not just with local familiarity, but with local allegiance. Which is to say, with the kind of attachment that can only be bred in the bone.

How did LeDuff end up leaving the Times for Detroit? Labash tells us that

earlier this year, as the nation was roiling and the Detroitification of America was set to explode with the mortgage crisis and massive layoffs, Charlie moved home to work for the Detroit News. ‘I chose them because they chose me… They let me do human,’ he says. At first, I felt sorry for him. After all, who goes back to Detroit willingly to find work these days? There was a notes-from-Siberia feel to the whole enterprise. When I talked to Charlie on the phone, passing on an idle bit of media gossip, then insisting it stay in the cone of silence, he’d say, ‘Who am I going to tell, Matt? I’m in Detroit.’

But I stopped feeling sorry for him when his pieces started arriving in my inbox like a steady drip. Charlie was back in ‘the hole’ with a vengeance.

Nice.

In fact, the Standard piece is as much about urban journalism as it is about the city itself. Listen to LeDuff here:

One night over dinner, Charlie admits that he knows most people think he’s gone back to a dying newspaper in a dying town. But he feels he has work to do here. Not the kind of work that makes Gawker. Real work. He’s always wanted to write about ‘my people,’ as he calls them—Detroiters in the hole—but he wasn’t ready before. Now he is.

The conversation continues:

He says there has to be room for the kind of journalism ‘where it’s not a fetish, where it’s not blaxploitation, where you are actually a human being with a point of view. The city is full of good people, living next to s—.’ But most media-types don’t bother to ask since they view those people as ‘dumb, uneducated, toothless rednecks. They’re ghetto-dwelling blacks. Right? They’re poor Mexicans.

They’re a concept, not a people.’

At this point you may be wondering whether you shouldn’t just read LeDuff. And you should—try this or this for starters—but stick with Labash too. He demonstrates a sharp eye and keen empathy as he hangs around with LeDuff and friends, and then branches out on his own.

In fact, you are in for a long ride. The article goes on for seventeen pages. But, impressively, it is never boring. We give credit not just to Labash for that but also to the Standard, for providing the space and allowing for so many photos. More than 10,000 words unscroll around excellent photographs, several by local photographer and artist Randy Wilcox. Wilcox, as Labash puts it, “combs the ruins of Detroit.” And out of these ruins come photos like:

and

Labash writes, “I come to think of Wilcox as the curator of a museum that’s been overturned and looted.” And Labash’s own impression of Detroit, a crushing place that still manages to contain “pockets of grace,” complements Wilcox’s:

In my line of work, I’ve seen plenty of inner cities, but I’ve never seen anything in a non-Third World country like the east side of Detroit. Maybe the 9th Ward of New Orleans after Katrina. But New Orleans had the storm as an excuse. Here, the storm has been raging for 50 years, starting with the closing of the hulking Albert Kahn-designed Packard Plant in 1956, which a half century later, still stands like a disgraced monument to lost grandeur.

Here is Wilcox’s photo of that plant now:

For a comparison, take a look at a Library of Congress photo of that same building in the early years of the Twentieth Century, which we found in the Library of Congress catalogue (Labash’s piece is the kind that inspires you to troll the library’s superb American Memory collection):

(Credit: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection)

We are, unfortunately, used to seeing images of our cities in ruins, but such a contrast should shock us. How has it come to this? Not just the state of Detroit, that is, but our complacency about it?

But we are getting ahead of ourselves. The best way to start thinking about these questions is to start looking at the facts on the ground. So back to Labash’s Detroit.

Some of Labash’s most interesting anecdotes come from his time spent with a group of local firefighters, who witness the daily struggles of Detroit residents. They respond to calls of domestic disturbances when underfunded police don’t. They fight fire after fire, wearing damaged protective gear. They don’t have a fire pole, because the city sold it. They get their cars stolen—even while attending the funeral of a colleague who died on the job.

But the firefighters admirably live up to what we will blandly call challenges, acting as lynchpins for the community. And their empathy is truly moving:

[Firefighter Mike] Nevin told me they recently fought a fire resulting from a man illegally siphoning gas with a rubber hose. He blew up an entire block. ‘They had kids in the street, glass sticking out of their head,’ he says. But, as horrible as it was, he says, ‘The guy’s got four kids. And there’s no jobs. And you know, he’s got to keep the kids warm. So they come out, and they cut the gas off. Everybody looks to dad. “Hey dad, I’m cold. Hey dad, I’m hungry.” It breaks your f—ing heart, man. You’re dad. You’re superman. So what do you do? “I’ve got to pull something by hook or crook, man.” You know, it’s like everybody is just trying to get by right now.’

These are the people who could use some help. And yet:

‘Hear the sirens?’ Nevin asks. ‘Someone is going to a fire. That’s all day long. This is a city where the sirens never stop.’

This place, he says, ‘It’s like a forgotten secret. It’s like a lost city. And they never really talk about the f—ing truth about what is going on with this town.’

What makes this article so extraordinary is that Labash cares enough to give his subjects a sustained voice.

We suggest you read the rest of the piece, which is both devastating and deeply engrossing. But we do offer one important caveat. Labash confines his analysis of cause and effect to vague statements like, “Precisely what caused all this mess is perhaps best left to historians.” And, even allowing for a certain degree of poetic license, he veers further off course when he ends his piece with the suggestion that only God can save Detroit.

The fact is, while may factors have contributed to Detroit’s decline, it was not divinely inevitable and so anyone waiting around for God to save it should figure on waiting quite a while. For the ways in which government policy, as well as other very human actions, contributed to Detroit’s predicament, take a look at Thomas Sugrue’s excellent The Origins of the Urban Crisis.

Or, for a shorter version, take a look at this Washington Post piece from July 2007, by historian Kevin Boyle.

Furthermore, while Detroit has been particularly hard hit, these problems are by no means limited to that city, or even the Rust Belt more broadly. U.S. cities have long suffered from underfunding, and are forced to go to the federal government hat in hand just to get by. And in recent decades, government policies like deregulation and privatization, fervently although not exclusively embraced by the Right, have served to increase the income inequality that plays such an important role in the dissolution of our social fabric—urban and otherwise.

But we don’t want to turn this post into an analysis of the conservative Weekly Standard’s editorial stances. And in all fairness, Labash is hardly alone in lacking a framework for the story of Detroit. The press of all political persuasions has a hard time with it. And, unlike so much else that we came across on Detroit, what Labash does offer us is well worth the read.

Recent months did give us some, if not many, other examples of good national or international reporting on the city but, interestingly, they are almost all from European or Canadian newspapers. None of them drew us in quite as surely as Labash did. But The Irish Times had a notable piece. As did The Globe and Mail’s Report on Business (which also impressed us recently with reporting on Lehman Brothers). As did The Guardian. Like Labash, these writers see the effects of Detroit’s misfortune more clearly than its causes. But by going to the city, they all come back with some good material.

And what was everyone else doing? By and large, run-of-the-mill stories on “Detroit,” where the real Detroit tended to make only cameo appearances at best. And even on the rare occasions when the city moved to center stage, reporting tends to read more like a postcard—Be glad you aren’t here!, Regards, The National Media—than a serious portrait.

And, quite frankly, by the time we get down to this, to critiquing recent stories that substantively address the reality of the city of Detroit, our pool has shrunk so far that we can count examples on our fingers. Far more typical is the Time cover story we showed you earlier, called “The Case for Saving Detroit,” where “Detroit” turns out to mean the auto industry.

If you want to read the real case for saving Detroit, no quotes, try The Weekly Standard.

Elinore Longobardi is a Fellow and staff writer of The Audit, the business-press section of Columbia Journalism Review.