Back in December, Peter Kafka summed up the most important question with regards to the future of online advertising. Do advertising dollars ultimately end up where people spend their time, he asked, echoing Kleiner Perkins’ Mary Meeker says, or, pace Bernstein Research’s Todd Juenger, is that a “fallacy”?

I’m with Juenger on this one. As he says, “time spent is supply, advertising spend is demand… Just because there is a large and growing supply of Internet inventory doesn’t mean advertisers have a correspondingly large desire to deliver more Internet impressions.” Indeed, as the price of online inventory continues to fall, it seems just as likely that online ad spend will go down (because the ads being bought are getting cheaper) as that it will go up.

According to Meeker, some 67% of all ad dollars are spent either on TV or in print. And according to Juenger, ad spend on TV actually went up, between 2009 and 2012, even as Americans’ attention moved away from TV and towards other screens. That makes sense to me, mainly because of the point I was making back in 2009, drawing the distinction between brand advertising, on the one hand, and direct marketing, on the other. TV is brand advertising; online ads, by contrast, are closer to direct marketing.

When people like Meeker look at ad spend, they’re looking mainly at brand advertising. Brands are valuable things, and billions of dollars are spent every year to keep them that way, mostly on TV and in print. And if you have a big national brand, there’s really only one way to reach a big national audience: you need to buy ads on TV. Doing so is expensive, but it’s necessary, and it works, which explains the huge sums of money which still flow into TV every year.

As Juenger explains, the audience for network TV has been shrinking by 1.8% per year for the past 20 years — but at the same time, the audience for every other TV channel has been “atomized into increasingly tinier fragments”, leaving the networks the only game in town for advertisers wanting scale. The result is that network-TV ads have been increasing in price by 4.9% per year on a per-person-reached basis, resulting in total revenues growing, by 3% a year, in a market which is actually shrinking.

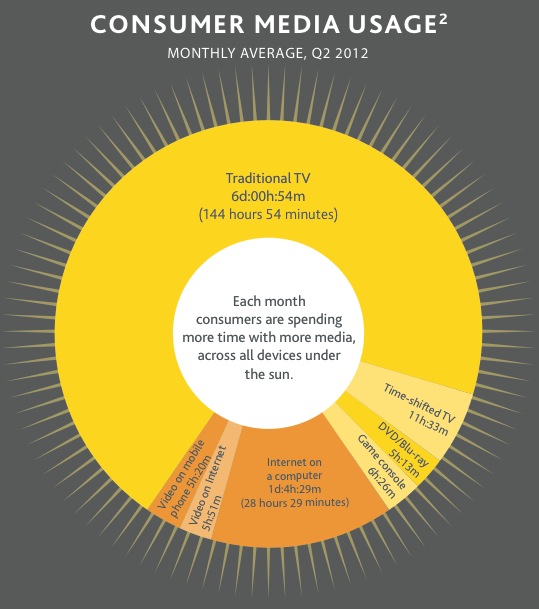

The corollary to the continued success of network TV is the utter irrelevance of online ads. Here’s a handy chart from Nielsen, breaking down the amount of time we spend in front of various screens each month:

TV is still the monster, the elephant: for all the talk of cord-cutting, Americans have clearly voted that, given the choice, they’d much rather have cable TV than broadband internet.

And for web-based publishers, the situation is much, much worse even than this chart makes it look. Consider: the number of websites out there is many orders of magnitude greater than the number of TV channels, which means that even as network TV is winning over small cable channels, small cable channels are still in a much better position than just about any website which isn’t called Facebook or Google or Yahoo. Moreover, if you’re running a news site, you’ll be even more sobered to learn that just 2.7% of the time that people spend on the internet is spent on news sites. You think you’re competing against a lot of other news sites to attract advertisers? You don’t know the half of it. In reality, you’re competing against the other 97.3% of websites, and they are competing against TV. It’s a fight you can’t hope to win, especially since non-news websites are so much better at delivering people primed to buy stuff (search) or delivering large numbers of people in narrowly-targeted demographics (Facebook).

The key concept at the heart of Juenger’s fallacy — the thing which Meeker doesn’t seem to understand — is the fact that internet advertising in no way substitutes for TV or print advertising, no matter how often digital ad-sales people bring out their metrics of comparative CPMs.

In 2011, I gave a talk to a group of online ad-sales people who were so full of the multitude of different ways that they could target and quantify their product, they literally no longer understood what brand advertising is, or why it exists, or why brands would be so foolish as to spend so much money on it. They’re quants, living in a world where something only has value insofar as it can be quantified, and where the unquantifiable therefore is perceived to have no value at all. In other words, they’re basically in the direct-marketing business: they’re the digital version of junk mail. As a result, just about every website in the world is in the business of delivering that digital junk mail to our computers and iPhones and iPads.

This, then, is the biggest reason why TV ad dollars are not going to become online ad dollars: online ads simply don’t do what TV ads do. TV ads are large and beautifully produced and expensive, and they’re presented on a beautiful screen without distractions: they fill up the screen, and 30 seconds of time, and they appear often enough that they become part of the world of the people watching 145 hours of TV every month. Online ads don’t behave like that at all: they’re easy to ignore, there’s nothing inherently interesting about them, and insofar as they grab your attention, they tend to do so in a very annoying way, by preventing you from reading or watching the thing you were looking for.

Hence the rise of so-called native ads: things you want to read and look at and click on. There’s a certain amount of promise there, and the native-ad industry is certainly going to grow from its present size. But it’s tough: building these things is a huge amount of work for the advertiser, with no guaranteed payoff. And selling them is even more work for any publisher.

And here’s the next big problem with selling online advertising, especially native advertising: it’s really expensive to do so. While online journalism is still cheap, online ad-sales staffers tend to cost a fortune, especially if they have a clue what they’re doing. This is something the Meekers of the world would do well to remember: the ad dollars spent online are spread across so many sites that a massive proportion of them end up just going straight into the pockets of the people selling those units, or else to the various ad networks and other intermediaries which have popped up in a very busy and messy space.

This kind of thing just doesn’t exist in TV or even in brand advertising more generally — areas which are much simpler, much easier to navigate, and which sit much more comfortably within consumers’ comfort zone. And it’s not going away. I was told this evening that Buzzfeed alone has no fewer than sixty ad-sales people, all of whom are out there, knocking on doors, taking potential clients out to lunch, and generating income one hard-won deal at a time. That doesn’t scale.

Indeed, if you want to get your brand out there on the internet, you can try buying ads on websites, or you can try going native on a site like Buzzfeed, but the fact is that the whole point of the internet is that it disintermediates: it’s great at drawing direct connections. Hence the rise of what’s known as “content marketing”: why buy ad space from a publisher, when you can be the publisher instead? We’re still in the early days of this, but already musicians are discovering that brands are much friendlier — and pay much higher rates — than record labels, while American Express has been employing extremely good journalists for years.

On top of that, as Liz Gannes and Noah Brier note, nobody “goes online” any more: the internet is becoming an ambient background thing-that’s-always-there, rather than a mass communications medium that people consciously think of themselves as paying attention to. When you pick up a magazine, you do so because you want to read it; similarly, when you turn on the TV. But the internet is different: your phone is always just sitting there, and sometimes it beeps at you; your computer is always on your desk at work, and it’s never not online. In a mobile world, the distinction between being online and not being online is an increasingly silly one to draw. And as a result, the idea of using “time spent online” as a useful metric of anything, really, is equally silly.

So if the internet is not going to displace TV as a medium for mass-market brand advertising, might it at least be good at direct marketing? Can publishers not deliver certain readers, in certain demographics, to marketers who want to reach them? To a certain extent, yes. But the fact is that Google and Facebook, between them, are extremely good at delivering as many of those readers as any advertiser could ever want: all that Facebook needs to do is turn a dial, and billions of new impressions get added to the stock of global inventory, targeted at any demographic that any advertiser could want. Google, similarly, owns search, especially mobile search. It’s conceivable that some marketers might prefer to reach an audience some other way — but this is a race to the bottom, with a finite amount of demand chasing an essentially infinite amount of supply. That’s a buyer’s world, where the sellers have no real leverage at all.

Some very large proportion of the websites on the internet have a pretty basic business model: “we will publish great content; millions of people will want to read or view that content; advertisers will want to reach those people; and so we’ll be able to sell our audience to advertisers and make lots of money”. There are people out there who have succeeded with that model, but the number of successes is dwarfed by the number of failures, and the amount of scale you need to even get your foot in any media buyer’s door has been rising dramatically for years. By the time you’ve paid for your content and for your ad-sales infrastructure, the chances that you’ll have any money at all left over for your shareholders are slim indeed, and getting slimmer year by year.

All of which means that smart online publishers are looking beyond advertising, to other forms of generating revenues. But that story will have to wait for part 2.

Felix Salmon is a financial writer, editor, and podcaster. A former finance blogger for Reuters and Condé Nast Portfolio, his work can be found at publications including Slate and Wired, as well as his own Substack newsletter.